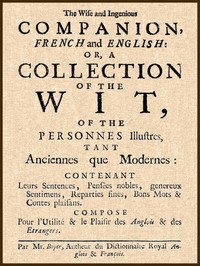

Read and listen to the book The Wise and Ingenious Companion, French and English;: or, A Collection of the Wit of the Illustrious Persons, Both Ancient and Modern by Boyer, Abel.

Audiobook: The Wise and Ingenious Companion, French and English;: or, A Collection of the Wit of the Illustrious Persons, Both Ancient and Modern by Boyer, Abel

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Wise and Ingenious Companion, French and English; Abel Boyer. 1667-1729

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Wise and Ingenious Companion, French and English; Abel Boyer. 1667-1729 or, A Collection of the Wit of the Illustrious Persons, Both Ancient and Modern

Author: Abel Boyer

Release Date: April 7, 2017 [EBook #54498]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WISE AND INGENIOUS COMPANION ***

Produced by Turgut Dincer, RichardW, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

The Wise and Ingenious COMPANION, FRENCH and ENGLISH:

OR,

A COLLECTION OF THE WIT, OF THE Illustrious PERSONS, BOTH Ancient and Modern:

CONTAINING

Their wise Sayings, noble Sentiments, witty Repartees, Jests and pleasant Stories.

CALCULATED

For the Improvement and Pleasure of the English and Foreigners.

By Mr. Boyer, Author of the Royal Dictionary.

Omne tulit Punctum qui miscuit utile Dulci. Horat.

London. Printed by G.C. for Tho. Newborough, at the Golden-ball in St. Paul’s Church-yard, and J. Nicholson at the Kings Armes in Little Britain. 1700.

LE COMPAGNON Sage & Ingenieux, ANGLOIS & FRANÇOIS.

OU

Recueil de L’ESPRIT, DES PERSONNES Illustres, TANT Anciennes que Modernes:

CONTENANT

Leurs Sentences, Pensées nobles, genereux Sentimens, Reparties fines, Bons Mots & Contes plaisans.

COMPOSE

Pour l’Utilité & le Plaisir des Anglois & des Etrangers.

Par Mr. Boyer, Autheur du Dictionnaire Royal Anglois & François.

Omne tulit punctum qui miscuit utile dulci. Horat.

A Londres. Chez Tho. Newborough à la boule d’Or, au Cimetiere de S. Paul; Et John Nicholson aux Armes du Roy, dans la petite Bretagne, 1700.

A Prefatory

INTRODUCTION;

CONCERNING

The Excellency, Nature and Use of wise Sayings witty Repartees, Jests, and pleasant Stories.

Sentences, witty Repartees and Jests, have ever been esteem’d by all civilized Nations: The ancient Greeks and Romans have shewn what account they made of them, by their care of Collecting and Quoting them. Julius Cesar made a Collection of the Jests of his Contemporaries; the famous Historian Plutarch is very exact in recording all those of the illustrious Men of whom he writes the Lives: Wherein he has been imitated by Diogenes Laertius, in his lives of the Philosophers; and among the Moderns, my Lord Bacon, Guichardin, and several others have enrich’d their Writings with them.

These Testimonies carry so much weight with them, that we cannot but join our Approbation with that of so many illustrious Persons: The only Question is how to make a good Choice, and not confound true Wit and Sense with abundance of low Thoughts, and dull, and vulgar Jests which are imposed upon the World; and this I have proposed to do in the following Collection.

INTRODUCTION

En forme de

PREFACE,

TOUCHANT

L’Excellence, la Nature, & l’Usage des Sentences, Reparties fines, Bons Mots, & Contes Plaisans.

Les Sentences, les Reparties fines, & les Bons Mots ont toujours été estimez de toutes les Nations policées: Les anciens Grecs & Romains ont fait voir le cas qu’ils en faisoient, par le soin qu’ils ont eu de les recueillir & de les citer. Jules Cesar fit un Recueil des Bons Monts de ses Contemporains; le celebre Historien Plutarque est fort exact à rapporter tous ceux des Hommes illustres dont il écrit les Vies; en quoi il a été imité par Diogene Laërce dans les Vies des Philosophes; & parmi les Modernes mylord Bacon, Guicharchin, & plusieurs autres en ont enrichi leurs Ecrits.

Ces Témoignages sont d’un si grand Poids, que nous ne saurions nous dispenser de joindre nôtre approbation à celle de tant d’illustres Personnes: Il s’agit seulement de faire un bon choix, & de ne pas confondre l’Esprit & le bon Sens avec quantité de Pensées basses, & de Plaisanteries froides & vulgaires qui se debitent dans le monde, & c’est ce que je me suis proposé de faire dans ce Recueil.

The Ancients under the names of Apophthegms, comprehended what we call wise Sayings, generous and noble Sentiments, Jests and witty Repartees: However, according to our Notions, the Apophthegm thus differs from a Jest or Repartee, that the first is generally Grave and Instructive; whereas Jests and Repartees instruct us and make us merry at once; nay, sometimes these are meerly diverting, and sometimes sharp and Satirical.

The French call Bons Mots all those witty Sayings and ingenious Replies which are the result of a true Judgment, and of a happy and quick Imagination.

Now the first and most certain Rule to know a true Jest from a false Thought, is that it may be translated into another Language, without losing any thing of its Sense and Pleasantness; for then it is certain that it runs upon the Thing expressed in it, and not upon a Pun or Quibble.

Les Anciens sous le nom d’Apophthegmes comprenoient ce que nous appellons Sentences, Sentimens nobles & genereux, Bons Mots, & Reparties fines: Cependant, selon nos Idées, l’Apophthegme differe d’un Bon Mot, ou d’une Repartie, en ce que le premier est ordinairement grave & instructif, au lieu que les Bons Mots & les Reparties nous instruisent & nous rejouïssent en même tems; quelquefois même ceux-ci sont purement divertissants, & quelquefois piquans & satiriques.

Les François appellent Bons Mots, toutes ces Sentences & Reparties ingenieuses qui partent d’un bon Jugement & d’une Imagination prompte & heureuse.

La premiere & la plus certaine Regle pour distinguer un veritable Bon Mot d’avec une fausse Pensée, est qu’il puisse être traduit en une autre Langue, sans rien perdre de sa justesse & de son agrément; car alors il est certain qu’il roule sur la chose qui y est exprimée, & non pas sur une Pointe, ou sur une Rencontre.

Puns and Quibbles are what we call playing upon Words, or Equivocations; they are known by this, that being turned into another Language, they loose that resemblance of Sound wherein their subtilty consists; and as they affect the Ear more than the Mind, we must take care not to mistake them for true Jests. The pretended Beauty of Equivocations is only owing to Chance, which makes one and the same Word to signify several Things, and therefore their double Application is generally forc’d; but suppose it were true, a Jest is still imperfect when it runs upon the Expression, and not upon the Thought. I confess an Equivocation may be allow’d of when it offers two different Ideas to our Mind, one of which is in a Proper, and the other in a Figurative Sense. But as for those miserable Puns and Quibbles, which are nothing but an empty gingle of Words, the French have branded them with the infamous Name of Turlupinades; and they ought to be banished the Conversation of polite and well-bred Persons, as only fit to entertain the vulgar Sort.

Les Pointes & les Rencontres sont ce qu’on appelle des jeux de Mots ou des Equivoques; on les connoit par ceci, c’est qu’étant traduites en une autre Langue, elles perdent cette ressemblance de son dans laquelle leur subtilité consiste; & comme elles regardent plus l’Oreille que l’Esprit, nous devons prendre garde de ne pas les confondre avec les veritables Bons Mots. La pretenduë beauté des Equivoques n’est qu’un effet du hazard, qui fait qu’un même Mot signifie plusieurs choses; ainsi leur double application est presque toûjours forcée; mais supposé qu’elle fut juste, le Bon Mot est imparfait lors qu’il ne roule que sur l’Expression, & non par sur la Pensée. J’avouë que l’Equivoque peut être supportable lors qu’elle offre deux Idées differentes à nôtre Esprit, dont l’une est dans le sens propre & l’autre dans le sens Figuré: Mais pour ce qui est de ces mechantes Pointes, qui ne sont qu’un vain son de Mots, les François les ont notées d’infamie sous le nom de Turlupinades, & elles doivent être bannies de la Conversation des gens polis & bien élevez, n’étant propres qu’à divertir le Vulgaire.

Jests and wity Repartees have ever been more frequent among the ancient Grecians than any other Nations: Which may be ascribed, first to the quickness of their Wit, their deep Learning, and good Education; secondly, to the constitution of their Government; for living for the most part in Common-wealths, they were not constrained in their Fancy by the Respect due to Sovereigns, and those whom they make sharers of their Authority in Monarchical States; wherein the different degrees establish’d among Men, do often keep Inferiours from speaking their Thoughts about the Ridiculum of those above them.

Les Bons Mots & les Reparties fines ont été plus frequentes parmi les anciens Grecs que parmi les autres Peuples: Ce que l’on peut attribuer, premierement à la vivacité de leur Esprit, à leur profond sçavoir, & à leur bonne Education; secondement: Car la pluspart vivant dans des Republipues leur Esprit n’etoit pas retenu par le respect deu aux Souverains, & à ceux aux quels ils font part de leur Autorité dans les Etats Monarchiques; où les divers degrez qu’on y a etablis parmi les Hommes, empêchent souvent les inferieurs de dire ce qu’il pensent sur le Ridicule de ceux qui sont au dessus d’eux.

