Read and listen to the book A Country Sweetheart by Russell, Dora.

Audiobook: A Country Sweetheart by Russell, Dora

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Country Sweetheart, by Dora Russell

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

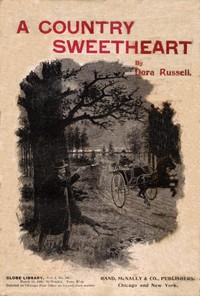

Title: A Country Sweetheart

Author: Dora Russell

Release Date: November 4, 2014 [EBook #47282]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A COUNTRY SWEETHEART ***

Produced by Greg Weeks and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

A COUNTRY SWEETHEART

BY DORA RUSSELL, AUTHOR OF "HIS WILL AND HERS," "THE BROKEN SEAL," "THE LAST SIGNAL," ETC.

CHICAGO AND NEW YORK: RAND, McNALLY & COMPANY, PUBLISHERS.

THE SONG OF THE "No. 9."

My dress is of fine polished oak, As rich as the finest fur cloak, And for handsome design You just should see mine-- No. 9, No. 9.

I'm beloved by the poor and the rich, For both I impartially stitch; In the cabin I shine, In the mansion I'm fine-- No. 9, No. 9.

I never get surly nor tired, With zeal I always am fired; To hard work I incline, For rest I ne'er pine-- No. 9, No. 9.

I am easily purchased by all, With installments that monthly do fall, And when I am thine, Then life is benign-- No. 9, No. 9.

To the Paris Exposition I went, Upon getting the Grand Prize intent; I left all behind, The Grand Prize was mine-- No. 9, No. 9.

At the Universal Exposition of 1889, at Paris, France, the best sewing machines of the world, including those of America, were in competition. They were passed upon by a jury composed of the best foreign mechanical experts, two of whom were the leading sewing machine manufacturers of France. This jury, after exhaustive examination and tests, adjudged that the Wheeler & Wilson machines were the best of all, and awarded the company the highest prize offered--the GRAND PRIZE--giving other companies only gold, silver, and bronze medals.

The French government, as a further recognition of superiority, decorated Mr. Nathaniel Wheeler, president of the company, with the Cross of the Legion of Honor--the most prized honor of France.

The No. 9, for family use, and the No. 12, for manufacturing uses, are the best in the world to-day.

And now, when you want a sewing machine, if you do not get the best it will be your own fault.

Ask your sewing machine dealer for the No. 9 Wheeler & Wilson machine. If he doesn't keep them, write to us for descriptive catalogue and terms. Agents wanted in all unoccupied territory.

WHEELER & WILSON MFG. CO., CHICAGO, ILL.

[Illustration] SCOTCH ROLLED OATS

ARE GOOD OATS

Packed in Two-pound packages only.

ALL GROCERS HANDLE THEM.

[Illustration] THE Napoleon AND THE Josephine

Have an established reputation as

WHEELS OF HIGH CLASS.

This reputation has resulted from a combination of the

Best Materials, Superb Finish, and Conscientious Workmanship.

The Jenkins Cycle Co., 18-20 Custom House Place, Write for Catalog. CHICAGO.

[Illustration: Ride a MONARCH and keep in front MONARCH CYCLE MFG CO CHICAGO NEW YORK LONDON]

CHEW [Illustration] "Kis-Me" [Illustration: IMPORTED KEY RING] Gum

Send us 3 cents and 3 "Kis-Me" Gum wrappers, or 10 cents in stamps or coin, and we will mail you an elegant imported steel key ring as shown by above cut. Throw your old ring away and get a fine one.

KIS-ME GUM CO., Louisville, Ky.

READ Sons and Fathers BY HARRY STILLWELL EDWARDS.

The Story that won the $10,000 Prize in The Chicago Record's Competition.

Bound in English Linen with Gold Back and Side Stamps. Price $1.25.

RAND, McNALLY & CO., PUBLISHERS, CHICAGO AND NEW YORK.

Copyright, 1894, by Dora Russell. Copyright, 1895, by Dora Russell.

A COUNTRY SWEETHEART.

CHAPTER I.

THE NEW HEIR.

In the summer time, from the door of a darkened room, a gray-haired, bent old man had just followed a great surgeon down the wide staircase of Woodlea Hall.

The surgeon looked around when he reached the last steps, and there was kindly pity on his grave face as he met the appealing eyes that were fixed on his.

"I am sorry to say there is no hope, Mr. Temple," he said, in answer to the mute inquiry on his listener's face.

Mr. Temple's bowed gray head bent a little lower when he heard this verdict, and that was all.

"Is he your only son?" asked the surgeon, commiseratingly.

"He is our only child," answered Mr. Temple.

"Ah--that is sad, but there is no doubt football is a dangerous game."

"How--how long will he be spared to us?" now inquired Mr. Temple with quivering lips.

"He will drift away probably during the night, or in the small hours of the morning. He will not regain consciousness; the injury to the base of the brain is too severe."

The great surgeon only stayed a few minutes longer in the grief-stricken household after this, and then was driven away. And when he was gone, with a heavy sigh--almost a moan--Mr. Temple began to ascend the staircase, and on the first landing a lady was standing waiting for him with terrible anxiety written on her pale face.

Mr. Temple looked up when he saw her, and shook his head, and as he did this the lady sprang forward and gripped his hand.

"What did he say?" she asked in a hoarse whisper.

"Come in here, my poor Rachel," he answered gently, and as he spoke he led her forward into a room on the landing, the door of which chanced to be open, and then closed it behind them. "My dear--I grieve very much to say--Sir Henry's opinion is not very favorable."

His voice broke and faltered as he said these words, and a sort of gasping sigh escaped the lady's lips as she listened to them.

"What did he say?" she repeated, with her eyes fixed in a wild stare on Mr. Temple's face.

"He--he said we must prepare--"

"No, no! not to lose him!" cried the lady with a sudden passionate wail. "Phillip, I can not, I will not! He was so bright a few hours ago--so bright and well--my Phil, my boy--and now, now--it will kill me if he dies!"

She flung herself on the floor in a frantic passion of grief before her husband could prevent her, and lay there writhing in a terrible paroxysm of despair, while the gray-haired man beside her bent over her, and tried in vain to comfort or soothe her. She was his wife, but fully twenty years younger than he was; a handsome dark-eyed woman, of some thirty-five years, and the injured boy lying in the darkened room was her only child.

"Who did it?" she suddenly cried, raising herself up. "Who murdered him? Which of the boys?"

"My dear, it is so difficult to tell in a scramble--so difficult to find out."

"I will find out!" went on Mrs. Temple, passionately. "I do not believe it was an accident; someone must have struck him on the head. Oh! my boy, my darling!" she continued, rocking herself to and fro; "the one thing I had to love; the only one that loved me--must, must I lose you, too!"

"It is a terrible blow, Rachel--but--"

"Why not try someone else? Do you hear, Phillip?" said Mrs. Temple, now starting to her feet, and grasping her husband's arm. "Send or telegraph for another doctor at once."

"My dear, it would do no good," answered Mr. Temple, sadly. "You heard what Doctor Brown said; Sir Henry Fairfax is one of the first surgeons in town--and--he said there was no hope."

A wild shriek broke from Mrs. Temple's lips as she heard this fatal verdict. Her agonized grief was indeed pitiful to behold. Again and again she repeated that her boy was the one being that she had to love; was the only one she loved, and the gray-haired old man sighed deeply as he listened to her frantic words.

She never seemed to think of his grief, nor even to remember it. It was her own loss she harped on; her own misery. But Mr. Temple did not reproach her with this. He did not say my heart, too, is broken; the spring of my life is gone. Yet this was so. The poor lad Phillip Temple, drifting away so fast from life, had been the center of all his hopes, the pivot of all his joy. And he, too, was telling himself sadly, as he listened to his wife's moans, that the boy had been the only one who had loved him, or who had cared for his love.

"She never loved me," he thought, looking at the handsome grief-stricken woman before him; and as he did so his memory went back to fifteen years ago; back to the days when he, the squire, had gone wooing to the whitewashed parsonage house, and had won the dark-eyed girl on whom he had set his heart. He had not asked himself then if her heart was his. She seemed to like him; she smiled on him and accepted his presents, and her mother hinted at the advantages of an early wedding-day.

