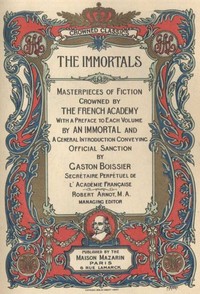

Read and listen to the book The Immortals: Masterpieces of Fiction, Crowned by the French Academy — Complete by Various.

Audiobook: The Immortals: Masterpieces of Fiction, Crowned by the French Academy — Complete by Various

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The French Immortals, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: The French Immortals

Author: Various

Release Date: October 30, 2004 [eBook #4000] [Most recently updated: December 17, 2022]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

Produced by: David Widger

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE FRENCH IMMORTALS ***

THE ENTIRE PROJECT GUTENBERG EDITION OF THE FRENCH IMMORTALS

CROWNED BY THE FRENCH ACADEMY

1905

CONTENTS

1. Serge Panine, by Georges Ohnet [see also #3918] 2. The Red Lily, by Anatole France [see also #3922] 3. Monsieur, Madame and Bebe by Gustave Droz [see also #3926] 4. Prince Zilah by Jules Claretie [see also #3930] 5. Zibeline by Phillipe de Masa [see also #3934] 6. A Woodland Queen, by Andre Theuriet [see also #3938] 7. Child of a Century, Alfred de Musset [see also #3942] 8. Monsieur de Camors by Octave Feuillet [see also #3946] 9. Cinq Mars, by Alfred de Vigny [see also #3953] 10. L'Abbe Constantin by Ludovic Halevy [see also #3957] 11. Romance of Youth by Francois Coppee [see also #3962] 12. Cosmopolis by Paul Bourget [see also #3967] 13. Jacqueline by Th. Bentzon (Mme. Blanc) [see also #3971] 14. The Ink-Stain by Rene Bazin [see also #3975] 15. Fromont and Risler, by Alphonse Daudet [see also #3980] 16. Gerfaut by Charles de Bernard [see also #3985] 17. Conscience by Hector Malot [see also #3990] 18. Madame Chrysantheme by Pierre Loti [see also #3995] 19. An "Attic" Philosopher by Emile Souvestre [see also #3999]

PG Editor's Note: March 4, 2009

All 19 individual volumes in this set have been corrected, reproofed and reposted with an accompanying html file.

An html file is also available for this complete volume with links to all individual volumes and the individual books and chapters.

This text below has not been reproofed and still has a few errors.

DW.

SERGE PANINE By GEORGES OHNET

With a General Introduction to the Series by GASTON BOISSIER, Secretaire Perpetuel de l'academie Francaise.

GENERAL INTRODUCTION

1905 BY ROBERT ARNOT

The editor-in-chief of the Maison Mazarin--a man of letters who cherishes an enthusiastic yet discriminating love for the literary and artistic glories of France--formed within the last two years the great project of collecting and presenting to the vast numbers of intelligent readers of whom New World boasts a series of those great and undying romances which, since 1784, have received the crown of merit awarded by the French Academy--that coveted assurance of immortality in letters and in art.

In the presentation of this serious enterprise for the criticism and official sanction of The Academy, 'en seance', was included a request that, if possible, the task of writing a preface to the series should be undertaken by me. Official sanction having been bestowed upon the plan, I, as the accredited officer of the French Academy, convey to you its hearty appreciation, endorsement, and sympathy with a project so nobly artistic. It is also my duty, privilege, and pleasure to point out, at the request of my brethren, the peculiar importance and lasting value of this series to all who would know the inner life of a people whose greatness no turns of fortune have been able to diminish.

In the last hundred years France has experienced the most terrible vicissitudes, but, vanquished or victorious, triumphant or abased, never has she lost her peculiar gift of attracting the curiosity of the world. She interests every living being, and even those who do not love her desire to know her. To this peculiar attraction which radiates from her, artists and men of letters can well bear witness, since it is to literature and to the arts, before all, that France owes such living and lasting power. In every quarter of the civilized world there are distinguished writers, painters, and eminent musicians, but in France they exist in greater numbers than elsewhere. Moreover, it is universally conceded that French writers and artists have this particular and praiseworthy quality: they are most accessible to people of other countries. Without losing their national characteristics, they possess the happy gift of universality. To speak of letters alone: the books that Frenchmen write are read, translated, dramatized, and imitated everywhere; so it is not strange that these books give to foreigners a desire for a nearer and more intimate acquaintance with France.

Men preserve an almost innate habit of resorting to Paris from almost every quarter of the globe. For many years American visitors have been more numerous than others, although the journey from the United States is long and costly. But I am sure that when for the first time they see Paris--its palaces, its churches, its museums--and visit Versailles, Fontainebleau, and Chantilly, they do not regret the travail they have undergone. Meanwhile, however, I ask myself whether such sightseeing is all that, in coming hither, they wish to accomplish. Intelligent travellers--and, as a rule, it is the intelligent class that feels the need of the educative influence of travel--look at our beautiful monuments, wander through the streets and squares among the crowds that fill them, and, observing them, I ask myself again: Do not such people desire to study at closer range these persons who elbow them as they pass; do they not wish to enter the houses of which they see but the facades; do they not wish to know how Parisians live and speak and act by their firesides? But time, alas! is lacking for the formation of those intimate friendships which would bring this knowledge within their grasp. French homes are rarely open to birds of passage, and visitors leave us with regret that they have not been able to see more than the surface of our civilization or to recognize by experience the note of our inner home life.

How, then, shall this void be filled? Speaking in the first person, the simplest means appears to be to study those whose profession it is to describe the society of the time, and primarily, therefore, the works of dramatic writers, who are supposed to draw a faithful picture of it. So we go to the theatre, and usually derive keen pleasure therefrom. But is pleasure all that we expect to find? What we should look for above everything in a comedy or a drama is a representation, exact as possible, of the manners and characters of the dramatis persona of the play; and perhaps the conditions under which the play was written do not allow such representation. The exact and studied portrayal of a character demands from the author long preparation, and cannot be accomplished in a few hours. From, the first scene to the last, each tale must be posed in the author's mind exactly as it will be proved to be at the end. It is the author's aim and mission to place completely before his audience the souls of the "agonists" laying bare the complications of motive, and throwing into relief the delicate shades of motive that sway them. Often, too, the play is produced before a numerous audience--an audience often distrait, always pressed for time, and impatient of the least delay. Again, the public in general require that they shall be able to understand without difficulty, and at first thought, the characters the author seeks to present, making it necessary that these characters be depicted from their most salient sides--which are too often vulgar and unattractive.

In our comedies and dramas it is not the individual that is drawn, but the type. Where the individual alone is real, the type is a myth of the imagination--a pure invention. And invention is the mainspring of the theatre, which rests purely upon illusion, and does not please us unless it begins by deceiving us.

I believe, then, that if one seeks to know the world exactly as it is, the theatre does not furnish the means whereby one can pursue the study. A far better opportunity for knowing the private life of a people is available through the medium of its great novels. The novelist deals with each person as an individual. He speaks to his reader at an hour when the mind is disengaged from worldly affairs, and he can add without restraint every detail that seems needful to him to complete the rounding of his story. He can return at will, should he choose, to the source of the plot he is unfolding, in order that his reader may better understand him; he can emphasize and dwell upon those details which an audience in a theatre will not allow.

The reader, being at leisure, feels no impatience, for he knows that he can at any time lay down or take up the book. It is the consciousness of this privilege that gives him patience, should he encounter a dull page here or there. He may hasten or delay his reading, according to the interest he takes in his romance-nay, more, he can return to the earlier pages, should he need to do so, for a better comprehension of some obscure point. In proportion as he is attracted and interested by the romance, and also in the degree of concentration with which he reads it, does he grasp better the subtleties of the narrative. No shade of character drawing escapes him. He realizes, with keener appreciation, the most delicate of human moods, and the novelist is not compelled to introduce the characters to him, one by one, distinguishing them only by the most general characteristics, but can describe each of those little individual idiosyncrasies that contribute to the sum total of a living personality.