We may draw a double advantage from true Jests, for besides that they serve to make us merry, and revive now and then a fainting Conversation: Several of them are full of good and wholesom Instructions, applicable to the different Exigencies of Life, both in a publick and private Fortune.

On peut tirer un double avantage des Bons Mots, car outre qu’ils servent à nous divertir, & à ranimer une Conversation languissante, il y en a plusieurs qui sont remplis de belles Instructions, qu’on peut appliquer aux differents Etats de la Vie, dans une Fortune publique ou privée.

As for Stories they differ from Jests, in that they express their Subject in its full Latitude, and generally leave nothing to be guest at, as Jests do; they are sometimes divertingly Instructive; but their chief aim is to make the Hearers merry by relating sometimes a concurrence of Comical Accidents; sometimes a piece of Simplicity or Ignorance, and sometimes Malicious Tricks that have been put upon any one, to make Sport for others: In all these we must use the same Caution as we have mentioned about Jests, that is, we must take care not to confound good Stories with many pieces of low Buffoonry, which tickle mean and vulgar Ears by their smutiness, dawb’d over with paltry Equivocations.

Pour ce qui est des Contes, ils different des Bons Mots en ce qu’ils exposent leur sujet dans toute son étenduë, & ne laissent d’ordinaire rien à deviner comme font les Bons Mots. Ils instruisent quelquefois en divertissant, mais leur principal but n’est que de rejouïr leurs Auditeurs en rapportant tantôt quelque rencontre d’Accidens plaisans; tantôt quelque naïveté ou quelque Ignorance; & quelquefois des Tours malicieux, dont on s’est servi pour divertir les autres aux depens de quelqu’un. Dans les Contes il faut user de la même precaution dont nous avons parlé touchant les Bons Mots, c’est à dire, nous devons avoir soin de ne pas confondre les bons Contes, avec plusieurs Bouffonneries basses, qui chatouillent les Oreilles du Peuple par leurs ordures, cachées sous de méchantes Equivoques.

Now the use a Gentleman ought to make of Jests and Stories is, never to quote them but when they come pat and à-propos to the Subject and before those who are disposed to hear and be merry with them; without courting the occasion of being thought a pleasant and jocose Man, for Persons of a nice discernment will presently take notice of those nauseous Affectations: And as the judicious La Bruyere has it: That Man who endeavours to make us Merry, seldom makes himself to be esteem’d.

L’Usage qu’un honnête homme doit faire des Bons Mots & des Contes, est de ne les citer que lors qu’il viennent à propos & naturellement au sujet, & en presence de ceux qui sont disposez à les entendre & à s’en divertir; sans rechercher l’occasion de faire le plaisant & l’enjoüé, car les gens d’un discernement delicat connoissent d’abord ces sortes d’Affectations; & selon le judicieux Mr. de la Bruyere: Il n’est pas ordinaire que celui qui fait rire, se fasse estimer.

We must also observe never to usher in Jests or Stories with formal Commendations, which will prevent our hearers from being agreeably surpriz’d; for ’tis by this surprise that the Pleasure they give is principally excited. Likewise when we begin to tell them, we must not begin to laugh our selves, if we intend to make the Company laugh; for those who promised us Mirth before-hand, are seldom so good as their Words; and how silly and ridiculous does that Man look who laughs by himself, at a cold and thread-bare Jest, whilst the rest can hardly force a Smile to keep him in Countenance? Lastly, we must avoid telling a Jest or Story several times over to the same Persons, an Impertinence which makes the Conversation of old People so very distateful.

Il faut aussi observer de ne pas introduire les Contes & les Bons Mots par des loüanges étudiées, qui empêchent nos Auditeurs d’être agréablement surpris; parce que c’est par cette surprise que le plaisir qu’ils excitent est principalement causé. Il faut encore que lors que nous les racontons nous n’en rions pas les premiers, si nous voulons faire rire la Compagnie; Car il arrive souvent que ceux qui nous ont assuré qu’ils vont nous faire rire, ne tiennent pas leurs promesses; & rien n’est si sot ni si ridicule qu’un homme qui rit seul d’une Pensée froide & usée, pendant que les autres tâchent en vain de soûrire pour l’empêcher de perdre Contenance. Enfin, il faut éviter l’inconvenient de dire un Conte ou un Bon Mot plusieurs fois aux mêmes Personnes, ce qui est un Ridicule qui rend la Conversation des vieilles gens si desagréable.

Before I make an end of this Introduction, I shall obviate an Objection which some supercilious Criticks will be apt to make against this Work, viz. That most of these Apophthegms, Jests, Repartees and Stories, are already known to Persons of good Education, and to Men of Learning: To which I answer, That granting this to be true, yet ’tis hoped they may be glad to find them here again, just as we are pleased to hear a fine Tune over and over, provided it be well Sung: But besides, this Collection is so vastly Rich, that it is hard, if not impossible, for any single Reader to know all it contains and not be either instructed or diverted by some thing that will be new to him. To which I must add, That my chief Design in this Collection is to facilitate the Learning of the French Tongue to the English; and that of the English Language to Foreigners, and upon that score I have taken particular care to make both Languages answer one another, as near as their different Idioms would allow.

Avant que de finir cette Introduction, je previendrai une Objection que quelques Critiques de mauvaise humeur pourront faire contre cét Ouvrage, qui est, que la pluspart de ces Apophthegmes, Bons Mots, Reparties & Contes sont deja seus par les Personnes bien élevées, & par les gens de Lettres; à quoi je repons, que quand cela seroit, on espere pourtant qu’ils seront bien-aise de les retrouver ici, de même qu’on entend avec plaisir un bel Air, quoi qu’on fait deja entendu, pourveu qu’il soit bien chanté. Dailleurs ce Recueil est si grand & si riche, qu’il est difficile, pour ne pas dire impossible qu’un même Lecteur sache tout ce qu’il contient, & qu’il ne soit instruit ou diverti par quelque chose qui aura pour lui la grace de la nouveautê. A quoi je dois ajoûter que mon dessein principal dans ce Recueil est de rendre la Langue Françoise facile à apprendre aux Anglois, & l’Angloise aux Etrangers; & c’est pour cela que je me suis attaché avec soin â faire repondre ces deux Langues l’une à l’autre autant que leurs differens Idiomes l’ont pû permettre.

THE Apophthegms OF THE ANCIENTS, BEING

Their wise Sayings, fine Thoughts, noble Sentiments, Jests and witty Repartees, &c.

1.

A Rich Man of Athens desired the Philosopher Aristippus to tell him how much he must give him to instruct his Son: Aristippus ask’d him a Thousand Drachms. How! said the Athenian, I could purchase a Slave for that Money: Do so, answer’d Aristipus, and thou shalt have two; giving him to understand, that his Son would have the Vices of a Slave, if he did not bestow a liberal Education upon him.

LES Apophthegmes DES ANCIENS, C’est à dire

Leurs Sentences, belles Pensees, nobles Sentimens, bons Mots, & Reparties fines, &c.

1

Un Riche Athenien pria le Philosophe Aristippe de lui dire ce qu’il desiroit pour instruire son Fils: Aristippe lui demanda mille Drachmes. Comment, dit l’Athenien, j’acheterois un Esclave de cét Argent là; Achetes en un, lui répondit Aristippe, & tu en auras deux; lui faisant entendre que son Fils auroit les defauts d’un Esclave, s’il ne faisoit pas la depense nécessaire pour le bien élever.

2

The famous Philosopher Anacharsis was a Scythian by Birth and a Grecian who had no other Merit than that of being born in Greece, looking upon him with Envy, reproached him with the Barbarousness of his Country; I confess, reply’d Anacharsis, that my Country is a Shame to me; but thou art the Shame of thy Country. This Saying may be very well applied to those shallow Wits who despise Strangers, meerly because they are Strangers; not considering that Learning, Wit and Merit, are of all Countries.

Le fameux Philosophe Anacharsis ètoit Scythe, & un Grec qui n’avoit d’autre Merite que d’être né en Grece, le regardant avec envie, lui reprochoit la barbarie de son Païs: J’avouë, lui repliqua Anacharsis, que mon Pays me fait honte, mais tu fais honte à ton Pays. Ce mot peut être fort bien appliqué à ces petits Esprits qui méprisent les Etrangers seulement parce qu’ils sont Etrangers, sans considerer que le Sçavoir, l’Esprit & le Merite sont de tout Pays.

3

When Theopompus was King of Sparta, one was saying in his Presence, that it now went well with their City, because their King had learn’d how to Govern: To which the King very prudently Replied, That it rather came to pass, because their People had learn’d to Obey; intimating that Popular Cities are most injurious to themselves, by their factious Disobedience; which while they are addicted to, they are not easily well governed by the best of Magistrates.

Lors que Theopompus ètoit Roy de Sparte, quelqu’un dit en sa presence, que leurs Ville ètoit florissante, parce que leurs Rois avoient appris à gouverner, à quoi le Roy repondit fort sagement, Que cela venoit plûtôt de ce que le Peuple avoit appris à obeïr; donnant à entendre que les Villes où la Populace a du credit, se font beaucoup de tort par leurs Factions & leur desobeïssance, & qu’alors il est difficile, même aux meilleurs Magistrats de les bien gouverner.