So they were married, and by and by Mr. Temple found out his mistake. She had never loved him, and one morning fell fainting from her chair when she read the news that a soldier cousin had been killed at some distant Indian outpost.

And in the days that followed he learnt the truth. Her cousin had been her lover, but the old hindrance, want of money, had stood between them, and thus Mr. Temple had won his wife. She made very little secret of this to her husband, and did not affect love she could not feel. Her child became her idol, and from the time when the baby boy began first to lisp her name she worshiped him with the whole strength of her passionate, ill-regulated heart.

The boy, however, had been a bond between the husband and wife, and they had got on fairly well together for his sake. They used to talk to each other of his future, and it was a subject equally dear to them both. He was a fine, healthy, clever lad of fourteen when he went out to play football on the fatal day when he was carried back to his father's house insensible. He had somehow fallen, and a rush of boys had swept over him, and when they raised him up he never spoke again. They took him back to Woodlea Hall; the village doctor was sent for in all haste, and at once advised further advice to be telegraphed for. This was done, and Sir Henry Fairfax arrived from town only to pronounce the case to be hopeless.

It was a terrible affair, people said, terrible for the poor mother and for the poor squire, who somehow was the most popular of the two. Country neighbors called at the lodge gates, with commiserating inquiries, while the parents hung over the speechless boy, waiting in terrible anxiety for Sir Henry Fairfax's arrival. He came late in the afternoon, and did not stay long. He carefully examined the unconscious lad, heard what the country doctor had to say, and then told the father the truth.

The boy was dying; the little heir to the broad acres and the old name was about done with earthly things. It had been a beautiful day; the sun had blazed down from a cloudless sky on the wide park, the glowing flower-beds, and the green lawns of Woodlea Hall. It seemed a mockery; outside so bright, inside so full of gloom. Still, until Sir Henry Fairfax's arrival, there had been hope. Doctor Brown, the country doctor, had spoken of "returning consciousness" to the anxious mother. They had watched and waited, however, for that "returning consciousness" in vain. The lad lay white and still, breathing slowly, with closed eyes. He took no notice of his mother's tender words, of her fond appeals. He did not hear them, and his bright eyes were closed to smile no more.

"Rachel, my dear, will you leave him any longer alone?" at last Mr. Temple ventured to say, as his wife wept and moaned, and he laid his hand on her shoulder as he spoke.

She started and looked up.

"Did you say no hope?" she asked, wildly.

"Sir Henry said--" faltered Mr. Temple.

"Then there is none for me--none, none!" went on the wretched woman, in her despair. "Why should I lose everything? Why should God take everything from me? I have been a good woman for Phil's sake, and He is going to take him--all the good that is in me will be buried in his grave!"

"Hush, hush, my poor girl; do not talk thus."

"What do you understand," continued Mrs. Temple, yet more wildly, "of love like mine? You are old--you do not suffer--"

"I do, God knows I do!" cried the unhappy man, and tears rushed into his eyes, and ran down his furrowed cheeks as he spoke.

"When George Hill died, I bore it for Phil's sake," went on Mrs. Temple, regardless, or forgetful, of the useless pain she was inflicting; "and now--and now, my darling, my darling, must I lose you, too?"

"Come to him now, at least," urged Mr. Temple; "you would wish to be with him, would you not, Rachel? There may be some--parting word."

Mrs. Temple moaned aloud.

"You mean before he--"

"Before he leaves us. Come, my poor Rachel, for his sake try to compose yourself."

These words seemed to have some effect on the unhappy mother. She made an effort to be calm, and a few minutes later, leaning on her husband's arm, and tottering as she went, she returned to the bedside of the dying boy.

Those standing round it moved back as she approached it. There were present the village doctor and Mrs. Layton, Mrs. Temple's mother, and the poor lad's nurse. No one spoke. Doctor Brown had already told Sir Henry Fairfax's opinion to the two weeping women, and Mrs. Layton silently put her hand into her daughter's as she neared the bed. But Mrs. Temple shrank from this mark of sympathy. Without a word she fell on her knees and fixed her eyes on the face of the unconscious boy.

No wonder she had loved him. He had inherited her own handsome features, and dark marked brows, and lithe slim form. But his disposition had not been like hers. He lacked her waywardness, her excitability. He had been a sunny-faced, sunny-hearted lad, and to see him lying thus--mute, white, and still--was inexpressibly painful.

They watched him hour after hour. The sun dipped behind the green hills that lay to the west, and slowly the summer daylight began to fade, and still there was no change. Mrs. Layton crept noiselessly out of the room to go down to the vicarage to see after her husband and household, but all the rest remained. The gray-haired father sat at one side of the bed, and at the other the mother knelt. From time to time the doctor felt the small brown wrist that lay outside the coverlet, and the old nurse by the window was praying silently.

But Mrs. Temple breathed no prayer. In her heart was hot revolt and despair. She never took her eyes from her boy's face, and her expression told her anguish. Once the doctor poured her out some wine, but she put it from her with a gesture of loathing.

And so the numbered hours stole on. Presently a new light shone into the room--a soft pale radiancy--and the moonbeams lit the dying face. They fell on it more than an hour, and then a faint change took place in the breathing. The doctor bent down and listened; the father drew a gasping sigh. It was the passing away of the young soul; and a moment or two later they were forced to tell Mrs. Temple that she was childless.

Then the pent-up anguish broke loose. The bereaved mother caught the dead boy in her arms, and called to him by every endearing name to come back to her.

"Come back, my darling, my darling; do not leave me alone!" she shrieked in her despair.

They sent for her mother, but the very presence of Mrs. Layton seemed still further to excite her.

"But for you," she cried, turning on her mother in her frantic grief, "he would never have been born! But for you I would have been with George--George Hill, from whom you parted me!"

It was a most painful scene. Mrs. Layton drew the gray-haired old squire out of the room, and tried to whisper some words of comfort in his ear.

"Grief has made poor Rachel beside herself," she said. "Fancy her talking of George Hill now, when the poor fellow has been dead over ten years. They were children together, you know."

But Mr. Temple made no answer. He knew very well that his wife was speaking the truth, and that his mother-in-law was not. He turned from Mrs. Layton and went into his library, and sat there alone, thinking. The boy's death had changed everything. Mr. Temple was a rich man, for besides his own large property, he had in his youth married for his first wife the daughter and heiress of Sir Richard Devon, whose estates marched with his own. At her death this lady had left everything she possessed to her husband, and thus Mr. Temple was one of the largest land-owners in the country.

The old man sighed when he thought of all this, and covered his face with his hands. He was thinking who would now come after him; thinking of his heir. He knew who it must be. The Woodlea estates had been entailed by his father in the event of his having no children, beyond him. The late Mr. Temple had left two sons, Phillip, the heir, and John, who had gone into the army and died young. But he had married, and left a son, also named John. This John Temple the squire knew was now the heir to Woodlea. He was a man of some thirty years old, and occasionally had visited his uncle, but no great intimacy had existed between them.

John Temple had a fair fortune, and had not sought to increase it. He had been educated as a barrister, but he had never practiced. He had lived a good deal abroad, and led a roving life, it was said, but his uncle knew very little about him. He had had in truth small interest in him. But now all this was changed. His bright young son, his hope and pride, had passed away, and the old squire, sitting with his bowed head, knew that John Temple was his heir.

CHAPTER II.

THE MAYFLOWER.

Three days later they carried young Phillip Temple to his grave, and the new heir came to Woodlea as a mourner. His uncle had written to John Temple to tell him of the sad and untimely death of his son, and John Temple had received the news with a little shrug.

"Poor lad, what a pity, and he was such a fine boy," he said to the friend who was dining with him, when the squire's black-edged letter was placed in his hand.

"But this will make a great difference to you?" answered his friend.

It was then John Temple gave the little shrug.

"It will give me a good many more thousands a year than I have now hundreds," he said, "but that will be about the only difference. The poor lad with his youth would have enjoyed the old man's money more than I shall. I am too old to believe in the pleasures of riches."

"I am not, then," replied the friend enviously; "you can buy anything."

"No," answered John Temple, and his brow darkened.