When I add that the dramatic author is always to a certain extent a slave to the public, and must ever seek to please the passing taste of his time, it will be recognized that he is often, alas! compelled to sacrifice his artistic leanings to popular caprice-that is, if he has the natural desire that his generation should applaud him.

As a rule, with the theatre-going masses, one person follows the fads or fancies of others, and individual judgments are too apt to be irresistibly swayed by current opinion. But the novelist, entirely independent of his reader, is not compelled to conform himself to the opinion of any person, or to submit to his caprices. He is absolutely free to picture society as he sees it, and we therefore can have more confidence in his descriptions of the customs and characters of the day.

It is precisely this view of the case that the editor of the series has taken, and herein is the raison d'etre of this collection of great French romances. The choice was not easy to make. That form of literature called the romance abounds with us. France has always loved it, for French writers exhibit a curiosity--and I may say an indiscretion--that is almost charming in the study of customs and morals at large; a quality that induces them to talk freely of themselves and of their neighbors, and to set forth fearlessly both the good and the bad in human nature. In this fascinating phase of literature, France never has produced greater examples than of late years.

In the collection here presented to American readers will be found those works especially which reveal the intimate side of French social life-works in which are discussed the moral problems that affect most potently the life of the world at large. If inquiring spirits seek to learn the customs and manners of the France of any age, they must look for it among her crowned romances. They need go back no farther than Ludovic Halevy, who may be said to open the modern epoch. In the romantic school, on its historic side, Alfred de Vigny must be looked upon as supreme. De Musset and Anatole France may be taken as revealing authoritatively the moral philosophy of nineteenth-century thought. I must not omit to mention the Jacqueline of Th. Bentzon, and the "Attic" Philosopher of Emile Souvestre, nor the, great names of Loti, Claretie, Coppe, Bazin, Bourget, Malot, Droz, De Massa, and last, but not least, our French Dickens, Alphonse Daudet. I need not add more; the very names of these "Immortals" suffice to commend the series to readers in all countries.

One word in conclusion: America may rest assured that her students of international literature will find in this series of 'ouvrages couronnes' all that they may wish to know of France at her own fireside--a knowledge that too often escapes them, knowledge that embraces not only a faithful picture of contemporary life in the French provinces, but a living and exact description of French society in modern times. They may feel certain that when they have read these romances, they will have sounded the depths and penetrated into the hidden intimacies of France, not only as she is, but as she would be known.

GASTON BOISSIER SECRETAIRE PERPETUEL DE L'ACADEMIE FRANCAISE

GEORGES OHNET

The only French novelist whose books have a circulation approaching the works of Daudet and of Zola is Georges Ohnet, a writer whose popularity is as interesting as his stories, because it explains, though it does not excuse, the contempt the Goncourts had for the favor of the great French public, and also because it shows how the highest form of Romanticism still ferments beneath the varnish of Naturalism in what is called genius among the great masses of readers.

Georges Ohnet was born in Paris, April 3, 1848, the son of an architect. He was destined for the Bar, but was early attracted by journalism and literature. Being a lawyer it was not difficult for him to join the editorial staff of Le Pays, and later Le Constitutionnel. This was soon after the Franco-German War. His romances, since collected under the title 'Batailles de la Vie', appeared first in 'Le Figaro, L'Illustration, and Revue des Deux Mondes', and have been exceedingly well received by the public. This relates also to his dramas, some of his works meeting with a popular success rarely extended to any author. For some time Georges Ohnet did not find the same favor with the critics, who often attacked him with a passionate violence and unusual severity. True, a high philosophical flow of thoughts cannot be detected in his writings, but nevertheless it is certain that the characters and the subjects of which he treats are brilliantly sketched and clearly developed. They are likewise of perfect morality and honesty.

There was expected of him, however, an idea which was not quite realized. Appearing upon the literary stage at a period when Naturalism was triumphant, it was for a moment believed that he would restore Idealism in the manner of George Sand.

In any case the hostile critics have lost. For years public opinion has exalted him, and the reaction is the more significant when compared with the tremendous criticism launched against his early romances and novels.

A list of his works follows:

Serge Panine (1881), crowned by the French Academy, has since gone through one hundred and fifty French editions; Le Maitre des Forges (1882), a prodigious success, two hundred and fifty editions being printed (1900); La Comtesse Sarah (1882); Lise Fleuyon (1884); La Grande Maynieye (1886); Les Dames de Croix-Mort (1886); Volonte (1888); Le Docteur Rameau (1889); Deynier Amour (1889); Le Cure de Favieyes (1890); Dette de Haine (1891); Nemsod et Cie. (1892); Le Lendemain des Amours (1893); Le Droit de l'Enfant (1894.); Les Vielles Rancunes (1894); La Dame en Gris (1895); La Fille du Depute (1896); Le Roi de Paris (1898); Au Fond du Gouffre (1899); Gens de la Noce (1900); La Tenibreuse (1900); Le Cyasseur d'Affaires (1901); Le Crepuscule (1901); Le Marche a l'Amour (1902).

Ohnet's novels are collected under the titles, 'Noir et Rose (1887) and L'Ame de Pierre (1890).

The dramatic writings of Georges Ohnet, mostly taken from his novels, have greatly contributed to his reputation. Le Maitre des Forges was played for a full year (Gymnase, 1883); it was followed by Serge Panine (1884); La Comtesse Sarah (1887). La Grande Mayniere (1888), met also with a decided and prolonged success; Dernier Amour (Gymnase, 1890); Colonel Roquebrune (Porte St. Martin, 1897). Before that he had already written the plays Regina Sarpi (1875) and Marthe (1877), which yet hold a prominent place upon the French stage.

I have shown in this rapid sketch that a man of the stamp of Georges Ohnet must have immortal qualities in himself, even though flayed and roasted alive by the critics. He is most assuredly an artist in form, is endowed with a brilliant style, and has been named "L'Historiographe de la bourgeoise contemporaine." Indeed, antagonism to plutocracy and hatred of aristocracy are the fundamental theses in almost every one of his books.

His exposition, I repeat, is startlingly neat, the development of his plots absolutely logical, and the world has acclaimed his ingenuity in dramatic construction. He is truly, and in all senses, of the Ages.

VICTOR CHERBOULIEZ de l'Academie Francaise

SERGE PANINE

BOOK 1.

CHAPTER I

THE HOUSE OF DESVARENNES

The firm of Desvarennes has been in an ancient mansion in the Rue Saint Dominique since 1875; it is one of the best known and most important in French industry. The counting-houses are in the wings of the building looking upon the courtyard, which were occupied by the servants when the family whose coat-of-arms has been effaced from above the gate-way were still owners of the estate.

Madame Desvarennes inhabits the mansion which she has had magnificently renovated. A formidable rival of the Darblays, the great millers of France, the firm of Desvarennes is a commercial and political power. Inquire in Paris about its solvency, and you will be told that you may safely advance twenty millions of francs on the signature of the head of the firm. And this head is a woman.

This woman is remarkable. Gifted with keen understanding and a firm will, she had in former times vowed to make a large fortune, and she has kept her word.

She was the daughter of a humble packer of the Rue Neuve-Coquenard. Toward 1848 she married Michel Desvarennes, who was then a journeyman baker in a large shop in the Chaussee d'Antin. With the thousand francs which the packer managed to give his daughter by way of dowry, the young couple boldly took a shop and started a little bakery business. The husband kneaded and baked the bread, and the young wife, seated at the counter, kept watch over the till. Neither on Sundays nor on holidays was the shop shut.

Through the window, between two pyramids of pink and blue packets of biscuits, one could always catch sight of the serious-looking Madame Desvarennes, knitting woollen stockings for her husband while waiting for customers. With her prominent forehead, and her eyes always bent on her work, this woman appeared the living image of perseverance.