4

Dionysius the elder, Tyrant of Syracuse, reproving his Son, for that he had forcibly violated the Chastity of one of the Citizens Wives, asked him amongst other Things, if he had ever heard that any such thing had been done by him; No, said the Son, but that was because you was not Son to a King: Neither, said Dionysius, will you ever be a Father to one, unless you give over such Pranks as these. The event proved the truth of what he said; for when this young Man succeeded his Father, he was expelled the Kingdom of Syracuse for his ill Behaviour and manner of Life.

Denys le vieux, Tyran de Syracuse, grondant son Fils de ce qu’il avoit violé la Chasteté de la Femme d’un des Bourgeois, lui demanda entr’autres choses, s’il avoit jamais entendu dire, qu’il eut fait de pareilles Actions; Non, lui dit le Fils, mais c’est parce que vous n’ètiez pas Fils de Roy: Tu n’en seras jamais Pere, lui dit Denys, si tu fais plus de ces Folies. L’evenement justifia la verité de ce qu’il disoit; car ce jeune Homme ayant succedé à son Pere, il fut chassé du Royaume de Syracuse à cause de sa méchante Conduite & de sa mauvaise Vie.

5

King Antigonus came to visit Antagoras a learned Man, whom he found in his Tent busied in the Cooking of Congers, Do you think, said Antigonus, that Homer at such time as he wrote the glorious Actions of Agamemnon was boiling of Congers? And do you think, said the other, that Agamemnon when he did those great Actions, was wont to concern himself whether any Man in his Camp boiled Congers or not,

Le Roy Antigonus alla voir Antagoras, Homme savant, lequel il trouva dans sa Tente occupé à apprêter des Congres; Croyez vous, lui dit Antigonus, qu’Homere fit bouillir des Congres lors qu’il écrivoit les glorieuses Actions d’Agamemnon? Et pensez vous, lui dit l’autre, que lors qu’Agamemnon faisoit ces belles Actions, il se mît en peine si quelqu’un dans son Camp faisoit bouillir des Congres ou non?

6

Socrates was asked, why he endured his Wifes Brawling; says he, Why do you suffer your Geese to gaggle? because, answered one, they lay us Eggs; and my Wife brings me Children, said he.

On demanda à Socrate pourquoy il enduroit les Criailleries de sa Femme, & vous, dit il, Pourquoy souffrez vous le bruit de vos Oyes? Parce, repondit quelqu’un, qu’elles nous pondent des Oeufs; & bien, dit il, & ma Femme me fait des Enfans.

7

Apelles the famous Painter, drew the Picture of Alexander the Great on Horse-back, and presented it to him; but Alexander not praising it as so excellent a Piece deserved, Apelles desired a living Horse might be brought, who seeing the Picture, fell to pawing and neighing, taking it to be a real one; whereupon Apelles told him, his Horse understood Painting better than himself.

Apelles le fameux Peintre, fit le Portrait d’Alexandre le Grand à Cheval, & le lui presenta, mais comme Alexandre ne loüoit pas assez un si excellent Ouvrage, Apelles demanda qu’on fit venir un Cheval en Vie, lequel à la veuë du portrait se mit à trepigner des Pieds, & à hennir, le prenant pour une realité; surquoy Apelles, lui dit, que son Cheval s’entendoit mieux en Peinture que lui.

8

Virgil, the famous Poet, was much in favour thro’ his great Wit and Learning with Augustus, insomuch that he daily received his Bread from him; Augustus one Day knowing his deep Discretion, ask’d him privately, If he could guess what was his Father; to which he replied, Truly Sir, I do verily believe he was a Baker, a Baker, and why so? says Augustus; because says Virgil, you always reward me with Bread, which Answer so well pleased the Emperour, that he rewarded him afterwards with Money.

Le fameux Poëte Virgile s’ètoit si bien acquis les bonnes Graces d’Auguste par son Savoir & par son Esprit, qu’il en recevoit son Pain ordinaire; Auguste connoissant la profondeur de son jugement, lui demanda un jour en particulier, s’il pouvoit deviner ce qu’ètoit son Pere? Seigneur, lui repliqua-t-il, je crois fermement qu’il ètoit Boulenger; Boulenger, & pourquoy cela, lui dit Auguste; parce, dit Virgile, que vous me recompensez toûjours en Pain. Cette Réponse plût si fort à l’Empereur, que dans la suite il le recompensa en Argent,

9

Alexander the Great, having defeated the Army of Darius King of Persia, Darius sued to him for Peace, and proffered him one half of Asia, with ten thousand Talents. Parmenio, one of his Favourites, charm’d with so advantageous a Proposal, Sir, said he to his Master, I vow were I Alexander, I would gladly accept these offers; and so would I, answered Alexander, if I was Parmenio.

Alexandre le Grand ayant remporté la Victoire sur l’Armée de Darius Roy de Perse, celui-ci lui demanda la Paix, & lui offrit la moitié de l’Asie, avec dix mille Talents. Parmenion, un de ses Favoris, charmé d’une Proposition si avantageuse, Seigneur, dit-il à son Maître, je vous proteste que si j’ètois Alexandre, j’accepterois ces offres avec joye; & moy aussi, lui répondit Alexandre, si j’ètois Parmenion.

10

The same Alexander being at Delphos, dragged the Priestess of Apollo to the Temple, in order to make her consult the Oracle upon a forbidden Day: She having resisted him in vain, cried out, Alexander thou art invincible. I desire no other Oracle but this, reply’d he.

Le même Alexandre, ètant à Delphes, entraina la Pretresse d’Apollon dans le Temple, pour lui faire consulter l’Oracle en un jour deffendu; Elle, s’écria, aprés lui avoir resisté en vain, Alexandre, tu ès invincible. Je ne veux point, dit-il, d’autre Oracle que celui-là.

11

Leo the Bizantine, a Disciple of Plato, and a very famous Philosopher, going to meet Philip King of Macedon, who came with a great Army against his Country, told him, Sir, why do you come to attack our City; because, said Philip, I am in Love with her, and am come to enjoy her. Ah! Sir, reply’d Leo, Lovers don’t come to their Mistresses with Instruments of War, but of Musick. This agreeable and witty Repartee so pleased Philip that he changed his Resolution, and leaving Byzantium at liberty, passed on to other Conquests.

Leon le Bizantin, Auditeur de Platon, & Philosophe fort fameux, ètant allé au devant de Philippe Roy de Macedoine qui venoit avec une grosse Armée attaquer sa Patrie, il lui dit, Seigneur, Pourquoy venez vous attaquer nôtre Ville? parce que j’en suis amoureux, dit Philippe, en raillant, & que je viens pour en jouir. Ah! Sire, reprit Leon, les Amans ne vont point chez leurs Maîtresses avec des instrumens de Guerre, mais avec des instrumens de Musique. Cette agréable & subtile réponse plût si sort à Philippe qu’il changea de resolution, & laissant Bizance en liberté, il passa à d’autres Conquetes.

12

One asked Pythagoras why he had married his Daughter to one of his Enemies; because, answered that Philosopher, I thought I could do him no greater injury than give him a Wife.

On demandoit a Pythagore, pourquoy il avoit marié sa Fille à un de ses Ennemis, ce Philosophe répondit, que c’estoit, parce qu’il croyait ne pouvoir lui faire un plus grand mal que de lui donner une Femme.

13

Diogenes seeing an ill Marks-man drawing his Bow, he put himself just before the Mark, and being asked why he did so, because, said he, he’ll be sure not hit me there.

Diogene voyant un Homme que tiroit de l’Arc, & qui en tiroit fort mal, se mit devant le but, on luy demanda, pourquoy il s’en mettoit si prés, c’est, répondit-il, afin qu’il ne me touche point.

14

Alexander going to see Diogenes the Cynick, He found him in a Field basking himself in the Sun; and accosting him, followed by all his Court, he said to him, I am Alexander the Great: And I, answered the Philosopher, am Diogenes the Cynick. Alexander made him several offers, and asked him what he desired of him; nothing, said Diogenes, but only that you stand a little aside, and don’t hinder the Sun to shine upon me. The King surprized with his Manners, cried out were I not Alexander, I could be Diogenes.

Alexandre allant voir Diogene le Cynique, il le trouva dans un champ expozé au Soleil, & l’abordant suivi de toute sa Cour, il luy dit, je suis le grand Alexandre; & moy, répondit le Philosophe, je suis Diogene le Cynique: Alexandre luy fit plusieurs offres, & luy demanda ce qu’il souhaitoit de lui? rien autre chose dit Diogene, si-non que tu te mettes un peu à côté, parce que tu empêches le Soleil de donner sur moy. Le Roy surpris de ces Manieres, s’êcria, si je n’ètois point Alexandre je voudrois être Diogene.

15

Pompey being Sick of a Feaver, one of his Friends came to see him, and as he came into his Room, he spied a handsom Woman Slave, whom Pompey loved, going out, he asked Pompey how it was with him, the Feaver, said Pompey, left me but just now: Very like, reply’d his Friend, for I met her a going from you.