He was a good-looking man, this new heir of Woodlea, tall and slender, and with a pair of keen gray eyes beneath his dark brows. He looked also fairly-well content with life, and took most things calmly, if not with absolute indifference.

"I have been able to pay my way, and what more does a man want?" he said, presently, as his friend still harped on his new inheritance. "To be in debt is disgusting; I should work hard to keep out of it."

"It is very difficult to keep out of it," was the reply he received.

"You must cut your coat according to your cloth," answered John Temple, smiling. "Had I lived extravagantly I should now have been in debt, but I have not, and therefore I have no duns."

What he said of himself was quite true. He had lived within his income, and was not therefore greatly elated by learning that he would probably soon be a rich man. Perhaps he affected to care less about his change of fortune than he really did. He was cynic enough for this. At all events he accepted his uncle's invitation to be present at his poor young cousin's funeral, and he wrote in becoming and even feeling terms of the sad loss the squire had sustained.

Mr. Temple read this letter with a sigh, but he was not displeased with it. He did not show it to his wife, who was prostrate with grief. Mrs. Temple's condition was indeed truly pitiable. Her one moan was she had no one to love her now, and she refused to be comforted.

"She will be better," said Mrs. Layton to the squire, "when it is all over. Rachel is, and always was, very emotional."

Mrs. Layton meant that her daughter would be better when her young son was in his grave. But Mr. Temple did not consult his mother-in-law on the subject. He fixed the day for the poor lad's burial himself, and he invited the funeral guests. And it was only after John Temple had accepted his invitation that he told Mrs. Layton that he expected his nephew.

Mrs. Layton went home to the vicarage brimful of the news.

"Of course this young man is the heir now," she said to her husband; "but surely Rachel will have the Hall for her life? We must see about this, James."

The Rev. James Layton, an easy-going man, looked up from the composition of his weekly sermon as his wife spoke.

"I dare say it will be all right," he said.

"But it may not be; this young man is sure to marry after the squire's death, and he looks extremely ill and shaken, and I can not have Rachel's home interfered with."

"You are always looking forward," replied the Rev. James, pettishly. "I'm busy, I've my sermon to finish."

"The sermon can wait, and is of no consequence; but Rachel's future is. You must speak to the squire about it at once."

"I consider it would be absolutely indecent, Sarah, to do so at present."

"That's all very fine, but the poor old man may take a fit any day, and then where should we be--with a new madam at the Hall, after all Rachel has gone through?"

"She always seemed right enough till the poor lad died."

"Still, she married an old man, and should therefore have the benefit of it."

"Well, wait until the poor boy is in his grave, at any rate."

"Dilatory as usual! I always said, James, you would never get on, because you are not pushing enough. You do not court the bishop like the other greedy parsons, and just look where you are. At sixty-nine, in a small vicarage like Woodlea, with under four hundred a year! You can not expect me to have patience; and how about poor Rachel? You'll allow this young man, John Temple, to come down to the funeral, and perhaps obtain power over a silly old man, and your own daughter may be left out in the cold! And all because you won't speak a few words, and insist on the Hall being settled on her."

"Speak yourself," said Mr. Layton, impatiently.

"I would at once, only I know he won't listen to me. He's got some stupid grudge into his silly old head, and never consults me about anything. You are the person to do it, and you must do it."

"Well, go away for the present, at any rate."

"Oh, yes, just like you! Wait till young Temple arrives; wait until it is too late, and then you will be satisfied!"

Having thus reproved her husband at the vicarage, Mrs. Layton crossed over to the hall for the purpose of reproving her daughter. And as she entered the wide domains, and looked around at the luxuries and beauties of the place, she naturally felt anxious to keep them in the family.

"Rachel must rouse herself," she mentally reflected, as she ascended the broad staircase. "Now the poor boy is gone, she has lost a bond between herself and the old man, and therefore she must exert herself to keep up her influence."

She thought this again as she walked along the wide, softly-carpeted corridor that led to her daughter's room.

"What a nice house!" she reflected. "No one must come here. No interloper; no new squire and his wife!"

She knew that Mrs. Temple's marriage settlement was everything that was satisfactory. She had seen to that herself when the gray-haired man had gone courting her dark-haired girl. She had taken full advantage of an old wooer's folly, and seen that he paid a heavy price for his bargain. But nothing had been said about the Hall. Then, when the boy was born nothing naturally was said of it. His mother would live, of course, with the young heir. But now the young heir was dead, and some new arrangement must be made.

Mrs. Layton knew she had no easy task before her, when she rapped at the door of her daughter's bedroom. Rachel Layton had been difficult to manage, but Rachel Temple had developed into a very wayward woman. As a rule, she was on fairly good terms with her mother, but she brooked no interference. Mrs. Layton derived many benefits from her connection with the Hall. Her mutton, her butter, her eggs, her vegetables, all came from the same source. The remembrance of this inspirited her. The Hall must remain Rachel's, she told herself, cost her what it would.

It was the day before the poor boy's funeral, and John Temple was expected at Woodlea early on the following morning. There was, therefore, no time to lose. So Mrs. Layton plucked up her courage and entered her daughter's apartment, determined to speak her mind.

Mrs. Temple was standing at one of the windows gazing listlessly out. She could not rest, and her handsome face was lined and drawn with her mental sufferings. She looked years older since her boy's death, and she glanced round as her mother entered the room without speaking.

"Well, my dear," said Mrs. Layton, "how are you feeling now?"

"How can you ask?" answered the unhappy woman, "when everything is ended for me--that is how I feel."

"But, my dear Rachel, this is folly; everything is not ended for you, and you have, I am sure, many years of happy life before you yet."

"Happy life! Very happy life--alone in the world."

"You may not always be alone, Rachel, and I have come here just now, my dear, especially to speak of your future."

"I have no future."

"My dear child, yes; you have had a great loss--"

"No one knows what he was to me!" interrupted Mrs. Temple, passionately, and she began to wander up and down the room wringing her hands as she went. "My darling, my boy, and to think that after to-morrow I shall see him no more--that they will take away from me even what is left!"

"Rachel, has Mr. Temple told you that--his nephew is coming to-morrow?"

"No," replied Mrs. Temple, listlessly.

"He is, then--Mr. John Temple--who, of course, is now Mr. Temple's successor."

"Is he coming so quickly to take my darling's place!" cried Mrs. Temple, with a sudden flash of indignation. "But what matter, what matter!"

"It is a matter, my dear, and it is about this that I wish to speak to you. When you married, the Hall was not included in your settlement, as I now see that it ought to have been, but--we could not foresee your sad loss. Now this young man will succeed Mr. Temple, but he ought not to have the Hall in your lifetime. That must be secured to you, and before this young man arrives I think Mr. Temple ought to be spoken to on the subject, and I should advise you to exert yourself, my dear, and prevent young Mr. Temple gaining an undue influence over your husband."

Mrs. Temple fixed her large dark eyes on her mother's face.

"What are you talking of?" she said.

"I am telling you, my dear Rachel, only you do not seem to attend to what I am saying, that this young man is coming, who is now your husband's heir, and naturally he will try to obtain power over his uncle, which you should not allow. And, as I told you before, this house is not settled on you, therefore--"

"Be silent, mother, be silent!" cried Mrs. Temple with strong indignation, lifting up her hands. "What, when my darling's not gone from it yet--when he is still under the roof--you talk of such things! You always were a wicked, worldly woman, but this is too much--too much!"

Her tone and manner frightened Mrs. Layton. "I only meant, my dear--" she began.

"Go away, leave me alone!" went on Mrs. Temple, and Mrs. Layton thought it best to go.

"She has no common sense," she reflected as she went back to the vicarage. "However, I have done my duty, and whatever happens I am not to blame."

But in spite of this "little disagreement" with her daughter, as she called it, Mrs. Layton did not fail to appear the next day at the Hall. She went early, "as of course I must see after the sad arrangements," she told her husband, "as Rachel is quite incapable of doing so, and I consider Mrs. Borridge, the housekeeper, anything but what she ought to be."

So she interfered in the sad arrangements, and she saw John Temple, the new heir, arrive with jealous eyes. She admitted, however, that he was good-looking, "which makes it worse," she mentally added. She saw also the squire receive him, and introduce him to the funeral guests as "my nephew," with a certain sad emphasis on the words that Mrs. Layton fully understood.