At the end of five years of incessant work, and possessing twenty thousand francs, saved sou by sou, the Desvarennes left the slopes of Montmartre, and moved to the centre of Paris. They were ambitious and full of confidence. They set up in the Rue Vivienne, in a shop resplendent with gilding and ornamented with looking-glasses. The ceiling was painted in panels with bright hued pictures that caught the eyes of the passers-by. The window-shelves were of white marble, and the counter, where Madame Desvarennes was still enthroned, was of a width worthy of the receipts that were taken every day. Business increased daily; the Desvarennes continued to be hard and systematic workers. The class of customers alone had changed; they were more numerous and richer. The house had a specialty for making small rolls for the restaurants. Michel had learned from the Viennese bakers how to make those golden balls which tempt the most rebellious appetite, and which, when in an artistically folded damask napkin, set off a dinner-table.

About this time Madame Desvarennes, while calculating how much the millers must gain on the flour they sell to the bakers, resolved, in order to lessen expenses, to do without middlemen and grind her own corn. Michel, naturally timid, was frightened when his wife disclosed to him the simple project which she had formed. Accustomed to submit to the will of her whom he respectfully called "the mistress," and of whom he was but the head clerk, he dared not oppose her. But, a red-tapist by nature, and hating innovations, owing to weakness of mind, he trembled inwardly and cried in agony:

"Wife, you'll ruin us."

The mistress calmed the poor man's alarm; she tried to impart to him some of her confidence, to animate him with her hope, but without success, so she went on without him. A mill was for sale at Jouy, on the banks of the Oise; she paid ready money for it, and a few weeks later the bakery in the Rue Vivienne was independent of every one. She ground her own flour, and from that time business increased considerably. Feeling capable of carrying out large undertakings, and, moreover, desirous of giving up the meannesses of retail trade, Madame Desvarennes, one fine day, sent in a tender for supplying bread to the military hospitals. It was accepted, and from that time the house ranked among the most important. On seeing the Desvarennes take their daring flight, the leading men in the trade had said:

"They have system and activity, and if they do not upset on the way, they will attain a high position."

But the mistress seemed to have the gift of divination. She worked surely--if she struck out one way you might be certain that success was there. In all her enterprises, "good luck" stood close by her; she scented failures from afar, and the firm never made a bad debt. Still Michel continued to tremble. The first mill had been followed by many more; then the old system appeared insufficient to Madame Desvarennes. As she wished to keep up with the increase of business she had steam-mills built,--which are now grinding three hundred million francs' worth of corn every year.

Fortune had favored the house immensely, but Michel continued to tremble. From time to time when the mistress launched out a new business, he timidly ventured on his usual saying:

"Wife, you're going to ruin us."

But one felt it was only for form's sake, and that he himself no longer meant what he said. Madame Desvarennes received this plaintive remonstrance with a calm smile, and answered, maternally, as to a child:

"There, there, don't be frightened."

Then she would set to work again, and direct with irresistible vigor the army of clerks who peopled her counting-houses.

In fifteen years' time, by prodigious efforts of will and energy, Madame Desvarennes had made her way from the lonely and muddy Rue Neuve-Coquenard to the mansion in the Rue Saint-Dominique. Of the bakery there was no longer question. It was some time since the business in the Rue Vivienne had been transferred to the foreman of the shop. The flour trade alone occupied Madame Desvarennes's attention. She ruled the prices in the market; and great bankers came to her office and did business with her on a footing of equality. She did not become any prouder for it, she knew too well the strength and weakness of life to have pride; her former plain dealing had not stiffened into self-sufficiency. Such as one had known her when beginning business, such one found her in the zenith of her fortune. Instead of a woollen gown she wore a silk one, but the color was still black; her language had not become refined; she retained the same blunt familiar accent, and at the end of five minutes' conversation with any one of importance she could not resist calling him "my dear," to come morally near him. Her commands had more fulness. In giving her orders, she had the manner of a commander-in-chief, and it was useless to haggle when she had spoken. The best thing to do was to obey, as well and as promptly as possible.

Placed in a political sphere, this marvellously gifted woman would have been a Madame Roland; born to the throne, she would have been a Catherine II.; there was genius in her. Sprung from the lower ranks, her superiority had given her wealth; had she come from the higher, the great mind might have governed the world.

Still she was not happy; she had been married fifteen years, and her fireside was devoid of a cradle. During the first years she had rejoiced at not having a child. Where could she have found time to occupy herself with a baby? Business engrossed her attention; she had no leisure to amuse herself with trifles. Maternity seemed to her a luxury for rich women; she had her fortune to make. In the struggle against the difficulties attending the enterprise she had begun, she had not had time to look around her and perceive that her home was lonely. She worked from morning till night. Her whole life was absorbed in this work, and when night came, overcome with fatigue, she fell asleep, her head filled with cares which stifled all tricks of the imagination.

Michel grieved, but in silence; his feeble and dependent nature missed a child. He, whose mind lacked occupation, thought of the future. He said to himself that the day when the dreamt-of fortune came would be more welcome if there were an heir to whom to leave it. What was the good of being rich, if the money went to collateral relatives? There was his nephew Savinien, a disagreeable urchin whom he looked on with indifference; and he was biased regarding his brother, who had all but failed several times in business, and to whose aid he had come to save the honor of the name. The mistress had not hesitated to help him, and had prevented the signature of "Desvarennes" being protested. She had not taunted him, having as large a heart as she had a mind. But Michel had felt humiliated to see his own folk make a gap in the financial edifice erected so laboriously by his wife. Out of this had gradually sprung a sense of dissatisfaction with the Desvarennes of the other branch, which manifested itself by a marked coolness, when, by chance, his brother came to the house, accompanied by his son Savinien.

And then the paternity of his brother made him secretly jealous. Why should that incapable fellow, who succeeded in nothing, have a son? It was only those ne'er-do-well sort of people who were thus favored. He, Michel, already called the rich Desvarennes, he had not a son. Was it just? But where is there justice in this world?

The first time that she saw him with a downcast face the mistress had questioned him, and he had frankly expressed his regrets. But he had been so repelled by his wife, in whose heart a great trouble, steadily repressed, however, had been produced, that he never dared to recur to the subject.

He suffered in silence. But he no longer suffered alone. Like an overflowing river that finds an outlet in the valley, which it inundates, the longings for maternity, hitherto repressed by the preoccupations of business, had suddenly seized Madame Desvarennes.

Strong and unyielding, she struggled and would not own herself conquered. Still she became sad. Her voice sounded less sonorously in the offices where she gave an order; her energetic nature seemed subdued. Now she looked around her. She beheld prosperity made stable by incessant work, respect gained by spotless honesty; she had attained the goal which she had marked out in her ambitious dreams, as being paradise itself. Paradise was there; but it lacked the angel. They had no child.

From that day a change came over this woman, slowly but surely; scarcely perceptible to strangers, but easy to be seen by those around her. She became benevolent, and gave away considerable sums of money, especially to children's "Homes." But when the good people who governed these establishments, lured on by her generosity, came to ask her to be on their committee of management, she became angry, asking them if they were joking with her? What interest could those brats have for her? She had other fish to fry. She gave them what they needed, and what more could they want? The fact was she felt weak and troubled before children. But within her a powerful and unknown voice had arisen, and the hour was not far distant when the bitter wave of her regrets was to overflow and be made manifest.

She did not like Savinien, her nephew, and kept all her sweetness for the son of one of their old neighbors in the Rue Neuve-Coquenard, a small haberdasher, who had not been able to get on, but continued humbly to sell thread and needles to the thrifty folks of the neighborhood. The haberdasher, Mother Delarue, as she was called, had remained a widow after one year of married life. Pierre, her boy, had grown up under the shadow of the bakery, the cradle of the Desvarennes's fortunes.

On Sundays the mistress would give him a gingerbread or a cracknel, and amuse herself with his baby prattle. She did not lose sight of him when she removed to the Rue Vivienne. Pierre had entered the elementary school of the neighborhood, and by his precocious intelligence and exceptional application, had not been long in getting to the top of his class. The boy had left school after gaining an exhibition admitting him to the Chaptal College. This hard worker, who was in a fair way of making his own position without costing his relatives anything, greatly interested Madame Desvarennes. She found in this plucky nature a striking analogy to herself. She formed projects for Pierre's future; in fancy she saw him enter the Polytechnic school, and leave it with honors. The young man had the choice of becoming a mining or civil engineer, and of entering the government service.