Pompée ètant Malade de la Fievre, un de ses Amis le vint voir, & vit en entrant dans sa chambre une belle Escalve, dont Pompée ètoit amoureux, qui en sortoit: il demanda à Pompée comment il se portoit, la Fievre vient de me quitter, lui dit Pompée, je l’ai rencontrée qui sortoit de chez vous, lui dit son Ami.

16

The Emperour Augustus endeavouring to find the reason of the great likeness which a young Grecian bore to him, asked him whether his Mother was ever at Rome: No, Sir, answered the Grecian, but my Father has many a time.

L’Empereur Auguste cherchant des Raisons de la grande ressemblance qui ètoit entre lui & un jeune Homme Grec, lui demanda si sa Mere avoit jamais êté à Rome? Non, Seigneur, lui répondit le Grec, mais mon Pere y est venu plusieurs fois.

17

Pisistrates, a Tyrant of Athens, having resolved to marry a second Wife, his Children asked him whether he did it out of any discontent he had received from them. On the contrary, answered he, I am so well pleased with you, and find you to be such fine Men, that I have a mind to have other Children like you.

Pisistrate, Tyran d’Athenes, ayant resolu de se remarier, ses Enfans lui demanderent si c’ètoit à cause de quelque mécontentement qu’il eût receu d’eux. au contraire, leur répondit-il, je suis si content de vous, & je vous trouve si honnêtes Gens, que je veux avoir encore d’autres Enfans qui vous ressemblent.

18

Thales the Milesian, one of the Seven Wise-men of Greece, being asked what was the oldest Thing? He answered, God, because he has been for ever; what was the handsomest Thing? he said, the World; because it is the Work of God; what the largest Thing? Place; because it comprehends every thing besides; what the most convenient? Hope; because when all other Things are lost that remains still; what the best Thing? Virtue; for without it nothing that is Good can be said or done; what the quickest? a Mans Thoughts; because in one Moment they run over all the Universe; what the strongest? Necessity; because it surmounts all other Accidents; what the easiest? to give Councel; what the hardest? to know ones self; what the wisest Thing? Time; because it brings all Things to pass.

Thales Milesien, l’un des sept Sages de Grece, étant interrogé quelle étoit la chose la plus ancienne? répondit que c’étoit Dieu; parce qu’il a toûjours été; quelle étoit la chose la plus belle? il dit que c’étoit le Monde; parce que c’est l’ouvrage de Dieu? quelle étoit la chose la plus grande? le lieu; parce qu’il comprend toute autre chose; quelle chose étoit la plus Commode? l’Esperance; parce qu’aprés avoir perdu tous les autres biens, elle reste toûjours; quelle chose ètoit la Meilleure? la vertu; parce que sans elle, on ne peut rien dire, n’y rien faire de bon; quelle chose ètoit la plus promte? l’esprit de l’homme; parce qu’en un moment il parcourt tout l’Univers; quelle chose ètoit la plus forte? la Necessité; parce qu’elle surmonte tous les autres Accidens; quelle chose ètoit la plus facile? de donner conseil; quelle chose ètoit la plus difficile? de se connoître soy même; quelle chose ètoit la plus Sage? le temps, répondit-il, parce qu’il vient à bout de tout.

19

A certain Soldier came in a great Fright to Leonidas and told him, Captain, the Enemy are very near us; then we are very near them too, said Leonidas. There was another that came to tell him that the Enemy were so numerous that one could hardly see the Sun for the quantity of their Arrows; to whom he answered very pleasantly, will it not be a great Pleasure to fight in the shade?

Vn certain Soldat fort épouvanté, se presenta devant Leonidas, & luy dit, mon Capitaine les Ennemis sont fort prez de nous; & bien, nous sommes donc aussi fort prés d’eux, répondit Leonidas. Il y en eut un autre qui luy rapporta que le nombre des Ennemis ètoit si grand, qu’à grand peine pouvoit on voir le Soleil par la quantité de leurs dards; il luy répondit fort agréablement, ne sera-ce pas un grand plaisir de combatre à l’ombre?

20

Alexander the Great asked Dionides, a famous Pirate, who was brought Prisoner to him, why he was so bold as to rob and plunder in his Seas, he answered, that he did it for his Profit, and as Alexander himself was used to do; but because I do it, added he, with one single Gally, I am called a Pirate: But you Sir, Who do it with a great Army are called a King. That bold Answer so pleased Alexander that he gave him his Liberty, at that very instant.

Alexandre le grand demandoit â Dionides fameux Corsaire qui luy avoit été amené prisonnier, pour quelle raison il avoir été si hardy que de pirater & de faire des courses sur ses Mers; il répondit, que c’ètoit pour son profit, & comme Alexandre avoit coûtume de faire lui même, mais parce que je le fais, ajouta-til, avec une seule Galere, l’on m’appelle Corsaire; mais vous, Seigneur, qui le faites avec une grande Armée, l’on vous appelle Roy. Cette réponse hardie plût tant à Alexandre, qu’il lui donna aussi tôt la liberté.

21

Darius King of Persia sent great Presents to Epaminondas, General of the Thebans, with design to tamper with him: If Darius, said this great Captain to those that brought those Presents to him, has a mind to be Friends with the Thebans, he need not buy my Friendship; and if he has other Thoughts, he has not Riches enough to corrupt me; and so he sent them back.

Darius Roy de Perse, envoya de grands Presents à Epaminondas, Chef des Thebains, pour tâcher de le corrompre: Si Darius veut être Ami des Thebains, dit ce grand Capitaine à ceux qui les lui portoient, il n’est pas nécessaire qu’il achete mon amitié; & s’il a d’autres sentiments, il n’est pas assez riche pour me corrompre. Et ainsi il les renvoya.

22

Corax promised Tisias to teach him Rhetorick, and Tisias on his side engaged to give him a Reward for it; but when he had learnt it, he refused to satisfy him: Corax therefore called him before the Judge; Tisias trusting to the subtilty of his Rhetorick, asked him what Rhetorick consisted in: Corax answered in the Art of Perswading. Then said Tisias, If I can perswade the Judge that I ought to give you nothing, I’ll pay you nothing, because you will be cast; and if I do not perswade them, I shan’t pay you neither; because I have not learnt how to perswade; therefore your best way is to relinquish your enterprize. But Corax, who was more subtle than he, resumed the Argument in this Manner, if you perswade the Judges you ought to pay me; because you have learnt Rhetorick; if you do not perswade them, you must pay me likewise, because you will be cast; so let it be how it will you ought to satisfy me.

Corax promit à Tisias de luy enseigner la Rhétorique, & Tisias de son côté s’engagea de lui en payer le Salaire; mais l’ayant apprise, il ne vouloit point le satisfaire, c’est pourquoy Corax l’appella en justice. Tisias se fiant sur la subtilité de sa Rhétorique lui demanda, en quoy consistoit la Rhétorique: Corax repondit, qu’elle consistoit dans l’art de persuader. donc dit Tisias, si je persuade les juges, que je ne te dois rien donner, je ne te payeray aucune chose, parce que je gagneray le procez; & si je ne les persuade pas, je ne te payeray pas non plus, parce que je n’auray pas appris à persuader; ainsi tu feras mieux d’abandonner l’entreprise. Mais Corax qui ètoit plus fin que luy, reprit l’argument de cette maniere; si tu persuades les juges, tu me dois payer, parce que tu auras appris la Rhétorique, si tu ne les persuader pas, tu me dois payer de même; parce que tu perdras ton procez, ainsi de quelle façon que ce soit tu dois me satisfaire.

23

Mecenas, Augustus’s Favourite, being entertained at Dinner by a Roman Knight, towards the end of the Meal, began to take some Liberties with his Wife; the Knight, to make his court to him, instead of shewing any jealousy of it, counterfeited Sleep; but seeing one of his Slaves going to take away something from the Cup board, Sirrah, says he, doest thou not see that I only sleep for Mecenas?

Mécéne Favori d’Auguste, étant regalé par un Chevalier Romain, sur la fin du repas il commença à prendre quelque libertez avec sa Femme. le Chevalier pour lui faire sa Cour, au lieu d’en paroitre jaloux, fit semblant de dormir; mais voyant qu’un de ses Esclaves alloit emporter quelque chose du Buffet, Coquin, lui dit-il, ne vois tu pas que je ne dors que pour Mécéne?

24

There was at Rome, in the Time of the Emperour Augustus, a poor Greek Poet who from time to time, when the Emperour went out of his Palace, presented him with a Greek Epigram; and though the Emperour took it, yet he never gave him any thing; on the contrary, having a mind one Day to ridicule him and shake him off, assoon as he saw him coming to present him with his Verses, the Emperour sent him a Greek Epigram of his own Composing, and writ with his own Hand. The Poet received it with joy, and as he was reading of it, he shewed by his Face and Gestures that he was mightily pleased with it. After he had read it, he pulled out his Purse, and coming up to Augustus, gave him some few Pence, saying, take this Money, Cesar, I give it you, not according to your great Fortune, but according to my poor Ability; had I more, my liberality would be greater. The whole company fell a laughing, and the Emperour more than the rest, who ordered him a hundred thousand Crowns.