All the gentlemen in the neighborhood had been invited, and nearly all arrived at the Hall to follow poor young Phillip Temple to his grave. The squire of Woodlea was universally respected, and the guests looked at his bowed gray head, and grasped his thin trembling hand with deep sympathy. It was a truly affecting sight as the slim coffin was borne into the churchyard followed by the childless old man. As on the day of the poor lad's death the sun was shining brightly, and in the pretty spot where they laid him, green trees were dappling the green grass.

Groups of the villagers stood around to watch the sad procession, and talk of the dead boy. They had all known him; he had grown up in their midst, and the tragic accident that had ended in his death had occurred in a field close to the churchyard.

John Temple stood by his uncle's side during the service, and he noticed just at its close a girl dressed in white, and wearing white ribbons, step forward and approach the open grave.

She was carrying a large white wreath, and her eyes were full of tears, and she hesitated as if she did not like to go through the group of mourners around the grave. She was close to John Temple, and he turned round and addressed her.

"Do you wish to place that wreath in the grave?" he said, kindly.

"Yes, but I--" faltered the girl.

"Shall I place it for you?" asked John Temple.

"Oh, thank you, if you would," she answered, gratefully.

He took it from her hands, and laid it gently and reverently on his young cousin's coffin. There were many other flowers, and as John Temple placed hers, the girl took courage and went up close to the grave and looked in.

"He was so fond of flowers," she said in a low tone, and her tears fell fast.

"Poor boy," answered John Temple, and then he looked at the girl and wondered who she was.

But the service was over and the mourners turned away, and John went with them. He glanced back and saw that the girl in the white frock was still standing by the grave. Others, too, had now approached it; gone to take a last look at the young heir.

The funeral guests did not return to the Hall, except John Temple, who drove there with his uncle. The squire was deeply affected, and John not unmoved.

"He--he was everything to me," faltered the squire.

"I feel the deepest sympathy for you," answered John Temple, and his words were actually true.

It was a short but dreary drive, and when they reached the Hall the squire asked John Temple to excuse him until dinner time.

"I feel I am unfit company for anyone," he said, "but make yourself quite at home in the house that will be yours some day," he added, with melancholy truth.

Thus John was at liberty to pass the time as best he could. He went to the Hall door, and looked out on the green park. It was a tempting vista. His uncle's words not unnaturally recurred to his mind. So this was his inheritance; this wide wooded domain, this stately mansion house. The son of a younger son, he had been brought up in a very modest home, and he remembered it at this moment. It was certainly a great change, and John Temple thought of it more than once as he walked straight across the park, and finally reached a long country lane scented with meadow-sweet, and its hedges starred with the wild rose.

Temple lit a cigarette, and sat down on a rustic stile. The whole scene was so rural it half-amused John. The hayfield near; the cows standing in another field beneath some trees for shelter from the sun; the distant gurgle of a brook.

This idea had scarcely crossed his mind when he saw advancing down the lane the same girl in the white frock that he had seen by his young cousin's grave. She was gathering the roses from the hedge rows, and placing them in a small basket whenever she saw one that struck her fancy. She was intent on her task, and never saw Temple seated on his stile until she was quite close to him. Thus, he had an opportunity of watching her, as she stretched out her hands to pluck the flowers.

It was a charming face, fresh, young, and beautiful, and Temple was half sorry when, with a little start and a blush, she perceived how near she was to him. He rose and raised his hat, and the girl looked at him half-shyly, and then addressed him.

"It only wants the pretty milkmaid," thought John, with a smile.

"You are the gentleman, are you not," she said, "who so kindly placed my wreath in dear Phil Temple's grave?"

"Yes," answered John Temple, "it was very kind of you to bring one."

"Oh, no," said the girl, quickly, "we knew him so well, you know. He was the dearest boy, and--and his death was so dreadfully sad."

"Most sad, indeed; I am truly sorry for his poor father."

"Oh! it is terrible; terrible for every boy that was playing in the field."

"How did it happen?" asked Temple.

"They were running after the ball, all the boys at Mr. Carson's school, and Phil, they think, fell, and there was a rush of boys, and someone must have struck his head with his foot. No one will say they did, but some one must. My young brother was playing, but no one seems to be able to say how it happened. But he never spoke again; he was unconscious from the first."

"It must have cast quite a gloom over the neighborhood."

"It has been dreadful for everyone; everyone loved him, and to think now--"

"Well, his sufferings are over."

The girl raised her beautiful eyes with a look of surprise to John Temple's face.

"But life is not suffering," she said. "His life was all brightness--but you did not know him?"

"Yes, I did, slightly; he was a fine boy, and I was very sorry indeed to hear of his death. I am his cousin, John Temple."

"I did not know; I heard the squire's nephew was coming--but of course I did not know--"

"And you? Do you live near here?"

"Yes, at Woodside Farm; that white house there, yonder in the fields."

She pointed as she spoke to a long, low house standing some half a mile distant. As she did so John Temple looked again at her lovely face. Never in all his wanderings, he was telling himself, had he seen one half so fair. The coloring and features were alike perfect. Perhaps his gaze was too steadfast, for she dropped her eyes and suddenly turned away.

"I must be going now," she said; "I came to get those roses to make another wreath--good-morning." And she bowed and turned away.

Her manner was so simple and dignified that John Temple felt it would be a liberty to follow her, or try to detain her. Therefore he turned his footsteps once more in the direction of the Hall, and on his way thither he encountered Mr. Layton, the vicar of Woodlea, who had read the service over poor young Phillip's grave.

The vicar had noticed John Temple among the mourners; he was a connection of the family, and he stopped.

"I think I have the pleasure of addressing Mr. John Temple?" he said.

"Yes," answered John, touching his hat.

"I am the vicar here; my daughter married your uncle. Ah--this has been a sad affair."

"Most sad--can you tell me the name of the young lady you must have just met?"

The vicar smiled.

"Ah, that is our village beauty," he said; "they call her the Mayflower."

CHAPTER III.

A SAD FLIRT.

John Temple was too much interested on the subject to be content with such crude information.

"The Mayflower," he repeated, smiling. "What a pretty name for a pretty girl! But I suppose that is not her real name?"

"No, her real name, for I christened her, and so should know, is Margaret Alice Churchill, but she was born in May, and that is how she got her pet name, I suppose."

"She has a lovely face."

"Yes, yes, she is well-favored, and is a good girl, too, I believe--a very good girl. They say young Henderson, of the Grange, wants to marry her, but this may be just gossip."

"And who is he?"

"Oh, he's a well-to-do young man, very well-to-do. His father died about a year ago, and he came into the family property. It's not a large estate, but a snug bit of land, and the old man had saved money."

"Quite an eligible young man then," said John Temple, a little mockingly.

"Yes, Miss Margaret might do worse. And he's a nice lad, too; fond of sport and that kind of thing. But you'll be meeting him, for I suppose now we will often see you at the Hall?"

Mr. Layton looked at John Temple with slight curiosity in his mild face as he said this, for he was remembering the lecture his wife had given him on the subject of the Hall.

"I do not know, I am sure," answered John; "of course nothing has been said yet on any such subject."

"Still, Mr. Temple, you are the direct heir, you know, to the squire after poor young Phil is gone. I always understood the Woodlea property was strictly entailed by the squire's father, on the surviving children of his sons, and you are now the only surviving child, I believe?"

"I believe there was some such arrangement," said John, rather repressively. He considered it too soon to speak of heirs or heirships, and he was getting rather tired also of the vicar's company.

"I think I must be going on my way," he added; "good-day, Mr. Layton," and he touched his hat.

But the vicar was somewhat loth to be shaken off.

"We will meet again at dinner-time; the squire has asked me to dinner; it's a sad occasion, but these things must be."

It was not only a sad occasion, but a very tiresome occasion, John thought, some hours later, when he did meet the vicar again at the squire's table. And not only the vicar, but Mrs. Layton also, who dined unasked at the Hall. She had indeed spent the day there, and was not a woman to know there was a meal going on in her son-in-law's house without joining it. She, therefore, took her daughter's place at the head of the table, also unasked, and talked a good deal to John Temple.