He was hesitating what to do when the mistress came and offered him a situation in her firm as junior partner; it was a golden bridge that she placed before him. With his exceptional capacities he was not long in giving to the house a new impulse. He perfected the machinery, and triumphantly defied all competition. All this was a happy dream in which Pierre was to her a real son; her home became his, and she monopolized him completely. But suddenly a shadow came o'er the spirit of her dreams. Pierre's mother, the little haberdasher, proud of her son, would she consent to give him up to a stranger? Oh! if Pierre had only been an orphan! But one could not rob a mother of her son! And Madame Desvarennes stopped the flight of her imagination. She followed Pierre with anxious looks; but she forbade herself to dispose of the youth: he did not belong to her.

This woman, at the age of thirty-five, still young in heart, was disturbed by feelings which she strove, but vainly, to rule. She hid them especially from her husband, whose repining chattering she feared. If she had once shown him her weakness he would have overwhelmed her daily with the burden of his regrets. But an unforeseen circumstance placed her at Michel's mercy.

Winter had come, bringing December and its snow. The weather this year was exceptionally inclement, and traffic in the streets was so difficult, business was almost suspended. The mistress left her deserted offices and retired early to her private apartments. The husband and wife spent their evenings alone. They sat there, facing each other, at the fireside. A shade concentrated the light of the lamp upon the table covered with expensive knick-knacks. The ceiling was sometimes vaguely lighted up by a glimmer from the stove which glittered on the gilt cornices. Ensconced in deep comfortable armchairs, the pair respectively caressed their favorite dream without speaking of it.

Madame Desvarennes saw beside her a little pink-and-white baby girl, toddling on the carpet. She heard her words, understood her language, untranslatable to all others than a mother. Then bedtime came. The child, with heavy eyelids, let her little fair-haired head fall on her shoulders. Madame Desvarennes took her in her arms and undressed her quietly, kissing her bare and dimpled arms. It was exquisite enjoyment which stirred her heart deliciously. She saw the cradle, and devoured the child with her eyes. She knew that the picture was a myth. But what did it matter to her? She was happy. Michel's voice broke on her reverie.

"Wife," said he, "this is Christmas Eve; and as there are only us two, suppose you put your slipper on the hearth."

Madame Desvarennes rose. Her eyes vaguely turned toward the hearth on which the fire was dying, and beside the upright of the large sculptured mantelpiece she beheld for a moment a tiny shoe, belonging to the child which she loved to see in her dreams. Then the vision vanished, and there was nothing left but the lonely hearth. A sharp pain tore her swollen heart; a sob rose to her lips, and, slowly, two tears rolled down her cheeks. Michel, quite pale, looked at her in silence; he held out his hand to her, and said, in a trembling voice:

"You were thinking about it, eh?"

Madame Desvarennes bowed her head, twice, silently, and without adding another word, the pair fell into each other's arms and wept.

From that day they hid nothing from each other, and shared their troubles and regrets in common. The mistress unburdened her heart by making a full confession, and Michel, for the first time in his life, learned the depth of soul of his companion to its inmost recesses. This woman, so energetic, so obstinate, was, as it were, broken down. The springs of her will seemed worn out. She felt despondencies and wearinesses until then unknown. Work tired her. She did not venture down to the offices; she talked of giving up business, which was a bad sign. She longed for country air. Were they not rich enough? With their simple tastes so much money was unnecessary. In fact, they had no wants. They would go to some pretty estate in the suburbs of Paris, live there and plant cabbages. Why work? they had no children.

Michel agreed to these schemes. For a long time he had wished for repose. Often he had feared that his wife's ambition would lead them too far. But now, since she stopped of her own accord, it was all for the best.

At this juncture their solicitor informed them that, near to their works, the Cernay estate was to be put up for sale. Very often, when going from Jouy to the mills, Madame Desvarennes had noticed the chateau, the slate roofs of the turrets of which rose gracefully from a mass of deep verdure. The Count de Cernay, the last representative of a noble race, had just died of consumption, brought on by reckless living, leaving nothing behind him but debts and a little girl two years old. Her mother, an Italian singer and his mistress, had left him one morning without troubling herself about the child. Everything was to be sold, by order of the Court.

Some most lamentable incidents had saddened the Count's last hours. The bailiffs had entered the house with the doctor when he came to pay his last call, and the notices of the sale were all but posted up before the funeral was over. Jeanne, the orphan, scared amid the troubles of this wretched end, seeing unknown men walking into the reception-rooms with their hats on, hearing strangers speaking loudly and with arrogance, had taken refuge in the laundry. It was there that Madame Desvarennes found her, playing, plainly dressed in a little alpaca frock, her pretty hair loose and falling on her shoulders. She looked astonished at what she had seen; silent, not daring to run or sing as formerly in the great desolate house whence the master had just been taken away forever.

With the vague instinct of abandoned children who seek to attach themselves to some one or some thing, Jeanne clung to Madame Desvarennes, who, ready to protect, and longing for maternity, took the child in her arms. The gardener's wife acted as guide during her visit over the property. Madame Desvarennes questioned her. She knew nothing of the child except what she had heard from the servants when they gossiped in the evenings about their late master. They said Jeanne was a bastard. Of her relatives they knew nothing. The Count had an aunt in England who was married to a rich lord; but he had not corresponded with her lately. The little one then was reduced to beggary as the estate was to be sold.

The gardener's wife was a good woman and was willing to keep the child until the new proprietor came; but when once affairs were settled, she would certainly go and make a declaration to the mayor, and take her to the workhouse. Madame Desvarennes listened in silence. One word only had struck her while the woman was speaking. The child was without support, without ties, and abandoned like a poor lost dog. The little one was pretty too; and when she fixed her large deep eyes on that improvised mother, who pressed her so tenderly to her heart, she seemed to implore her not to put her down, and to carry her away from the mourning that troubled her mind and the isolation that froze her heart.

Madame Desvarennes, very superstitious, like a woman of the people, began to think that, perhaps, Providence had brought her to Cernay that day and had placed the child in her path. It was perhaps a reparation which heaven granted her, in giving her the little girl she so longed for. Acting unhesitatingly, as she did in everything, she left her name with the woman, carried Jeanne to her carriage, and took her to Paris, promising herself to make inquiries to find her relatives.

A month later, the property of Cernay pleasing her, and the researches for Jeanne's friends not proving successful, Madame Desvarennes took possession of the estate and the child into the bargain.

Michel welcomed the child without enthusiasm. The little stranger was indifferent to him; he would have preferred adopting a boy. The mistress was delighted. Her maternal instincts, so long stifled, developed fully. She made plans for the future. Her energy returned; she spoke loudly and firmly. But in her appearance there was revealed an inward contentment never remarked before, which made her sweeter and more benevolent. She no longer spoke of retiring from business. The discouragement which had seized her left her as if by magic. The house which had been so dull for some months became noisy and gay. The child, like a sunbeam, had scattered the clouds.

It was then that the most unlooked-for phenomenon, which was so considerably to influence Madame Desvarennes's life, occurred. At the moment when the mistress seemed provided by chance with the heiress so much longed for, she learned with surprise that she was about to become a mother! After sixteen years of married life, this discovery was almost a discomfiture. What would have been delight formerly was now a cause for fear. She, almost an old woman!

There was an incredible commotion in the business world when the news became known. The younger branch of Desvarennes had witnessed Jeanne's arrival with little satisfaction, and were still more gloomy when they learned that the chances of their succeeding to great wealth were over. Still they did not lose all hopes. At thirty-five years of age one cannot always tell how these little affairs will come off. An accident was possible. But none occurred; all passed off well.