Il y avoit à Rome, du tems de l’Empereur Auguste, un pauvre Poëte Grec qui de temps en temps, lors que l’Empereur sortoit du Palais, lui presentoit une épigramme Grecque, mais quoy que l’Empereur la prit, il ne luy donnoit pourtant jamais rien; au contraire, voulant un jour se moquer de lui, & le congedier, lors qu’il le vit venir pour presenter ses Vers, l’Empereur lui envoya une épigramme en Grec de sa composition, & écrite de sa main; le Poëte la receut avec joye, la leut, & fit voir en la lisant par son Visage & par les gestes qu’elle lui plaisoit beaucoup: l’ayant leüe, il tira sa bourse, & s’approchant d’Auguste, il lui donna quelques Sols, lui disant, prenez cét argent Cesar, je vous le donne, non selon vôtre haute fortune, mais selon mon petit pouvoir, si j’en avois davantage ma liberalité seroit plus grande; tout le monde se mit à rire, l’Empereur lui même plus que les autres, & lui fit donner cent mille écus.

25

Young Scipio was at four and twenty Years of Age a Man of consummate Wisdom; and altho his warlike Atchievements terrified his Enemies, yet he made still greater Conquests by his Virtue than by his Valour. For as they brought to him the Wife of Mando a Spanish Prince, with two of her Nieces extream Beautiful, he sent them back with these fine Words, That it not only became his own, and the Roman Peoples integrity not to violate any thing that’s Sacred; but besides the regard he had for them, obliged him to do them Justice; since in their Misfortune they had neither forgot themselves, nor their Honour. And having done the same to another Spanish Prince, whose Wife, (a Woman still more accomplisht in her Beauty than the other) had been presented to him, he sent her back to her Husband with a great Sum of Money which was offered him for her Ransom. This Prince highly pleased with this Favour, proclaimed through all the Land, That a God-like young Roman was come into Spain, who made himself Master of all not so much by the Power of his Arms, as of his Virtue and obliging Nature.

Le jeune Scipion à l’âge de vingt quatre ans ètoit déja d’une Sagesse consommée: & quoy qu’il fit des Exploits d’Armes qui ètonnoient ses Ennemis, il fit encore de plus grandes Conquêtes par sa Vertu, que par sa Valeur. Car lors qu’on lui eût amené la Femme de Mandon, Prince Espagnol, & deux des ses Nieces d’une excellente Beauté, il les renvoya avec ces belles Paroles: Qu’outre qu’il ètoit de son integrité, & de celle du Peuple Romain de ne rien violer de saint, leur propre consideration l’obligeoit encore à leur faire justice: puis que dans leur malheur, elles ne s’ètoient pas oubliées d’elles, ni de leur Vertu. Et ayant fait la même chose à un autre Prince Espagnol, dont on lui avoit presentê la Femme, d’une Beauté encore plus accomplie que l’autre, il la renvoya à son mary avec une grande somme d’Argent qu’on lui offroit pour sa rançon. Ce Prince charmé de cette Grace publia dans le Païs, qu’il ètoit venu en Espagne un jeune Romain semblable aux Dieux, qui se rendoit Maître de tout, moins par la force de ses Armes que par celle de sa Vertu & de son humeur bienfaisante.

26

The same Scipio being accused before the Roman People, by Q. Petilius, for embezling part of the Spoils of King Antiochus, he made his appearance at the Day appointed by his Accuser. But this great Man no less admirable by his Virtue than by his Courage, instead of clearing himself from the Charge, and proud of his own Innocence, he made a Speech to the People assembled to condemn him, and told them with a bold and undaunted Look, and the Tone of a Conquerour, ’Twas upon such a day as this is I took Carthage, defeated Hannibal, and vanquished the Carthaginians; let’s march to the Capitol, and return the Gods Thanks for it. The People surprised by this Magnanimity left the Informer, followed Scipio, and that Day got him a thousand times more Honour than that on which he triumphed over King Siphax, and the Carthaginians.

Le même Scipion ètant accusé devant le Peuple Romain par Q. Petilius, d’avoir distrait une partie des depouilles du Roy Antiochus à son profit, parut au jour marqué par son Accusateur. Mais ce grand Homme, admirable par sa vertu & par sa valeur, au lieu de se justifier de ce qu’on l’accusoit, fier qu’il ètoit de son innocence, parlant au Peuple assemblé pour le condamner, dit d’un air hardi & intrepide, & d’un ton de vainqueur. C’est à tel jour qu’aujourd’huy, que j’ay pris Carthage, que j’ay défait Hannibal, & vaincu les Carthaginois, allons au Capitole en remercier les Dieux. Le Peuple surpris de cette Magnanimité, quitta l’accusateur, suivit Scipion, & ce jour lui fut mille fois plus glorieux, que celui auquel il triompha du Roy Siphax, & des Carthaginois.

27

Plato invited one Day to Supper Diogenes the Cynick with some Sicilians his Friends, and caused the Banqueting Room to be adorned, out of respect to those Strangers. Diogenes who was displeased with the finery of Plato, began to trample upon the Carpets and other Goods, and said very brutishly, I trample upon the Pride of Plato: But Plato answered wisely, True, Diogenes, but you trample upon it through a greater Pride.

Platon invita un jour à souper Diogene le Cynique avec quelques Siciliens de ses Amis, & fit orner la sale du Banquet pour faire honneur à ces Etrangers. Diogene qui ne pouvoit souffrir la propreté de Platon, commenta à fouler aux Pieds les Tapis & les autres meubles, & dit fort brutalement: je foule aux Pieds l’orgueil de Platon: & Platon lui répondit sagement, il est vray, Diogene, mais vous le foulez par un plus grand orgueil.

28

Cineas was in great Honour with Pyrrhus King of Epirus, who made use of him in all his weighty Affairs, and profest that he had won more Cities by the Charms of his Eloquence, than he had taken himself by the strength of his own Arms. He perceiving the King earnestly bent upon his Expedition into Italy, told him in private, Sir, the Romans have the Reputation of a Warlike People, and command divers Nations that are so, but suppose we overcome them, What Fruit shall we reap by the Victory? That’s a plain thing, said Pyrrhus; for then added he, No City will presume to oppose us, and we shall speedily be Masters of all Italy. And having made Italy our own, return’d Cineas, what shall we then do? Sicily, said he, is near, reaching out her Hand to us, a rich and populous Island, and easily to be taken. It is probable, said Cineas; but having subdued Sicily, will that put an end to the War? If God, said Pyrrhus gives us this success, these will be but the Flourish to greater Matters; for who can refrain from Africa and Carthage, which will be soon at our beck? And these overcome, you will easily grant that none of those that now provoke us, will dare to resist us: That’s true, said Cineas; for ’its easiy to believe that with such Forces we may recover Macedon, and give Law to all Greece. But being thus become Lords of all, what then? Then dear Cineas, said Pyrrhus smiling, we will live at our ease, and enjoy our selves. When Cineas had brought him thus far; and what hinders, replied he, but that we may now do all this, seeing it is in our Power, without the expence of so much sweat and Blood?

Cineas ètoit en grande estime auprès de Phyrrus Roy d’Epire qui se servoit de lui dans toutes ses Affaires importantes, & avoüoit qu’il avoit gagné plus de Villes par les charmes de son Eloquence, qu’il n’en avoit pris lui même par la force de ses Armes. Comme il vit que le Roy avoit tourne toutes ses Pensées vers l’expedition d’Italie, il lui dit un jour en particulier: Sire, les Romains passant pour un Peuple Guerrier, & commandent à plusieurs Nations qui le sont aussi, mais supposé, que nous les vainquions, quel fruit retirerons nous de cette Victoire? La chose parle d’elle même, dit Phyrrus, car alors, ajoûta-t-il, aucune Ville n’osera nous resister & nous serons bien-tôt Maîtres de toute l’Italie. Et quand nous aurons l’Italie, repliqua Cineas, que ferons nous alors? La Sicile, dit-il, est prés & nous tend les Bras: Isle riche & peuplée qui sera facilement reduite: il y a quelque apparence, dit Cineas; mais aprés avoir subjugué la Sicile, cela mettra t-il fin à la Guerre? Si Dieu, dit Phyrrus, nous donne ce bon succez, ce ne seront que les Preludes de plus grandes choses; car comment s’empêcher de passer en Afrique & d’aller à Carthage, qui sera bien tôt à nôtre commandement? Et étant venus à bout de tout ceci vous m’avoüerez aisement qu’aucun de ceux qui nous bravent maintenant, n’osera nous resister. Cela est vray, dit Cineas; car il est assez croyable qu’avec de telles Forces nous pourrons recouvrer la Macedoine, & faire la loy à toute la Grece. Mais aprés nous être ainsi rendus Maîtres de tout, que ferons nous alors? Alors, cher Cineas, lui dit Phyrrus, d’un air gay, nous vivrons à nôtre aise, & nous nous donnerons du bon tems. Cineas l’ayant fait venir là, & à quoi tient-il, repliqua-t-il, que nous ne le fassions dés à present puis que cela depend de nous sans tant de sang & de peine?

29

Chilo said, one ought to be young in his old Age, and old in his youth; that is, an old Man ought to be Chearful and Good-humour’d, and a young Man Wise.

Chilon disoit, il faut être jeune en sa vieillesse, & vieux en sa jeunesse; c’est-à dire qu’un vieillard doit être sans chagrin, & qu’un jeune homme doit être sage.