She was a brisk little woman, with a small thin face, and a sharp tongue. She might have been pretty once perhaps, when her eyes were not so hard, if that ever had been. Now she was certainly not pretty, nor sweet with any womanly grace. She had an eager, watchful look, as though always on the alert. She was watching John Temple, as she sat at the squire's table, and talked to him; watching and speculating as to what he would do after the squire was gone.

"How is Mrs. Temple?" asked John, in a low tone, while the vicar was prosing on to the poor squire.

"Poor dear, what can I say?" answered Mrs. Layton; "she was wrapped up in him; yes, wrapped up. I consider it wrong myself, Mr. Temple, to make an idol of anything; all may go, all may go! My dear squire, may I trouble you for a little more of that salmon? It's delicious."

Mrs. Layton got her salmon, and ate her green peas with relish, and all the time went on enlarging about her daughter's grief. She also tried to extract some information from John as to his past life, but here she signally failed. John was reticent and repressive, and probably, as she remarked afterward to her husband, "he had good reason to be."

"And the vicar tells me you met Margaret Churchill to-day," she said, presently. "Well, she's a pretty girl, but I fear a sad flirt, a very sad flirt."

"Pretty girls often get that character," answered John, "because men naturally admire them."

Mrs. Layton shook her head.

"But Margaret really goes too far," she said. "Now there's young Henderson of Stourton Grange, an excellent match for her, and far beyond what she might expect. Yet after letting him run after her for months, and encouraging him in every way, I'm told she's actually refused him."

"She may not like him."

"But then why did she seem to like him, Mr. Temple? Her encouragement was marked, positively marked. And then there's our curate, Mr. Goodall--certainly he is not much in anyway, and has nothing to offer her, but still she flirts with him. I consider it unwomanly, degrading in fact, to make so little of herself as to take up with everyone, yet this is what Margaret Churchill does."

"You are very hard on the pretty Mayflower."

"Yes, now look at that--Mayflower indeed! Such an absurd name. And I'm told she always likes to be called May, but I make a point of addressing her always as Margaret, the name she was christened by."

"If ever I have the privilege I shall call her Miss May."

"It's a privilege you will share with a good many young men, I'm afraid, Mr. Temple. Yes, Margaret Churchill, to my opinion, is a very indiscreet young woman."

"She's very handsome, at all events."

"Yes, in a way; everything depends on taste, you know. James," this was to the footman, "hand me the stewed chicken again. Try this entree, Mr. Temple; it's excellent."

John Temple was exceedingly glad when the dinner was over. Mrs. Layton wearied him to death. She went into small parish details and squabbles, and gave the minutest description of her wrongs.

"A clergyman's wife has many trials, Mr. Temple, but I try to bear them, and it is such a poor parish, too. My husband and I have toiled here for over thirty-nine years, and we barely can live, and certainly the laborer is worthy of his hire."

"Certainly," said John, with a laugh.

"And talking of labor, I do not know what the working classes are coming to," continued Mrs. Layton, with extraordinary rapidity; "I assure you, Mr. Temple, I can not get a man--just a common working man--to plant and dig my little bit of potato ground, under half a crown a day! I've tried a shilling, which I consider fair, eighteen pence, two shillings, all in vain. It's absurd."

Thus Mrs. Layton talked on, and then, after having taken two glasses of port wine, she finally withdrew, "to see after my poor dear," she said, alluding to her daughter. After she was gone John asked leave to go out on the terrace to smoke, and he breathed a sigh of relief when he found himself alone.

The terrace ran round one side of the house, and below it were the gardens. The haze of evening was lying over the glowing flower-beds, and the dew upon the grass. It was all so still; the drone of a late reveler returning from the flowers, the rustle of a bird's wing among the trees, were the only sounds.

Up and down walked John, thinking of many things. "If this had only happened ten years ago," he was reflecting; "happened when I was young."

He did not look very old in the soft light, with the evening breeze stirring the thick brown hair above his brow, for his head was uncovered. A man in his prime; a handsome man, and one well-fitted to please a woman's eyes. Perhaps he knew this, and somehow his mind wandered to the fair-faced girl he had seen and admired in the country lane.

"So she is a little flirt, is she?" he thought, with a smile. "The pretty Mayflower."

The name pleased him almost as much as the girl's beauty had done. She reminded him of the roses he had seen her gather from the hedge. She was so fresh and sweet, he thought, and it amused him to hear of her lovers.

"Of course she has lovers--what girl worth looking at has not?--but I wonder if she has ever loved," he reflected.

By and by he began thinking of another woman, and as he did so he frowned. He began to whistle to distract his thoughts, and then suddenly remembered how lately this had been the house of death. He felt sorry for the poor mother, with her fresh grief, upstairs; sorry for the gray-haired old man.

"I suppose I should go in and talk to him," he said, and he did. He found the squire alone.

The vicar had gone home with his wife, and there was no one in the dining-room but the desolate old man.

John tried to talk to him, but he found it very difficult. When two lives have run in completely different grooves, the conversation is apt to be strained. The squire had always lived in the country, John Temple always in towns. They spoke a little on politics, and John easily perceived his uncle's opinions were opposed to his own. But he did not intrude this on his attention, and it was a subject at least to converse on.

They parted on friendly terms for the night, and the next morning the squire called his nephew into the library, and spoke to him seriously of his change of position.

"It is only right that you should have an allowance out of the estates now, John," he said, "when you will probably so soon inherit them."

"Please do not speak of such a thing," answered John, with an earnest ring in his voice which pleased the squire.

"I must both speak of it and think of it," he said. "My poor boy's death has been a great shock to me, and shocks at my age are not easily thrown off. I wish to feel to you, and treat you now as my heir, and I wish you to be quite open to me as regards your affairs. Like most young men I suppose you have debts?"

"No," smiled John, "I have none."

"I am glad to hear it," answered the squire, "though I was quite prepared to pay them if you had. I also propose to allow you one thousand a year out of the property, and I hope you will look on this house in the future as your home."

"You are most kind and generous, uncle."

"I am simply just; this house, you know, and the Woodlea property are entailed on you. I have other property which came to me through my first poor wife." And here the squire sighed.

"But why speak of things which must be distressing to you so soon?"

"Things of this kind are always best settled--life is so uncertain--look at my dear boy."

"That was a very exceptional case."

"No doubt, but still I wish everything to be arranged between you and me. I am sorry we have not seen more of each other, but it is not too late. For the present you will stay on here, at least for a time?"

"If you wish it, yes."

"I do wish it;" then the squire went into further business details, and John Temple knew that he would be a richer man some day than he had ever dreamed of. The squire had saved out of his large rental, and he had not been communicative to his wife's family as to the real extent of his income. He disliked Mrs. Layton exceedingly, and was barely civil to her for his wife's sake. If she had known the extent of his wealth her encroachments would have been even greater than they were, and Mr. Temple considered he had quite enough of Mrs. Layton as it was.

During this conversation the uncle and nephew were mutually pleased with each other. And after it was over John Temple went out for a stroll, and with a smile at his own folly, turned his footsteps in the direction of the country lane where he had met "the Mayflower."

But no pretty girl was to be seen. The lane somehow looked very empty to John, though the roses were still blooming on the hedge-rows, and the meadow-sweet scenting the air. He therefore walked on and on. He saw a belt of trees in the distance, and he determined to walk until he reached them.

He found when he did so a wooded hillside with a gurgling streamlet at its foot. A rustic narrow bridge spanned the rivulet, and ferns grew on either side of it in great luxuriance. It was a pretty shady spot, with a winding dell on one side of the little bridge. Along this John Temple had proceeded a few yards when he caught a glimpse of something white beneath one of the trees. He looked again and saw it was a girl sitting on a camp-stool reading. He drew nearer; the girl heard his approaching footsteps, even on the mossy turf. She looked up. It was the Mayflower, and John Temple felt he had not had his walk in vain!

He stopped when he reached her, and took off his cloth traveling-cap.

"Forgive me addressing you, Miss Churchill," he said, smilingly; "but I have lost my way."

The Mayflower smiled, too.

"You are a long way from the Hall," she said.