Madame Desvarennes was as strong physically as she was morally, and proved victorious by bringing into the world a little girl, who was named Michelins in honor of her father. The mistress's heart was large enough to hold two children; she kept the orphan she had adopted, and brought her up as if she had been her very own. Still there was soon an enormous difference in her manner of loving Jeanne and Michelins. This mother had for the long-wished-for child an ardent, mad, passionate love like that of a tigress for her cubs. She had never loved her husband. All the tenderness which had accumulated in her heart blossomed, and it was like spring.

This autocrat, who had never allowed contradiction, and before whom all her dependents bowed either with or against the grain, was now led in her turn; the bronze of her character became like wax in the little pink hands of her daughter. The commanding woman bent before the little fair head. There was nothing good enough for Micheline. Had the mother owned the world she would have placed it at the little one's feet. One tear from the child upset her. If on one of the most important subjects Madame Desvarennes had said "No," and Micheline came and said "Yes," the hitherto resolute will became subordinate to the caprice of a child. They knew it in the house and acted upon it. This manoeuvre succeeded each time, although Madame Desvarennes had seen through it from the first. It appeared as if the mother felt a secret joy in proving under all circumstances the unbounded adoration which she felt for her daughter. She often said:

"Pretty as she is, and rich as I shall make her, what husband will be worthy of Micheline? But if she believes me when it is time to choose one, she will prefer a man remarkable for his intelligence, and will give him her fortune as a stepping-stone to raise him as high as she chooses him to go."

Inwardly she was thinking of Pierre Delarue, who had just taken honors at the Polytechnic school, and who seemed to have a brilliant career before him. This woman, humbly born, was proud of her origin, and sought a plebeian for her son-in-law, to put into his hand a golden tool powerful enough to move the world.

Micheline was ten years old when her father died. Alas, Michel was not a great loss. They wore mourning for him; but they hardly noticed that he was absent. His whole life had been a void. Madame Desvarennes, it is sad to say, felt herself more mistress of her child when she was a widow. She was jealous of Micheline's affections, and each kiss the child gave her father seemed to the mother to be robbed from her. With this fierce tenderness, she preferred solitude around this beloved being.

At this time Madame Desvarennes was really in the zenith of womanly splendor. She seemed taller, her figure had straightened, vigorous and powerful. Her gray hair gave her face a majestic appearance. Always surrounded by a court of clients and friends, she seemed like a sovereign. The fortune of the firm was not to be computed. It was said Madame Desvarennes did not know how rich she was.

Jeanne and Micheline grew up amid this colossal prosperity. The one, tall, brown-haired, with blue eyes changing like the sea; the other, fragile, fair, with dark dreamy eyes. Jeanne, proud, capricious, and inconstant; Micheline, simple, sweet, and tenacious. The brunette inherited from her reckless father and her fanciful mother a violent and passionate nature; the blonde was tractable and good like Michel, but resolute and firm like Madame Desvarennes. These two opposite natures were congenial, Micheline sincerely loving Jeanne, and Jeanne feeling the necessity of living amicably with Micheline, her mother's idol, but inwardly enduring with difficulty the inequalities which began to exhibit themselves in the manner with which the intimates of the house treated the one and the other. She found these flatteries wounding, and thought Madame Desvarennes's preferences for Micheline unjust.

All these accumulated grievances made Jeanne conceive the wish one morning of leaving the house where she had been brought up, and where she now felt humiliated. Pretending to long to go to England to see that rich relative of her father, who, knowing her to be in a brilliant society, had taken notice of her, she asked Madame Desvarennes to allow her to spend a few weeks from home. She wished to try the ground in England, and see what she might expect in the future from her family. Madame Desvarennes lent herself to this whim, not guessing the young girl's real motive; and Jeanne, well attended, went to her aunt's home in England.

Madame Desvarennes, besides, had attained the summit of her hopes, and an event had just taken place which preoccupied her. Micheline, deferring to her mother's wishes, had decided to allow herself to be betrothed to Pierre Delarue, who had just lost his mother, and whose business improved daily. The young girl, accustomed to treat Pierre like a brother, had easily consented to accept him as her future husband.

Jeanne, who had been away for six months, had returned sobered and disillusioned about her family. She had found them kind and affable, had received many compliments on her beauty, which was really remarkable, but had not met with any encouragement in her desires for independence. She came home resolved not to leave until she married. She arrived in the Rue Saint-Dominique at the moment when Pierre Delarue, thirsting with ambition, was leaving his betrothed, his relatives, and gay Paris to undertake engineering work on the coasts of Algeria and Tunis that would raise him above his rivals. In leaving, the young man did not for a moment think that Jeanne was returning from England at the same hour with trouble for him in the person of a very handsome cavalier, Prince Serge Panine, who had been introduced to her at a ball during the London season. Mademoiselle de Cernay, availing herself of English liberty, was returning escorted only by a maid in company with the Prince. The journey had been delightful. The tete-a-tete travelling had pleased the young people, and on leaving the train they had promised to see each other again. Official balls facilitated their meeting; Serge was introduced to Madame Desvarennes as being an English friend, and soon became the most assiduous partner of Jeanne and Micheline. It was thus, under the most trivial pretext, that the man gained admittance to the house where he was to play such an important part.

CHAPTER II

THE GALLEY-SLAVE OF PLEASURE

One morning in the month of May, 1879, a young man, elegantly attired, alighted from a well-appointed carriage before the door of Madame Desvarennes's house. The young man passed quickly before the porter in uniform, decorated with a military medal, stationed near the door. The visitor found himself in an anteroom which communicated with several corridors. A messenger was seated in the depth of a large armchair, reading the newspaper, and not even lending an inattentive ear to the whispered conversation of a dozen canvassers, who were patiently awaiting their turn for gaining a hearing. On seeing the young man enter by the private door, the messenger rose, dropped his newspaper on the armchair, hastily raised his velvet skullcap, tried to smile, and made two steps forward.

"Good-morning, old Felix," said the young man, in a friendly tone to the messenger. "Is my aunt within?"

"Yes, Monsieur Savinien, Madame Desvarennes is in her office; but she has been engaged for more than an hour with the Financial Secretary of the War Department."

In uttering these words old Felix put on a mysterious and important air, which denoted how serious the discussions going on in the adjoining room seemed to his mind.

"You see," continued he, showing Madame Desvarennes's nephew the anteroom full of people, "madame has kept all these waiting since this morning, and perhaps she won't see them."

"I must see her though," murmured the young man.

He reflected a moment, then added:

"Is Monsieur Marechal in?"

"Yes, sir, certainly. If you will allow me I will announce you."

"It is unnecessary."

And, stepping forward, he entered the office adjoining that of Madame Desvarennes.

Seated at a large table of black wood, covered with bundles of papers and notes, a young man was working. He was thirty years of age, but appeared much older. His prematurely bald forehead, and wrinkled brow, betokened a life of severe struggles and privations, or a life of excesses and pleasures. Still those clear and pure eyes were not those of a libertine, and the straight nose solidly joined to the face was that of a searcher. Whatever the cause, the man was old before his time.

On hearing the door of his office open, he raised his eyes, put down his pen, and was making a movement toward his visitor, when the latter interrupted him quickly with these words:

"Don't stir, Marechal, or I shall be off! I only came in until Aunt Desvarennes is at liberty; but if I disturb you I will go and take a turn, smoke a cigar, and come back in three quarters of an hour."

"You do not disturb me, Monsieur Savinien; at least not often enough, for be it said, without reproaching you, it is more than three months since we have seen anything of you. There, the post is finished. I was writing the last addresses."

And taking a heavy bundle of papers off the desk, Marechal showed them to Savinien.

"Gracious! It seems that business is going on well here."

"Better and better."

"You are making mountains of flour."

"Yes; high as Mont Blanc; and then, we now have a fleet."

"What! a fleet?" cried Savinien, whose face expressed doubt and surprise at the same time.

"Yes, a steam fleet. Last year Madame Desvarennes was not satisfied with the state in which her corn came from the East. The corn was damaged owing to defective stowage; the firm claimed compensation from the steamship company. The claim was only moderately satisfied, Madame Desvarennes got vexed, and now we import our own. We have branches at Smyrna and Odessa."