30

Artaxerxes being routed in a Battle, and put to flight, after his Baggage and Provisions had been plundered, he found himself so prest with Hunger, that he was reduced to eat a piece of Barly Bread, and some dry Figs. He relished them so well, that he cried out. O Gods! how many Pleasures has Plenty deprived me of till this instant?

Artaxerces, dans un combat, ayant été obligé de prendre la fuite aprés que son bagage & ses Provisions eurent été pillées, il se trouva si fort pressé de la faim qu’il fut reduit à manger un morceau de pain d’orge & quelques figues seches. Elles lui parurent de si bon goût qu’il s’écria: O Dieux! de combien de plaisirs l’abondance m’a-t-elle privé jusqu’ à ce moment.

31

Those of Cyrene desired Plato to make Laws for them, I cannot, said he, dictate Laws to those whom Plenty and Prosperity has made incapable to obey.

Ceux de Cyrene priérent Platon de leur dresser des Loix; je ne puis, leur dit-il, prescrire des Loix à ceux que l’abondance & la prosperité rendent incapables d’obeir.

32

Archidamus besieging Corinth, saw a great many Hares starting from under its Walls: Then turning presently to his Soldiers, These my Friends, said he, are the Enemies we are to fight withal, we ought to be more afraid of their Heels than of their Hands.

Archidamus, assiegeant Corinthe, vit sortir plusieurs Liévres de dessous ses murs: aussi-tôt se tournant vers ses Soldats: Voilà, dit-il, Compagnons, les Ennemis que nous avons à combattre, nous devons plus craindre leurs pieds que leurs bras.

33

Julius Cesar landing on the Shore of Africa, happened to get a fall as he went out of the Ship. This fall which seemed to be an ill Omen for his Design upon that Country, was by his ready Wit turned into a lucky Presage; for as he fell he embraced the Earth, and cried, Now I hold thee Africa.

Jules Cesar qui abordoit au rivage d’Affrique tomba en descendant du vaisseau: cette chûte qui sembloit de mauvais augure pour les desseins qu’il avoit sur ce Païs, fut par son adresse changée en un présage heureux; il embrassa la Terre en tombant, & il s’écria; c’est à present, Afrique, que je te tiens.

34

Timotheus being accounted lucky in his Undertakings, was by some envious Persons drawn with a Net in his Hand, into which Cities fell of their own accord while he was asleep. Timotheus without expressing the least discontent upon it, said to those who shewed him that Picture, If I take such fine Cities while I am asleep, what shall I do when I am awake?

Timotheus, qui ètoit estimé heureux dans ses entreprises, fut par quelques envieux representé avec des filets en main, où les Villes venoient se jetter pendant qu’il dormoit; Timotheus, sans en temoigner le moindre chagrin, dit à ceux qui lui montroient cette Peinture: Si je prens de si belles Villes en dormant, que ferai je quand je serai èveillé?

35

Sylla who robbed the Temples to pay his Soldiers, was told that as they were going to plunder that of Apollo at Delphos, a noise of some Instruments was heard there; so much the better, answered he, for since Apollo plays on his Lyre, ’tis a sign he is pleased, and is not angry with us.

Sylla qui dépoüilloit les Temples pour payer ses Soldats, fut averti que comme on alloit piller celui d’Apollon à Delphes, on y avoit oüy le son de quelques Instrumens, Tant mieux, répondit-il, puisqu’ Apollon jouë de sa Lyre, c’est une marque qu’il est de belle humeur, & qu’il n’est point irrité contre nous.

36

Alexander’s Generals complained to him just before the Battle of Arbella, that his Soldiers had been so insolent, as to demand a Promise that the whole Booty should be theirs: Come on, said he, that’s a sign of Victory; those that speak with so much assurance do not design to run away.

Les Capitaines d’Alexandre se plaignirent à la journée d’Arbelles, que ses Soldats avoient l’insolence de vouloir qu’on leur promît tout le butin: Courage, leur dit-il, c’est un presage de la victoire: quand on parle avec cette asseurance là, on n’a pas envie de fuir.

37

Diogenes came to Cheronea when Philip his Army was there; he was taken by the Soldiers and carried before the King, who not knowing him, told him that without doubt he was a Spy, and came to observe him. Thou sayest right, answered Diogenes, for I came hither to observe thy Folly, in that not being contented with the Kingdom of Macedon, thou seekest at the hazard of thy Dominions, to Usurpe the Province of thy Neighbours. The King admiring the boldness of this Man, commanded him to be set at Liberty.

Diogene vint à Cheronée lorsque l’armée de Philippe y étoit; il fut pris par ses Soldats, & conduit au Roi qui ne le connoissant pas, lui dit que sans doute il étoit un Espion, qui venoit pour l’observer: Tu as raison, repondit Diogene, car je suis venu en ce lieu pour observer ta folie, qui fait que non content du Royaume de Macedoine, tu cherches, au peril de ta vie, & de tes Etats, à usurper les Provinces de tes voisins. Le Roy admirant la hardiesse de cét homme commanda qu’on le mît en liberté.

38

Julius Cesar going through a little Village, some of his Friends took notice of the Tranquility of the Inhabitants, and asked him whether he thought there was any great canvassing and interest made for the Magistracy: I had rather, answered Cesar, be the first Man in this Village, than the second at Rome.

Jules Cesar passant dans un petit bourg, quelques uns de ses amis qui remarquoient la tranquilité des habitans, lui demanderent, s’il croyoit qu’il y eût là de grandes brigues pour le gouvernement: J’aimerois mieux, répondit Cesar, être le premier dans ce village, que d’étre le second à Rome.

39

Darius’s Mother, then Prisoner of Alexander, excusing her self to him, for that in one visit wherewith he honoured her, she by a mistake, had paid to Ephestion, who accompained him, the Respect due to the King: said Alexander comforting her, be not concerned at it, Madam, you were not mistaken, for he whom you saluted is another Alexander.

La Mere de Darius prisonniere d’Alexandre, lui faisant ses excuses de ce qu’en une visite dont il l’honora, elle avoit par meprise rendu à Ephestion, qui l’accompagnoit, les respects dûs à ce Roy: Alexandre, lui dit en la rasseurant, ne vous troublez point, Madame, vous ne vous êtes pas trompée celui que vous avez salué est un autre Alexandre.

40

Chilo, one of the seven wise Men of Grece, to give us to understand, that one ought to be moderate and cautious in ones Affections, said, We must love a Friend so as we may one Day hate him; and we must hate no Body but with a regard that we may afterwards unite Friendship with him.

Chilon un des sept Sages de la Grece, pour nous faire entendre qu’il falloit être moderé & prudent dans ses affections, disoit: Il faut aimer un ami comme le pouvant haïr quelque jour, & il ne faut haïr personne, qu’en vüe qu’on peut ensuite noüer amitié avec lui.

41

One comforting King Philip upon the Death of Hipparchus, told him, that his Friend being stricken in Years, Death was not come upon him before his time; True, said Philip, Death is come in time for him; but since I had not yet honoured him with Benefits worthy of our Friendship, his Death, as to me, is untimely.

Quelqu’un consolant le Roi Philippe de la mort d’Hypparchus, lui disoit que cét ami étant déjà fort âgé, la mort ne l’avoit point attaqué avant le temps. Il est vray, répondit Philippe, que la mort est venuë à temps pour lui, mais puisque je ne l’avois pas encore honnoré des Biens faits dignes de nôtre amitié, sa mort, à mon ègard, est premature.

42

A Criminal sentenced to Death, was bailed out of Prison by one of his Friends, who remained Prisoner till the other had settled some Business, which assoon as he had done he surrendred himself again; Dionysius the Tyrant surprized at the Assurance of the one, and the Faithfulness of the other, pardoned the Malefactor: And in requital of my Pardon, said he, I beseech you to admit me as a third into your Friendship.

Un Criminel condamné à la Mort, sur le cautionnement d’un de ses Amis qui demeura en sa place sortit de Prison pour aller regler quelques Affaires, & revint aussi-tôt qu’il les eût achevées: Denis le Tyran surpris de l’asseurance de l’un, & de la fidelité de l’autre, pardonna au Criminel: En reconnoissance, dit-il, de ma grace, je vous conjure de me recevoir pour troisiéme en vôtre amitié.

43

Memnon King Darius’s General, in his War against Alexander, hearing one of his Soldiers belch out many injurious Words against that great Enemy, he gave him a great blow with a Halbert, and told him, I pay thee to fight against Alexander, and not to abuse him.

Memnon Capitaine de Darius, dans la Guerre qu’il avoit contre Alexandre, entendant un de ses Soldats vomir insolemment beaucoup d’injures contre ce grand Ennemi, il lui donna un grand coup de Hallebarde; en lui disant, je te paye afin que tu combattes contre Alexandre, non pas afin que tu l’injuries.

44

The Physician of Pyrrhus having offered to Fabricius, the Roman General, to Poison his Master, Fabricius sent back that Traitor’s Letter to Pyrrhus, with these Words, Prince, know better for the future, how to choose both your Friends and Foes. To requite this Benefit, Pyrrhus sent back all the Prisoners: But Fabricius received them only upon Condition that he would accept of as many of his, and writ to him: Do not believe Pyrrhus, I have discovered this Treachery to you, out of a particular regard to your Person, but because the Romans shun base Stratagems, and will not triumph but with open Force.