"I wanted a good walk, and now will you tell me where I am?"

"This place is called Fern Dene, and the wood beyond, up the hill there, is called Fern Wood. It is famous for its ferns, and there are some very rare kinds growing about here, and there are also some rare kinds of moths, but I never can bear to catch them."

"No, it's better to let them have their lives in peace."

"Yes, and they look so beautiful fluttering about. But I admit I steal the ferns. This is part of the squire's property, so you must not tell him."

"You would doubtless be arrested as a poacher."

"Not quite so bad as that," laughed the Mayflower; "indeed, I think he knows. Dear Phil Temple," and her expression changed, "often came here with me to help me to collect them, for I have a fernery at Woodside of which I am very proud."

"I wonder if we could find some now?" asked John. "I know something about ferns, and can tell the rare ones."

The Mayflower did not speak; in truth she was considering whether it would be quite proper for her to go fern hunting with a young man of whom she knew so little.

Perhaps John Temple saw, or thought he saw, the reason of her hesitation. He smiled; he looked in her bright fair face, and then he condescended to a subterfuge.

"I feel quite tired with my walk," he said. "I wonder if you would think me rude or lazy if I were to sit down on the turf?"

Still the girl did not answer, but she smiled.

"May I?" asked John, emboldened by the smile.

"The turf is not mine, but the squire's," answered the Mayflower, still smiling; upon which John flung himself on the mossy grass not far from her feet.

"I call this luxury," he said, stretching out his long limbs. "Fern Dene--so this is Fern Dene? Do you often come here, Miss Churchill?"

"Yes, very often; it's a nice walk from home."

"And you read here. May I ask what you were reading when I interrupted you?"

"A novel, of course," answered the Mayflower, with a blush.

"Yes, of course; that is only natural."

The Mayflower looked quickly down at the good-looking brown face raised to hers, as John Temple said this, for something in his tone made her think he was amusing himself at her expense.

"Yes, it is only natural," she answered, with a spirit; "I like to read of lives that I suppose are very often drawn from life."

"With all its tragedies, its comedies, its subterfuges, and its lies--it's always the same old story."

"But there are some lives in which there are no tragedies--nor even comedies?"

"About these, if there be such, there are no stories to tell."

Just at this moment there appeared coming down the hill through the trees behind them the stalwart form of a young man, carrying a gun, and followed by two dogs. He paused a moment when he saw the white dress of the Mayflower, and smiled; but in another moment, perceiving John Temple lying on the grass at her feet, he frowned.

The dogs ran forward and were approaching the Mayflower's camp-stool in the manner of welcome and familiar friends, when their master harshly called them back, and, hearing his voice, the Mayflower looked round just in time to see the young man savagely strike one of the dogs with a whip which he had drawn from his pocket.

The poor beast yelled and shrank back, and the Mayflower rose indignantly, her fair face flushing as she did so.

"Oh, Mr. Henderson, what a shame!" she cried. "What are you striking the poor dog for?"

The young man, on being thus addressed, came forward, and there was a flush on his handsome face also, as he approached the girl. John Temple did not move; he lay looking up at two figures before him.

"Why did you strike Juno?" repeated the Mayflower, as the young man drew near.

He raised his cloth cap as he answered, and his brown eyes fell.

"One must keep them in order," he said, half-sullenly.

"But Juno was doing nothing. Come here, poor Juno; I hate cruelty."

"Yet you sometimes practice it," retorted the young man in a low tone.

He was singularly striking looking. Tall and splendidly formed, with features--though he was as brown as a gypsy--of remarkable regularity. It was indeed impossible not to remark on his personal appearance. The one defect on his face, perhaps, was his mouth, which was sensual looking, though shaded by a thick, crisp, brown mustache. Still, he was a splendid specimen of young manhood, and John Temple, from his vantage ground, mentally, distinctly admitted this. Yet, in spite of all his physical advantages; in spite, also, of being undoubtedly well-dressed, there was a certain countrified look about him which was almost indescribable.

The Mayflower turned her pretty head away when he spoke of her cruelty, and his brown eyes followed this slight movement with unmistakable eagerness. But she made no answering sign of interest. She looked down at John Temple lying on the grass, and he rose as she did so.

"So you are fond of God's dumb creatures?" he said.

"I am very fond of horses and dogs," she answered; "indeed, I think, of all animals."

"And, no doubt, they are fond of you?"

The girl laughed softly and blushed a little, and then stooped down and stroked poor Juno's fawn head, who had once more crept to her side, in spite of her master's lowering looks.

"What a handsome creature!" said John Temple; "and she evidently knows you."

"Oh, yes; we are old friends," answered the Mayflower, and she half glanced at the young man she had called Mr. Henderson as she spoke, but he did not look pleased.

"Perhaps you like new friends better?" he said. "Well, good-morning, Miss Churchill," and once more touching his cap he strode away, whistling for his dogs to follow him.

"Who is the country Adonis?" asked John Temple, smiling.

"Oh, he is called Mr. Tom Henderson of Stourton Grange," replied the Mayflower, demurely.

"Ah!" said John, still smiling. He understood now, he thought, the cause of Mr. Henderson's clouded brow and sullen words.

"He is a handsome fellow, don't you think, Miss Churchill?" he asked.

"People call him good-looking," answered Miss Churchill, and she cast down her eyes a little consciously. "But I don't think he has a nice temper; fancy him striking the poor dog!"

"Perhaps he was jealous because she seemed fond of you."

"That was very foolish then."

"Ah, but jealousy is a devouring demon," said John Temple. "But, of course, you never felt it?"

"Oh, yes, I have!"

"I can not believe it, Miss Churchill, though I am sure you have caused much."

Again that puzzled look stole over the girl's face. She could not help feeling as though she knew Mr. Temple very well, and would like to talk nonsense to him, and yet she was conscious that perhaps she should not.

"Do you know Mrs. Layton, the vicar's wife?" now inquired John Temple, remembering the character she had given Miss Churchill.

"Oh, yes, and she's such a spiteful old woman!"

"She's an awful old woman, I think. She bored me to death last night when she dined at the Hall."

"Did she mention me?" now asked the Mayflower, with a glance of fun in her dark blue eyes.

"Well, to tell the truth, she did," answered John Temple.

"And she abused me, of course?"

"That was impossible."

"Oh, but I know she did if she mentioned me. I am one of her pet aversions. She says all sorts of hard things about me, and because they call me May at home she always addresses me as 'Miss Margaret,' as she thinks it is an ugly name, and I hate it."

"The vicar told me they called you the Mayflower," said John, looking earnestly at the girl's lovely face.

"Oh! that is a foolish name," she answered, with a blush and a smile rippling over her rosy lips.

"I think it is a charming name, and forgive me if I say--"

"Please don't say any nonsense--at least I mean--"

She paused here, and blushed more deeply than before.

"You mean I have not to pay you any compliments? What I was going to say is no compliment, but the simple truth. But I will not tell you even the truth unless you like it."

"I--I do not care for compliments."

"You do not need them."

"That is all right then," smiled the Mayflower. "And--now I must say good-by, Mr. Temple; it is time I was going home."

She put out her little hand quite timidly, and John Temple took it in his own.

"May I see you again sometimes?" he said. "Will you come here again?"

"I--do sometimes come here."

"I shall hope to see you then. Good-by, Miss Churchill."

He took off his cap and stood bare-headed before her, and as with her light feet the Mayflower turned homeward, she was not thinking of her lover, young Henderson, but of the stranger who had just crossed her path.

CHAPTER IV.

THE OLD LOVE AND THE NEW.

After Mr. Tom Henderson had left the Mayflower with John Temple in Fern Dene, he walked onward with a frowning brow and an angry heart. He was in love with the pretty girl he had just seen sitting with another man lying at her feet; in love with her, and jealous of her very words, and moreover he knew who this other man was.

He had seen John Temple at poor young Phil Temple's funeral the day before, and knew therefore that this good-looking, pleasant-tongued man was the new heir of Woodlea.

"And how on earth did Margaret Churchill pick up his acquaintance?" he asked himself, scowlingly. He felt savage at the very thought. He was a hot-tempered man, and had been brought up at home, and always had had very much his own way at Stourton Grange. And now he was master there, and had no small opinion of his own importance.