"It is fabulous! If it goes on, my aunt will have an administration as important as that of a European state. Oh! you are happy here, you people; you are busy. I amuse myself! And if you knew how it wearies me! I am withering, consuming myself, I am longing for business."

And saying these words, young Monsieur Desvarennes allowed a sorrowful moan to escape him.

"It seems to me," said Marechal, "that it only depends upon yourself to do as much and more business than any one?"

"You know well enough that it is not so," sighed Savinien; "my aunt is opposed to it."

"What a mistake!" cried Marechal, quickly. "I have heard Madame Desvarennes say more than twenty times how she regretted your being unemployed. Come into the firm, you will have a good berth in the counting-house."

"In the counting-house!" cried Savinien, bitterly; "there's the sore point. Now look here; my friend, do you think that an organization like mine is made to bend to the trivialities of a copying clerk's work? To follow the humdrum of every-day routine? To blacken paper? To become a servant?--me! with what I have in my brain?"

And, rising abruptly, Savinien began to walk hurriedly up and down the room, disdainfully shaking his little head with its low forehead on which were plastered a few fair curls (made with curling-irons), with the indignant air of an Atlas carrying the world on his shoulders.

"Oh, I know very well what is at the bottom of the business--my aunt is jealous of me because I am a man of ideas. She wishes to be the only one of the family who possesses any. She thinks of binding me down to a besotting work," continued he, "but I won't have it. I know what I want! It is independence of thought, bent on the solution of great problems--that is, a wide field to apply my discoveries. But a fixed rule, common law, I could not submit to it."

"It is like the examinations," observed Marechal, looking slyly at young Desvarennes, who was drawing himself up to his full height; "examinations never suited you."

"Never," said Savinien, energetically. "They wished to get me into the Polytechnic School; impossible! Then the Central School; no better. I astonished the examiners by the novelty of my ideas. They refused me."

"Well, you know," retorted Marechal, "if you began by overthrowing their theories--"

"That's it!" cried Savinien, triumphantly. "My mind is stronger than I; I must let my imagination have free run, and no one will ever know what that particular turn of mind has cost me. Even my family do not think me serious. Aunt Desvarennes has forbidden any kind of enterprise, under pretence that I bear her name, and that I might compromise it because I have twice failed. My aunt paid, it is true. Do you think it is generous of her to take advantage of my situation, and prohibit my trying to succeed? Are inventors judged by three or four failures? If my aunt had allowed me I should have astonished the world."

"She feared, above all," said Marechal, simply, "to see you astonishing the Tribunal of Commerce."

"Oh! you, too," moaned Savinien, "are in league with my enemies; you make no account of me."

And young Desvarennes sank as if crushed into an armchair and began to lament. He was very unhappy at being misunderstood. His aunt allowed him three thousand francs a month on condition that he would not make use of his ten fingers. Was it moral? Then he with such exuberant vigor had to waste it on pleasure and seeing life to the utmost. He passed his time in theatres, at clubs, restaurants, in boudoirs. He lost his time, his money, his hair, his illusions. He bemoaned his lot, but continued, only to have something to do. With grim sarcasm he called himself the galley-slave of pleasure. And notwithstanding all these consuming excesses, he asserted that he could not render his imagination barren. Amid the greatest follies at suppers, during the clinking of glasses; in the excitement of the dance-inspirations came to him in flashes, he made prodigious discoveries.

And as Marechal ventured a timid "Oh!" tinged with incredulity, Savinien flew into a passion. Yes; he had invented something astonishing; he saw fortune within reach, and he thought the bargain made with his aunt very unjust. Therefore he had come to break it, and to regain his liberty.

Marechal looked at the young man while he was explaining with animation his ambitious projects. He scrutinized that flat forehead within which the dandy asserted so many good ideas were hidden. He measured that slim form bent by wild living, and asked himself how that degenerate being could struggle against the difficulties of business. A smile played on his lips. He knew Savinien too well not to be aware that he was a prey to one of those attacks of melancholy which seized on him when his funds were low.

On these occasions, which occurred frequently, the young man had longings for business, which Madame Desvarennes stopped by asking: "How much?" Savinien allowed himself to be with difficulty induced to consent to renounce the certain profits promised, as he said, by his projected enterprise. At last he would capitulate, and with his pocket well lined, nimble and joyful, he returned to his boudoirs, race-courses, fashionable restaurants, and became more than ever the galley-slave of pleasure.

"And Pierre?" asked young Desvarennes, suddenly and quickly changing the subject. "Have you any news of him?"

Marechal became serious. A cloud seemed to have come across his brow; he gravely answered Savinien's question.

Pierre was still in the East. He was travelling toward Tunis, the coast of which he was exploring. It was a question of the formation of an island sea by taking the water through the desert. It would be a colossal undertaking, the results of which would be considerable as regarded Algeria. The climate would be completely changed, and the value of the colony would be increased tenfold, because it would become the most fertile country in the world. Pierre had been occupied in this undertaking for more than a year with unequalled ardor; he was far from his home, his betrothed, seeing only the goal to be attained; turning a deaf ear to all that would distract his attention from the great work, to the success of which he hoped to contribute gloriously.

"And don't people say," resumed Savinien with an evil smile, "that during his absence a dashing young fellow is busy luring his betrothed away from him?"

At these words Marechal made a quick movement.

"It is false," he interrupted; "and I do not understand how you, Monsieur Desvarennes, should be the bearer of such a tale. To admit that Mademoiselle Micheline could break her word or her engagements is to slander her, and if any one other than you--"

"There, there, my dear friend," said Savinien, laughing, "don't get into a rage. What I say to you I would not repeat to the first comer; besides, I am only the echo of a rumor that has been going the round during the last three weeks. They even give the name of him who has been chosen for the honor and pleasure of such a brilliant conquest. I mean Prince Serge Panine."

"As you have mentioned Prince Panine," replied Marechal, "allow me to tell you that he has not put his foot inside Madame Desvarennes's door for three weeks. This is not the way of a man about to marry the daughter of the house."

"My dear fellow, I only repeat what I have heard. As for me, I don't know any more. I have kept out of the way for more than three months. And besides, it matters little to me whether Micheline be a commoner or a princess, the wife of Delarue or of Panine. I shall be none the richer or the poorer, shall I? Therefore I need not care. The dear child will certainly have millions enough to marry easily. And her adopted sister, the stately Mademoiselle Jeanne, what has become of her?"

"Ah! as to Mademoiselle de Cernay, that is another affair," cried Marechal.

And as if wishing to divert the conversation in an opposite direction to which Savinien had led it a moment before, he spoke readily of Madame Desvarennes's adopted daughter. She had made a lively impression on one of the intimate friends of the house--the banker Cayrol, who had offered his name and his fortune to the fair Jeanne.

This was a cause of deep amazement to Savinien. What! Cayrol! The shrewd close--fisted Auvergnat! A girl without a fortune! Cayrol Silex as he was called in the commercial world on account of his hardness. This living money-bag had a heart then! It was necessary to believe it since both money-bag and heart had been placed at Mademoiselle de Cernay's feet. This strange girl was certainly destined to millions. She had just missed being Madame Desvarennes's heiress, and now Cayrol had taken it into his head to marry her.

But that was not all. And when Marechal told Savinien that the fair Jeanne flatly refused to become the wife of Cayrol, there was an outburst of joyful exclamations. She refused! By Jove, she was mad! An unlooked-for marriage--for she had not a penny, and had most extravagant notions. She had been brought up as if she were to live always in velvet and silks--to loll in carriages and think only of her pleasure. What reason did she give for refusing him! None. Haughtily and disdainfully she had declared that she did not love "that man," and that she would not marry him.

When Savinien heard these details his rapture increased. One thing especially charmed him: Jeanne's saying "that man," when speaking of Cayrol. A little girl who was called "De Cernay" just as he might call himself "Des Batignolles" if he pleased: the natural and unacknowledged daughter of a Count and of a shady public singer! And she refused Cayrol, calling him "that man." It was really funny. And what did worthy Cayrol say about it?