Le Medecin de Phyrrus s’ètant offert à Fabricius general des Romains, d’empoisonner son Maître, Fabricius renvoya la lettre de ce Traitre à Phyrrus avec ces Mots; Prince, songez à l’avenir à faire un meilleur choix de vos Amis, & de vos Ennemis. En reconnoissance de ce bienfait, Phyrrus lui renvoya tous les Prisonniers: Mais Fabricius ne les reçût qu’à la charge de lui en rendre autant des siens, & lui manda: Ne crois pas, Phyrrus, que je t’aye decouvert cette Trahison, par une consideration particuliere de ta Personne, mais parce que les Romains fuyent les lâches Artifices, & ne veulent triompher qu’à force ouverte.

45

Diogenes being asked of what Beast the biting was most dangerous, answered, if you mean wild Beasts, ’tis the Slanderer’s, if tame one’s, the Flatterer’s.

Diogene interrogé quelle Bête mordoit le plus dangereusement, répondit: Si vous parlez des Bêtes farouches, c’est le medisant; si des animaux domestiques, c’est le flateur.

46

Antigonus hearing a Poet call him Son of Jupiter; My Valet de Chamber, said he smiling, who empties my Close-stool, knows but too well that I am but a Man.

Antigonus entendant un Poëte flateur l’appeller Fils de Jupiter: Mon Valet de chambre, dit-il en soûriant, qui vuide ma chaise percée sçait trop bien que je ne suis qu’un Homme.

47

Whereas Kings are surrounded with Flatterers, and that Horses have no particular regard for them, Carneades used to say, That Princes learn nothing well, but to ride on Horseback.

Comme les Rois sont environnez de Flateurs, & que les seuls Chevaux ne gardent point avec eux de mesures, Carneades disoit: que les Princes n’apprennent rien comme il faut qu’à bien manier un Cheval.

48

Sesostris King of Ægypt, having caused four of his Captive Kings, instead of Horses, to draw his Triumphal Chariot, one of these four cast his Eyes contiually upon the two foremost Wheels next him, which Sesostris observing, ask’d him what he found worthy of his Admiration in that Motion; to whom the Captive King answer’d, That in those Wheels he beheld the mutability of all worldly Things; for that the lowest part of the Wheel was suddenly carried above and became the highest, and the uppermost part was as suddenly turned downwards; which when Sesostris had judiciosly weighed, he dismist those Kings from their Servitude.

Sesostris Roy d’Egypte, ayant fait tirer son char de Triomphe par quatre Rois Captifs, au lieu de Chevaux, un d’eux tenoit la veuë attachée sur les Roües de devant qui ètoient prés de lui, ce que Sesostris remarquant, il lui demanda ce qu’il trouvoit digne d’admiration dans ce mouvement. A quoi le Roy Captif répondit: je contemple dans ces Roües l’inconstance des choses humaines, d’autant que la partie la plus basse de la rouë est tout d’un coup portée en haut, & devient la plus élevée; & la plus haute est portée en bas avec autant de vitesse; Sesostris ayant meurement reflechi là dessus, mit ces Rois en liberté.

49

Some Body twitting Hiero the Tyrant with a stinking Breath, he chid his Wife for not telling him of it before: I thought, answered she, all Mens Breaths smelled like yours.

On reprocha au Tiran Hieron qu’il avoit l’haleine puante, il reprit sa Femme de ne l’en avoir jamais averti; Je croyois, répondit-elle, que tous les Hommes eussent l’haleine de même odeur que vous.

50

One asked Charillus, why at Lacedemon Maids went bare-faced, when Married Women were vailed: Because, answered he, the first look for Husbands, and the others are afraid to lose them by Jealousie and Divorce,

On demandoit à Charillus pourquoi à Lacedemone les Filles marchoient le visage decouvert, veu que les Femmes ètoient voilées, c’est répondit il: parce que les unes cherchent un mari, & que les autres ont peur de le perdre par la jalousie & par le divorce.

51

Diogenes seeing over the Door of a new Married Man, these written Words, Hence all Evil; said he, After Death the Physician. The same Philosopher perceiving one Day some Women hanged on an Olive-tree: Would to God, cried he, all other Trees bore the like Fruit.

Diogene voyant sur la porte d’un nouveau marié ces Mots écrits, loin d’ici le Mal, il dit, Aprés la Mort le Medecin. Le même Philosophe apperceût un jour des Femmes penduës à un Olivier: Plût à Dieu, s’écria-t-il, que tous les autres Arbres portassent un semblable fruit!

52

Paulus Æmilius divorced a Wife, who seemed to be Mistress of all the Qualifications necessary to make her beloved. This Divorcement surprized a great many; but he told them, shewing them his Shoe, You see that this Shoe fits me, and is well made, but you don’t see where it wrings me.

Paulus Æmilius repudia une Femme qui paroissoit avoir tous les avantages capables de se faire aimer. Ce divorce ètonnoit bien des Gens, mais il leur dit en montrant son Soulier: Vous voyez que ce Soulier est propre, qu’il est bien fait: mais vous ne voyez pas où il blesse.

53

Diogenes said to a young hare-brained Fellow, that threw Stones at a Gibbet; Well, I see thou’lt touch the mark at last.

Diogene dit à un jeune étourdi qui jettoit des Pierres vers un Gibet: Courage, je vois bien qu’enfin tu toucheras au but.

54

C. Popilius, who, as Ignorant as he was, set up for a Lawyer, being one Day summoned to be a Witness, answered he knew nothing: You think, perhaps, said Cicero to him, that you are asked Questions about Law.

C. Popilius qui tout ignorant qu’il ètoit s’érigeoit en Jurisconsulte, ètant un jour appellé en témoignage, répondit qu’il ne savoit rien: Vous pensez peut être, lui dit Ciceron, qu’on vous Interroge sur des questions de Droit?

55

Melanthus, a Parasite of Alexander King of Pheres, being asked how his Master died, made this pleasant Answer: he died by a Sword that run through his Thigh, and my Belly at once.

Melanthus Parasite d’Alexandre, Roy de Pheres, interrogé comment son Maître ètoit Mort, répondit plaisamment: Il est mort d’un coup d’Epée qui lui perça la cuisse & mon ventre en même tems.

56

Plato, said, that Hopes are the Dreams of those that are awake.

Platon disoit, que les Esperances sont les songes des Personnes éveillées.

57

As two Men courted Themistocles’s Daughter in Marriage, one of which was a Fool, but rich, the other Poor, but wise and honest; he chose this last for his Son-in-law, and answered to those who wondred at it: I esteem more a Man without Riches, than Riches without a Man.

De deux hommes qui recherchoient la Fille de Themistocles, l’un sot, mais riche: l’autre pauvre, mais sage & honnête homme, il prit ce dernier pour son gendre, & répondit à ceux qui s’en ètonnoient: J’aime mieux un Homme sans richesses, que des richesses sans Homme.

58

Alexander the Great, took in the Wars a certain Indian, who had such a skill in Shooting, that he could pass his Arrows through a Ring placed at a certain distance. He commanded him to make a trial of it before him; and because the Indian refused, he ordered he should be slain. Those that led him to his Punishment enquiring into the Reason of his refusal, the Indian answered, Having for a long time left off the Exercise of my Art, I chuse to suffer Death rather than to venture the loss of my Reputation, if I should miss before Alexander: Which being told again to that Emperour, he not only commanded he should be set at Liberty, but also gave him many Gifts, admiring his great Spirit and Resolution.

Alexandre le grand prit en Guerre un Indien, si adroit à tirer de l’Arc, qu’il faisoit passer ses Flêches par un anneau placé à une certaine distance, il lui commanda d’en faire l’essai devant lui, & sur le refus qu’en fit l’Indien, il ordonna qu’on le fit mourir. Ceux qui le conduisoient au supplice, s’informant du sujet de son refus, l’Indien repondit: Comme j’ai été long tems sans exercer mon art, j’ai mieux aimé souffrir la Mort, que de m’exposer à perdre ma Reputation, en manquant devant Alexandre. Ce qui ètant rapporté à cet Empereur, non seulement il le fit mettre en liberté, mais même il lui fit de grands Presents, admirant son courage & sa fermeté.

59

The Favourites of the Emperour Trajan, taking notice that he received every Body with great Familiarity, told him he forgot the grandeur of his Majesty: I will take care, answered he, That my People shall find in me such an Emperour as I could wish to have one my self, if I was a private Man.

Les Favoris de l’Empereur Trajan le voyant recevoir tout le monde fort familierement, lui remontroient qu’il oublioit la grandeur de sa Majesté: je veux, répondit-il, que mon Peuple trouve en moy un Empereur, tel que je souhaiterois en avoir un si j’étois Homme privé.

60

Agathocles from a mean Fortune, being advanced to the Royal Dignity, would be served at Table with Earthen-ware, and being asked the reason: I intend, answered he, that the remembrance of my Extraction from a Potter, shall check that Pride which the vain Pomp of Royalty may raise in me.