He knew that in point of family and position he was a good match for Margaret Churchill. Margaret's father was a tenant farmer, and Tom Henderson a land-owner, and he quite appreciated the difference. But the beauty of the neighborhood apparently did not. She did not treat the young squire of Stourton as he expected to be treated, and perhaps this really only added to her attractions in his eyes.

At all events he felt very angry at seeing her with John Temple. He walked on with hasty steps, and never noticed that presently he was followed by a woman. By and by he came to a field of tall uncut corn, which was swaying in the summer breeze. Then she made haste to overtake him. She quickened her steps, she almost ran, and a few moments later she called out his name.

"Tom!" she cried, and young Henderson hearing her voice turned quickly round, and a dusky flush rose to his face as he did so.

"Well, Elsie," he said, stopping and looking by no means well-pleased, "where have you cast up from?"

"Ah! I've followed you ever so far, Tom," panted the girl; "I've been waiting about all the morning trying to see you."

"That was wasting your time then, Elsie."

"No, don't say that, but I could not rest till I saw you. Why did you not come last night, Tom, as you promised?"

"I could not get away; some one came to the Grange."

"Well I've got something to tell you; something that's nearly driven me mad, though I know it's nothing but lies--oh, yes, I know that, Tom."

She looked up in his handsome face as she spoke--the half-averted face--and there was beseeching love and tenderness in her eyes.

"And what is this wonderful thing then, Elsie?" he asked.

"It was Elizabeth Jenkins, and she said--"

"Well, what did she say?"

"I know it's all nonsense, and you mustn't be angry, Tom--but she said you often went to Woodside Farm; that you--were running after Miss Churchill, in fact."

The flush deepened on young Henderson's face.

"Oh! that I was running after her, was I? Well, I haven't caught her yet, Elsie," he said, with an uneasy laugh.

"Oh, don't jest about it, Tom, don't laugh; it was a cruel thing to say--cruel to me."

The young man did not speak; he cast his brown eyes down on the path; he moved the arm restlessly with which he was carrying his gun.

"Of course she just said it from spite--just because she knew--" continued the girl, hesitatingly.

Then Henderson looked up.

"What does she know, Elsie?" he said, glancing at the girl's face.

Her lips quivered and her bosom heaved as he asked the question.

"What everyone must soon know, Tom," she answered; "what you are and must be to me."

An expression of great annoyance contracted Henderson's features.

"And you mean to say you have talked to this woman?" he said, angrily.

"I have not said much," she replied, half-sullenly, "but she knows."

"Then you are a fool for your pains."

He said this roughly enough, and a sudden rush of tears filled the poor girl's eyes as he spoke.

"It can't go on, Tom!" she cried, piteously, "your father's dead now; you know you always promised to marry me when your father died."

"This is folly," muttered Henderson, under his thick mustache.

"What is folly?" asked the girl, sharply, looking up.

"This talk about our marriage--it's an old story, Elsie, and we may as well drop it."

The change in her expression was something terrible, as she listened to these heartless words. She grew deadly pale, and her whole frame trembled.

"Drop it--never!" she repeated, with passionate earnestness. "Tom, if you hate me now you must marry me; I will kill myself or you if you don't."

"It's no good talking folly."

"It's not folly; it's truth, as there is a God above us it is truth! What, after all, after all," and she wrung her hands, "you would go back! But you shall not, Tom! You may think to throw me over because you are tired of me, and take up with another girl, but there are two words to that--I will go to Miss Churchill myself--"

"If you do," interrupted Henderson, with a fierce oath, "I will strike you dead!"

"You can't strike me worse than you've struck me now, but strike me or not, I'll do what I say unless you keep your word."

She stood there defying him, with her eyes gleaming and her hands clenched. She was a handsome woman, of a certain type, with a clear brown skin and thick, coarse black hair. She looked also determined and passionate, and perhaps Henderson was afraid to excite her further. At all events he moderated his tone.

"Well, don't make any more row," he said; "we can talk it over some other time."

"But it must be settled, Tom; I can't wait," she answered.

An evil look came over Tom Henderson's face.

"You are always worrying a man," he said; "there's no such wonderful hurry about it, and there's my mother to consider."

"There's always something to consider; first it was your father, now your mother. But I am to be considered too, I--I and something besides."

Henderson did not speak for a moment; he stood as though irresolute. Again he looked at the excited face before him; at the gleaming dark eyes and full quivering lips, and then he said more soothingly:

"Well, go home now, Elsie, and keep quiet, and we'll see what can be done."

"I am not going to be put off."

"I must consider things, and see what I think best. If you go home now I'll come and have a talk with you to-night at the old place about nine o'clock."

"Will you be sure to come?"

"Yes, I'll be sure. And now, good-by, Elsie; you go your way and I'll go home."

He nodded to her carelessly, and then turned away, and the girl stood looking after him as he went. And there was infinite pain in her expression, infinite distress.

"And he loved me once," she muttered; "he loved me once."

These words seemed like an epitaph on her life's happiness. She knew it was all over, and that the young man to whom she had given so much was weary of her; weary of the frail bondage by which she held him.

And, in truth, never was man more weary. Young Henderson's face was black as night as he strode on after he had left the girl he called Elsie. She was a chain around his neck, an intolerable burden, from which he could see no way to free himself.

And yet he must be free! Margaret Churchill's lovely face rose before him as he passed down the fields of waving corn. He would not give her up, he told himself; he would not let this folly of his almost boyhood come between himself and his fair love.

He remembered the days when he had first known Elsie Wray; the days when he used to ride past the pretty, rather picturesque wayside public house where her father lived, and where the handsome, motherless girl occasionally acted as barmaid.

He was just about nineteen when he had first spoken to her--a handsome, dark-browned lad--and, having been caught in a passing storm, he had taken shelter at the wayside house. Elsie was about his own age--perhaps a year younger--and these two had drifted first into a flirtation, and then, on the girl's part at least, into a deep and passionate love.

It went on for years, always, young Henderson believed, in secret, on account of his father. The squire of Stourton was an irascible old gentleman, and would have allowed "no folly," as he would have called it, between his son and a barmaid. Alas, for the poor girl! The young, ardent, handsome lover came night after night in the gloaming, and the two wandered together in the dewy fields, and sat on the lone hillsides, and talked of the days when they would be free to wed, and when there would be no partings between them any more.

So it went on until, in an evil hour for poor Elsie, young Henderson saw Margaret Churchill's (the Mayflower's) fairer face, and his first love-dream was over. Over for him but not for Elsie Wray, with all its bitter fruits. She could not believe at first that he had changed; it seemed impossible, and she so fond. Then his father died, and her hopes of speedy marriage revived. But there was always some excuse from the once ardent lover. It was too soon after his father's death, his affairs were not settled, and so on.

And now for the first time she had heard from some friend that he went to Woodside Farm, and, naturally, as Miss Churchill was considered the prettiest girl in all the country round, her jealousy was aroused. She, however, little guessed how far her false lover had committed himself with his new love. He had, in fact, asked Margaret Churchill to be his wife, and though she had said him nay, he still held determinately to his purpose.

"No one and nothing shall come between us," he muttered, with gloomy emphasis, with his teeth set hard, as he walked on homeward after his stormy interview with Elsie. And there was a look on his face, a dark, savage look, that boded ill for the poor girl who had loved him too well.

CHAPTER V.

MRS. TEMPLE.

"I can not get that girl's face out of my head," John Temple thought more than once, as he walked back to the Hall. Her beauty had indeed a wonderful charm for him. He had seen and known many pretty women, but to his mind none so fair and sweet as the Mayflower. And he liked to think of her by this name.

"She is just like a flower," he told himself. "Ah! that such a face should ever fade!"

This idea made him more thoughtful. He began to muse on the brief tenure of earthly things. And as he approached the stately house that in all probability would one day be his, he was thinking thus still.

"I may never come here," he thought, looking at the old Hall, with the summer sunshine falling on its gray walls; "never, nor child of mine."

A shadow passed over his face; he struck impatiently with his walking stick at a tall thistle growing by the wayside, and there was a cloud still on his brow as he entered the hall, and went up the broad staircase that led to the bedroom appropriated to his use.