When Marechal declared that the banker had not been damped by this discouraging reception, Savinien said it was human nature. The fair Jeanne scorned Cayrol and Cayrol adored her. He had often seen those things happen. He knew the baggages so well! Nobody knew more of women than he did. He had known some more difficult to manage than proud Mademoiselle Jeanne.

An old leaven of hatred had festered in Savinien's heart against Jeanne since the time when the younger branch of the Desvarennes had reason to fear that the superb heritage was going to the adopted daughter. Savinien had lost the fear, but had kept up the animosity. And everything that could happen to Jeanne of a vexing or painful nature would be witnessed by him with pleasure.

He was about to encourage Marechal to continue his revelations, and had risen and was leaning on the desk. With his face excited and eager, he was preparing his question, when, through the door which led to Madame Desvarennes's office, a confused murmur of voices was heard. At the same time the door was half opened, held by a woman's hand, square, with short fingers, a firm-willed and energetic hand. At the same time, the last words exchanged between Madame Desvarennes and the Financial Secretary of the War Office were distinctly audible. Madame Desvarennes was speaking, and her voice sounded clear and plain; a little raised and vibrating. There seemed a shade of anger in its tone.

"My dear sir, you will tell the Minister that does not suit me. It is not the custom of the house. For thirty-five years I have conducted business thus, and I have always found it answer. I wish you good-morning."

The door of the office facing that which Madame Desvarennes held closed, and a light step glided along the corridor. It was the Financial Secretary's. The mistress appeared.

Marechal rose hastily. As to Savinien, all his resolution seemed to have vanished at the sound of his aunt's voice, for he had rapidly gained a corner of the room, and seated himself on a leather-covered sofa, hidden behind an armchair, where he remained perfectly quiet.

"Do you understand that, Marechal?" said dame Desvarennes; "they want to place a resident agent at the mill on pretext of checking things. They say that all military contractors are obliged to submit to it. My word, do they take us for thieves, the rascals? It is the first time that people have seemed to doubt me. And it has enraged me. I have been arguing for a whole hour with the man they sent me. I said to him, 'My dear sir, you may either take it or leave it. Let us start from this point: I can do without you and you cannot do without me. If you don't buy my flour, somebody else will. I am not at all troubled about it. But as to having any one here who would be as much master as myself, or perhaps more, never! I am too old to change my customs.' Thereupon the Financial Secretary left. There! And, besides, they change their Ministry every fortnight. One would never know with whom one had to deal. Thank you, no."

While talking thus with Marechal, Madame Desvarennes was walking about the office. She was still the same woman with the broad prominent forehead. Her hair, which she wore in smooth plaits, had become gray, but the sparkle of her dark eyes only seemed the brighter from this. She had preserved her splendid teeth, and her smile had remained young and charming. She spoke with animation, as usual, and with the gestures of a man. She placed herself before her secretary, seeming to appeal to him as a witness of her being in the right. During the hour with the official personage she had been obliged to contain herself. She unburdened herself to Marechal, saying just what she thought.

But all at once she perceived Savinien, who was waiting to show himself now that she had finished. The mistress turned sharply to the young man, and frowned slightly:

"Hallo! you are there, eh? How is it that you could leave your fair friends?"

"But, aunt, I came to pay you my respects."

"No nonsense now; I've no time," interrupted the mistress. "What do you want?"

Savinien, disconcerted by this rude reception, blinked his eyes, as if seeking some form to give his request; then, making up his mind, he said:

"I came to see you on business."

"You on business?" replied Madame Desvarennes, with a shade of astonishment and irony.

"Yes, aunt, on business," declared Savinien, looking down as if he expected a rebuff.

"Oh, oh, oh!" said Madame Desvarennes, "you know our agreement; I give you an allowance--"

"I renounce my income," interrupted Savinien, quickly, "I wish to take back my independence. The transfer I made has already cost me too dear. It's a fool's bargain. The enterprise which I am going to launch is superb, and must realize immense profits. I shall certainly not abandon it."

While speaking, Savinien had become animated and had regained his self-possession. He believed in his scheme, and was ready to pledge his future. He argued that his aunt could not blame him for giving proof of his energy and daring, and he discoursed in bombastic style.

"That's enough!" cried Madame Desvarennes, interrupting her nephew's oration. "I am very fond of mills, but not word-mills. You are talking too much about it to be sincere. So many words can only serve to disguise the nullity of your projects. You want to embark in speculation? With what money?"

"I contribute the scheme and some capitalists will advance the money to start with; we shall then issue shares!"

"Never in this life! I oppose it. You! With a responsibility. You! Directing an undertaking. You would only commit absurdities. In fact, you want to sell an idea, eh? Well, I will buy it."

"It is not only the money I want," said Savinien, with an indignant air, "it is confidence in my ideas, it is enthusiasm on the part of my shareholders, it is success. You don't believe in my ideas, aunt!"

"What does it matter to you, if I buy them from you? It seems to me a pretty good proof of confidence. Is that settled?"

"Ah, aunt, you are implacable!" groaned Savinien. "When you have laid your hand upon any one, it is all over. Adieu, independence; one must obey you. Nevertheless, it was a vast and beautiful conception."

"Very well. Marechal, see that my nephew has ten thousand francs. And you, Savinien, remember that I see no more of you."

"Until the money is spent!" murmured Marechal, in the ear of Madame Desvarennes's nephew.

And taking him by the arm he was leading him toward the safe when the mistress turned to Savinien and said:

"By the way, what is your invention?"

"Aunt, it is a threshing machine," answered the young man, gravely.

"Rather a machine for coining money," said the incorrigible Marechal, in an undertone.

"Well; bring me your plans," resumed Madame Desvarennes, after having reflected a moment. "Perchance you may have hit upon something."

The mistress had been generous, and now the woman of business reasserted herself and she thought of reaping the benefit.

Savinien seemed very confused at this demand, and as his aunt gave him an interrogative look, he confessed:

"There are no drawings made as yet."

"No drawings as yet?" cried the mistress. "Where then is your invention?"

"It is here," replied Savinien, and with an inspired gesture he struck his narrow forehead.

Madame Desvarennes and Marechal could not resist breaking out into a laugh.

"And you were already talking of issuing shares?" said the mistress. "Do you think people would have paid their money with your brain as sole guarantee? You! Get along; I am the only one to make bargains like that, and you are the only one with whom I make them. Go, Marechal, give him his money; I won't gainsay it. But you are a trickster, as usual!"

CHAPTER III

PIERRE RETURNS

By a wave of her hand she dismissed Savinien, who, abashed, went out with Marechal. Left alone, she seated herself at her secretary's desk, and taking the pile of letters she signed them. The pen flew in her fingers, and on the paper was displayed her name, written in large letters in a man's handwriting.

She had been occupied thus for about a quarter of an hour when Marechal reappeared. Behind him came a stout thickset man of heavy build, and gorgeously dressed. His face, surrounded by a bristly dark brown beard, and his eyes overhung by bushy eyebrows, gave him, at the first glance, a harsh appearance. But his mouth promptly banished this impression. His thick and sensual lips betrayed voluptuous tastes. A disciple of Lavater or Gall would have found the bump of amativeness largely developed.

Marechal stepped aside to allow him to pass.

"Good-morning, mistress," said he familiarly, approaching Madame Desvarennes.

The mistress raised her head quickly, and said:

"Ah! it's you, Cayrol! That's capital! I was just going to send for you."

Jean Cayrol, a native of Cantal, had been brought up amid the wild mountains of Auvergne. His father was a small farmer in the neighborhood of Saint-Flour, scraping a miserable pittance from the ground for the maintenance of his family. From the age of eight years Cayrol had been a shepherd-boy. Alone in the quiet and remote country, the child had given way to ambitious dreams. He was very intelligent, and felt that he was born to another sphere than that of farming.