As he passed down one of the corridors, a tall lady in black suddenly opened one of the doors and appeared before him. She was very pale, and her dark eyes were gleaming as though she were laboring under strong mental excitement.

She looked at John Temple, and then came out on the corridor and confronted him.

"So," she said, "you have come to take my boy's place?"

Then John knew at once who she was. This was his uncle's wife, the bereaved mother, who had lost her only child. He bowed low, and a look of pity came into his gray eyes.

"I have felt very much," he said, "for your great grief."

"It has benefited you, at any rate," she answered, bitterly.

"I can not feel it a benefit at such a cost."

She looked at him keenly as he said this, and then her faced softened.

"You can not tell what he was to me," she murmured in a broken voice; "my only one, my only one!"

A sudden passion of tears here came to her relief. Her bosom heaved and her whole form was convulsed, and John Temple naturally felt exceedingly disconcerted. He tried to say some consoling words; he endeavored to take one of her trembling hands. But the sound of her sobs soon attracted the attention of someone within the bedroom from which she had come out. A respectable maid appeared and endeavored to persuade her to return.

"Oh, madam! do not give way so," she said; "I was sure it was a pity you should see--this gentleman so soon. But she would see you, sir," she added, looking at John Temple.

"If my presence distresses you," said John, courteously, looking pityingly at the weeping woman, "I shall leave the Hall at once."

"What matter is it, what matter is it!" moaned Mrs. Temple; "nothing matters to me now!"

With this she turned away and went back into the bedroom, and the maid hastily closed the door after her, and John saw her no more. But the incident affected him; her grief was evidently so deep and heartrending; her bitter words to him only the natural outpouring of her troubled heart.

"Poor woman," thought John, and he said nothing to his uncle of this meeting when they dined together in the evening.

The squire again spoke to John of the property and his tenants.

"I have improved some of the farm holdings very much during the last few years," he said; "at Woodside Farm especially the whole of the outbuildings have been renewed."

"Ah," said John, interested, "at Woodside Farm?"

"Yes, that is one of the best farms on the property, and is let to a very respectable man named Churchill. Suppose we walk over to-morrow morning, and I will show you the place?"

John, nothing loath, at once assented.

"The house is old and somewhat picturesque," continued the squire, "and now that the outbuildings are in such good order, I consider Woodside a sort of model place."

John expressed himself desirous of seeing it, and he doubtless was. He had not forgotten that Woodside was the Mayflower's home, and he wished again to look on her fair face.

"There can be no harm in it," he thought; "it is a very innocent pleasure indeed to admire a pretty girl."

Accordingly at breakfast the next morning he reminded the squire of his proposition of the night before.

"Didn't you say, sir," he said, "that we had to go over and see some model farm or other this morning?"

"Yes, to be sure, Woodside Farm," answered the squire, "but it had gone out of my head, as things sometimes do now. I am glad you reminded me of it."

The uncle and nephew accordingly started together almost immediately breakfast was over.

"We will get there, I think, before Churchill gets away among his fields," said the squire. "I should like you to see him, for I believe him to be a highly respectable man."

It was a bright, fresh morning, and John Temple enjoyed the walk. The waving mazes of uncut corn; the hedge-rows scented with the meadow-sweet; the cattle standing under the trees, made to his mind a pleasant picture.

"After all, the country is charming," he said, raising his head as though more freely to inhale the air, and looking round at the green and fertile landscape.

"Do you think you would not tire of it?" asked the old man by his side, lifting his sad eyes and looking steadfastly at his nephew's good-looking face. He was wondering what his life had been; how the last decade of his thirty years had passed. Not in riotous living he told himself, for John Temple's features bore no marks of dissipation nor sin. His eyes were clear and resolute, his whole bearing that of a man who had led at least a fairly good life.

"He looks honest," thought the squire, and then he sighed, thinking of his dead boy, and all the fond hopes which lay buried in his untimely grave.

"I might tire of it," answered John, smiling in reply to his uncle's question, "if I never had any change, for I think we all want change. It is human nature, part of our heritage, to desire it."

Again the old man sighed.

"You must marry now, John," he said, and as he spoke a flush rose to his nephew's face.

"I think not," he answered.

"You will think differently I hope, some day," continued the squire. "But here we are at Woodside; it is a pretty spot."

It was indeed a pretty spot; a long, low, white house, standing amid a large old-fashioned garden, with trim box-borders, and fruit trees laden with their ripening crops. They approached the house from the front, but at the rear the squire pointed out with some pardonable pride the new and expensive outbuildings.

"I wish every farm on the property was in such good order," he said. "But we will go into the garden, and I dare say will find the farmer somewhere about, or perhaps his daughter can tell us where he is."

As he spoke the squire opened the garden gate and passed down the walks, accompanied by John Temple and followed by two dogs. A little summer house stood on the path, and a moment later a pretty scrimmage ensued. A very handsome gray kitten was disporting itself at the entrance of the summer house, and at the sight of the avowed enemies of its race, the kitten prepared for battle. With tail erected and every hair on end, it stood to receive the charge it evidently expected. The dogs saw it, and with vicious yells ran forward, and the brave kitten's moments had been numbered had not its mistress with a cry sprang forward from the interior of the summer house and caught it to her breast. The squire and John called back the dogs; the Mayflower protected her kitten, and then stood smiling and blushing to receive her visitors at the entrance of the summer house.

"Oh, Mr. Temple, your dogs frightened me so!" she said, as the squire offered her his hand.

"I am very sorry," he answered, "but they have not touched your kitten, have they?"

"In another instant they would," smiled the Mayflower, holding her pet tightly in her arms.

"What a pretty creature it is," said John Temple, now stroking the kitten's striped head, whose large eyes were wide open with terror.

"Yes, isn't he a beauty?" answered the Mayflower. "Poor Jacky! and would the naughty dogs have eaten you?"

Jacky looked as if he decidedly thought that they would, and clung to his mistress' white frock, who soothed and comforted him. The Mayflower certainly was a lovely creature as she stood thus, with her fair head uncovered. She had been sewing in the summer house; trimming a white straw hat, and ribbons and flowers lay strewn about, and as a man of taste John Temple found it impossible not to admire so pretty a picture.

"Is your father in the house?" now asked the squire.

"He was in the garden five minutes ago, looking at the apple trees," replied the Mayflower. "Shall I call him, Mr. Temple?"

But at this moment Mr. Churchill, the farmer, was seen advancing toward them, as he had heard in another part of the garden the squire and John Temple calling back their dogs, and now came to see what was the matter. He took off his low-crowned hat when he recognized the squire, but Mr. Temple held out his thin hand to his favorite tenant.

"Well, Mr. Churchill, how are you?" he said. "I have brought my nephew to see you; my nephew--and now my heir."

His voice faltered a little as he said the last few words, and a look of respectful sympathy passed over the farmer's brown face.

"Glad to make your acquaintance, sir," he said, looking at John Temple with a pair of very intelligent gray eyes.

Altogether he was a good-looking man, and was, moreover, an excellent farmer. He had gone with the times, and instead of grumbling at the price of corn and foreign competition, grew on his land the crops he found to sell best. He was a great breeder of horses also, and his stud was quite a famous one. He was also a keen man at a bargain, and prosperous. He had married a lady in a superior social position to himself, whom he had won by his good-looking face, and he had given his only daughter Margaret Alice Churchill (the Mayflower) an excellent education. Mrs. Churchill had died two years ago, but as yet he had taken no second wife, so May, as she was always called at the farm, was the mistress of the house.

He had two other children, both schoolboys, and Willie Churchill (the second boy) had been one of the players in the fatal game of football when poor Phil Temple, the little heir of Woodlea, had met his death. The squire knew this fact, but no particular blame had been laid on the boy. A rush had taken place, and the little heir had fallen, and it was said to be impossible to tell who had given the actual kick or blow that had destroyed Phil Temple's life.

"I think it will interest my nephew to have a look at your stud," continued the squire; "he's lived mostly in towns, and knows nothing of farming, I dare say, but horses interest nearly all men."

"To be sure," answered Mr. Churchill. "But won't you come in, gentlemen, and rest awhile first, and have a glass of claret, or a taste of our home-brew or cider?"