Thus, at the first opportunity which had occurred to take him into a town, he was found ready. He went as servant to a banker at Brioude. There, in the service of this comparatively luxurious house, he got smoothed down a little, and lost some of his clumsy loutishness. Strong as an ox, he did the work of two men, and at night, when in his garret, fell asleep learning to read. He was seized by the ambition to get on. No pains were to be spared to gain his goal.

His master having been elected a member of the Chamber of Deputies, Cayrol accompanied him to Paris. Life in the capital finished the turmoil of Cayrol's brain. Seeing the prodigious activity of the great city on whose pavements fortunes sprang up in a day like mushrooms, the Auvergnat felt his moral strength equal to the occasion, and leaving his master, he became clerk to a merchant in the Rue du Sentier.

There, for four years, he studied commerce, and gained much experience. He soon learned that it was only in financial transactions that large fortunes were to be rapidly made. He left the Rue du Sentier, and found a place at a stock-broker's. His keen scent for speculation served him admirably. After the lapse of a few years he had charge of the business. His position was getting better; he was making fifteen thousand francs per annum, but that was nothing compared to his dreams. He was then twenty-eight years of age. He felt ready to do anything to succeed, except something unhandsome, for this lover of money would have died rather than enrich himself by dishonest means.

It was at this time that his lucky star threw him in Madame Desvarennes's way. The mistress, understanding men, guessed Cayrol's worth quickly. She was seeking a banker who would devote himself to her interests. She watched the young man narrowly for some time; then, sure she was not mistaken as to his capacity, she bluntly proposed to give him money to start a business. Cayrol, who had already saved eighty thousand francs, received twelve hundred thousand from Madame Desvarennes, and settled in the Rue Taitbout, two steps from the house of Rothschild.

Madame Desvarennes had made a lucky hit in choosing Cayrol as her confidential agent. This short, thickset Auvergnat was a master of finance, and in a few years had raised the house to an unexpected degree of prosperity. Madame Desvarennes had drawn considerable sums as interest on the money lent, and the banker's fortune was already estimated at several millions. Was it the happy influence of Madame Desvarennes that changed everything she touched into gold, or were Cayrol's capacities really extraordinary? The results were there and that was sufficient. They did not trouble themselves over and above that.

The banker had naturally become one of the intimates of Madame Desvarennes's house. For a long time he saw Jeanne without particularly noticing her. This young girl had not struck his fancy. It was one night at a ball, on seeing her dancing with Prince Panine, that he perceived that she was marvellously engaging. His eyes were attracted by an invincible power and followed her graceful figure whirling through the waltz. He secretly envied the brilliant cavalier who was holding this adorable creature in his arms, who was bending over her bare shoulders, and whose breath lightly touched her hair. He longed madly for Jeanne, and from that moment thought only of her.

The Prince was then very friendly with Mademoiselle de Cernay; he overwhelmed her with kind attentions. Cayrol watched him to see if he spoke to her of love, but Panine was a past master in these drawing-room skirmishes, and the banker got nothing for his pains. That Cayrol was tenacious has been proved. He became intimate with the Prince. He tendered him such little services as create intimacy, and when he was sure of not being repulsed with haughtiness, he questioned Serge. Did he love Mademoiselle de Cernay? This question, asked in a trembling voice and with a constrained smile, found the Prince quite calm. He answered lightly that Mademoiselle de Cernay was a very agreeable partner, but that he had never dreamed of offering her his homage. He had other projects in his head. Cayrol pressed the Prince's hand violently, made a thousand protestations of devotedness, and finally obtained his complete confidence.

Serge loved Mademoiselle Desvarennes, and it was to become intimate with her that he had so eagerly sought her friend's company. Cayrol, in learning the Prince's secret, resumed his usual reserved manner. He knew that Micheline was engaged to Pierre Delarue, but still, women were so whimsical! Who could tell? Perhaps Mademoiselle Desvarennes had looked favorably upon the handsome Serge.

He was really admirable to view, this Panine, with his blue eyes, pure as a maiden's, and his long fair mustache falling on each side of his rosy mouth. He had a truly royal bearing, and was descended from an ancient aristocratic race; he had a charming hand and an arched foot, enough to make a woman envious. Soft and insinuating with his tender voice and sweet Sclavonic accent, he was no ordinary man, but one usually creating a great impression wherever he went.

His story was well known in Paris. He was born in the province of Posen, so violently seized on by Prussia, that octopus of Europe. Serge's father had been killed during the insurrection of 1848, and he, when a year old, was brought by his uncle, Thaddeus Panine, to France, and was educated at the College Rollin, where he had not acquired over much learning.

In 1866, at the moment when war broke out between Prussia and Austria, Serge was eighteen years old. By his uncle's orders he had left Paris, and had entered himself for the campaign in an Austrian cavalry regiment. All who bore the name of Panine, and had strength to hold a sword or carry a gun, had risen to fight the oppressor of Poland. Serge, during this short and bloody struggle, showed prodigies of valor. On the night of Sadowa, out of seven bearing the name of Panine, who had served against Prussia, five were dead, one was wounded; Serge alone was untouched, though red with the blood of his uncle Thaddeus, who was killed by the bursting of a shell. All these Panines, living or dead, had gained honors. When they were spoken of before Austrians or Poles, they were called heroes.

Such a man was a dangerous companion for a young, simple, and artless girl like Micheline. His adventures were bound to please her imagination, and his beauty sure to charm her eyes. Cayrol was a prudent man; he watched, and it was not long before he perceived that Micheline treated the Prince with marked favor. The quiet young girl became animated when Serge was there. Was there love in this transformation? Cayrol did not hesitate. He guessed at once that the future would be Panine's, and that the maintenance of his own influence in the house of Desvarennes depended on the attitude which he was about to take. He passed over to the side of the newcomer with arms and baggage, and placed himself entirely at his disposal.

It was he who three weeks before, in the name of Panine, had made overtures to Madame Desvarennes. The errand had been difficult, and the banker had turned his tongue several times in his mouth before speaking. Still, Cayrol could overcome all difficulties. He was able to explain the object of his mission without Madame flying into a passion. But, the explanation over, there was a terrible scene. He witnessed one of the most awful bursts of rage that it was possible to expect from a violent woman. The mistress treated the friend of the family as one would not have dared to treat a petty commercial traveller who came to a private house to offer his wares. She showed him the door, and desired him not to darken the threshold again.

But if Cayrol was resolute he was equally patient. He listened without saying a word to the reproaches of Madame Desvarennes, who was exasperated that a candidate should be set up in opposition to the son-in-law of her choosing. He did not go, and when Madame Desvarennes was a little calmed by the letting out of her indignation, he argued with her. The mistress was too hasty about the business; it was no use deciding without reflecting. Certainly, nobody esteemed Pierre Delarue more than he did; but it was necessary to know whether Micheline loved him. A childish affection was not love, and Prince Panine thought he might hope that Mademoiselle Desvarennes----

The mistress did not allow Cayrol to finish his sentence; she rang the bell and asked for her daughter. This time, Cayrol prudently took the opportunity of disappearing. He had opened fire; it was for Micheline to decide the result of the battle. The banker awaited the issue of the interview between mother and daughter in the next room. Through the door he heard the irritated tones of Madame Desvarennes, to which Micheline answered softly and slowly. The mother threatened and stormed. Coldly and quietly the daughter received the attack. The tussle lasted about an hour, when the door reopened and Madame Desvarennes appeared, pale and still trembling, but calmed. Micheline, wiping her beautiful eyes, still wet with tears, regained her apartment.

"Well," said Cayrol timidly, seeing the mistress standing silent and absorbed before him; "I see with pleasure that you are less agitated. Did Mademoiselle Micheline give you good reasons?"

"Good reasons!" cried Madame Desvarennes with a violent gesture, last flash of the late storm. "She cried, that's all. And you know when she cries I no longer know what I do or say! She breaks my heart with her tears. And she knows it. Ah! it is a great misfortune to love children too much!"

This energetic woman was conquered, and yet understood that she was wrong to allow herself to be conquered. She fell into a deep reverie, and forgot that Cayrol was present. She thought of the future which she had planned for Micheline, and which the latter carelessly destroyed in an instant.