Agathocles ètant parvenu de bas lieu â la dignité Royalle, vouloit qu’on le servit à Table en Vaisselle de Terre, & quand on lui en demandoit la cause: je veux, répondit-il, que le souvenir de l’Origine que je tire d’un Potier de Terre, rabatte l’orgueil, dont le vain appareil de la Royauté pourroit me surprendre.

61

Alexander sitting on the Judgment Seat to decide Criminal Causes, kept always one of his Ears stopt, while the Accuser was pleading; and being asked the reason: I keep, said he, the other Ear entire to hear the Party accused.

Alexandre ètant assis sur le Tribunal pour juger les Causes criminelles, tenoit toûjours une Oreille bouchée pendant que l’Accusateur plaidoit, & comme on lui en demandoit la raison, je reserve, dit-il, l’autre Oreille entiere pour entendre l’Accusé.

62

King Philip being drowsy, and not having well heard the Cause of Machetes, cast him contrary to the Laws: Machetes cryed out presently that he appealed; the King in a Passion asked him to what Judge? I appeal, said he, from Philip asleep, to Philip awake. This reply made Philip recollect himself, and ordered the Cause to be tried over again, who acknowledging his Errour, he did not revoke his Sentence, but paid out of his own Pocket the Sum which he had adjudged Machetes to pay.

Le Roy Philippe assoupi, ayant mal entendu la cause de Machetes, il le condamna contre les Loix; Machetes s’écria aussi-tôt qu’il en appelloit. Le Roy en colere lui demanda à quel Juge? j’en appelle, répondit-il, de Philippe endormi, à Philippe éveillé. Ce Mot fit rentrer Philippe en lui même; il fit derechef plaider la cause, & voyant en effet son erreur, il ne cassa pas à la verité son arrest, mais il paya lui même de ses deniers la somme à laquelle il avoit condamné Machetes.

63

Two Criminals accused one another before the same King: This Prince having patiently heard them both, said, I condemn this Fellow presently to depart my Kingdom, and the other to run after him.

Deux Criminels s’accusoient l’un l’autre devant ce même Roy: Ce Prince aprés les avoir écoutez patiemment, dit: je condamne celui ci à sortir promptement de mon Royaume, & l’autre à courir aprés.

64

In the Tryal of a Cause, whereof Aristides was Judge, one of the Parties related several Abuses which the same Aristides had received from his adverse Party: Let that pass, said Aristides, I am not here to be my own Judge, but yours only.

Dans une cause où Aristide ètoit juge, une des Parties rapporta plusieurs injures que ce même Aristide avoit receu de sa partie adverse: Passez cela, dit Aristide, venez au fait: je ne suis pas ici mon juge, je ne suis que le vôtre.

65

Marcus Aurelius said to some Persons who would keep his Son from weeping for his Tutors death; Suffer my Son to be a Man before he be an Emperour.

Marc Aurele dit à quelques Personnes qui vouloient empêcher son Fils de pleurer la Mort de son Precepteur: Souffrez que mon Fils soit Homme, avant que d’être Empereur.

66

Dionysius seeing that his Son had gathered a great quantity of Gold and Silver Vessels, out of the Gifts he had made him, told him: I do not find in thee a Royal Soul, since thou hast neglected to get thy self Friends by the distribution of those Riches.

Denys voyant que son Fils avoit amassé une grande quantité de Vases d’Or & d’Argent des dons qu’il lui avoit fait, il lui dit, je ne connois point en toi une Ame Royale, puis que tu as negligé de te faire des amis par la distribution de ces Richesses.

67

The same Dionysius asked Diogenes what Brass he should take to make himself a Statue: Take that, answered he, of the Statues of Harmodius and Aristogiton. These were two famous Murderers of Tyrants, to whom Statues had been erected.

Le même Denys demanda à Diogene quel Cuivre il prendroit pour se faire une Statuë: Prenez, lui répondit-il, celui des Statuës d’Harmodius & d’Aristogiton. C’ètoient deux fameux tueurs de Tyrans à qui on avoit dressé des Statues.

68

An old Soldier having a Sute at Law depending, desired the Emperour Augustus to come and support him with his Interest: This Prince gave him one of his Attendance to take care of his Business; whereupon the Soldier was so bold as to tell him: Sir, I did not use you the same way; for when you was in danger at the Battel of Actium, I my self fought for you without a Deputy.

Un ancien Soldat ayant un procez à soûtenir, pria l’Empereur Auguste de le venir secourir de son credit. Ce Prince lui donna un de ceux qui l’accompagnoient pour avoir soin de son affaire; là dessus le Soldat fut assez osé pour lui dire: Seigneur, je n’en ai pas usé de la sorte à vôtre égard: quand vous ètiez en danger dans la Bataille d’Actium, moi-même, sans chercher de Substitut, j’ay combatu pour vous.

69

The Poet Simonides asked of Themistocles something contrary to the Laws; he dismist him with these Words: If in thy Poems thou shouldest make Verses without Measures, wouldest thou be accounted a good Poet? And if I should do Things contrary to the Constitution of the Laws, should I be accounted a good Prince?

Le Poëte Simonide demandant à Themistocle quelque chose de contraire aux Loix, il le renvoya avec ce Mot: si dans tes Poemes tu faisois des Vers contre la mesure, passerois tu pour un bon Poëte? Et si je faisois des choses contraires à la disposition des Loix, devroit on m’estimer un bon Prince?

70

The Ambassadours the Athenians had sent to Philip, being returned to Athens, commended that Prince for his Beauty and Eloquence, and his being able to drink much: These Commendations, said Demosthenes, are little worthy of a King; the first of those advantages is proper to Women, the second to Rhetoricians, and the third to Spunges.

Les Ambassadeurs que les Atheniens avoit envoyé vers Philippe, ètant retournez à Athenes, loüoient ce Prince de sa beauté, de son Eloquence, & de sa force à boire beaucoup: Ces loüanges, répondit Demosthene, sont fort peu dignes d’un Roy; le premier avantage est propre aux Femmes, le second aux Rhetoriciens, & le troisiéme aux êponges.

71

Bion being asked whether one should marry a Wife, answered, if you marry an ugly one, you’ll marry a torment; if you take a handsom one, you’ll have a common Woman.

Bion interrogé s’il falloit épouser une Femme, répondit. si vous en prenez une laide, vous épouserez un supplîce; si vous en prenez une belle vous aurez une Femme publique.

72

Hipparchia being desperately in love with Crates the Philosopher, courted him for a Husband, and neither her Relations, nor that Philosopher himself could disswade her from it: But, said Crates to her, do you know what you are in love with? I will be plain with you; Here is your Husband, said he, pulling off his Cloak; then throwing off his Bag and his Stick: Here is, added he, shewing his crooked-back, my Wife’s Jointure; see whether you are contented with it, and whether you can like this way of living. She accepted of all those Conditions, and so he married her.

Hipparchia éperduëment amoureuse du Philosophe Crates, le rechercha en mariage, sans qui ni les Parens, ni ce Philosophe même, pussent la detourner de sa poursuite. Mais, lui dit Crates, connoissez vous bien ce que vous aimez? je ne veux rien vous cacher, voilà l’Epoux, dit-il ôtant son manteau; puis jettant son sac & son baton; voilà, ajoûta-t-il en montrant sa bosse, le Doüaire de ma Femme: Voyez si vous en êtes contente, & si vous pouvez vous accommoder de cette façon de Vie. Elle accepta toutes ces conditions là, & il l’épousa.

73

The Hebrews say that when a Man takes a Wife, he must go down a Step; and that to make a Friend, he ought to go up one; because the one must protect us, and the other be obedient to her Husband.

Les Hebreux disent que pour prendre une Femme, il faut descendre un degré; & que pour faire un ami il faut en monter un; parce qu’il faut que l’un nous protege, & que l’autre obeïsse à son mari.

74

A cowardly and unskilful Wrestler being turned Physician, Diogenes told him: What! have you a mind to lay on the Ground those who used to fling you down?

Un Lâche & mal à droit Luitteur s’ètant fait Medecin, Diogene lui-dit: Hé quoi! vous avez donc envie de coucher par Terre ceux qui vous ont renversé?

75

Alcibiades cut off the Tail of his Dog, which was extraordinary fine, and of great value; and as the People who saw that Dog go about the Streets without a Tail, wondered at the oddness of the thing, he said: I have done it with design that the People talking about this Trifle, may not censure my more important Actions.

Alcibiade coupa la queuë à son Chien, qui ètoit d’une beauté & d’un prix extraordinaire, & comme le Peuple qui voyoit ce Chien marcher en cét état dans les Ruës, s’ètonnoit de cette Bizarrerie, il dit, je l’ai fait afin que le Peuple s’entretenant de cette Bagatelle, ne s’arrête point à controller mes autres Actions plus importantes.

76

Smicythus accused Nicanor of speaking ill of Philip. This Prince who had an esteem for Nicanor, sent for him, and understanding that he was provoked by the Kings not relieving his extream Indigence, he ordered him a Sum of Money. Some time after Smicythus relating to Philip how Nicanor proclaimed his Bounty every where: Well, said he to him, you see we are Masters of our own Reputation, and that we may turn Calumnies into Commendations.

Smicythus accusa Nicanor de parler mal de Philippe. Ce Prince, qui avoit quelque estime pour Nicanor le fit venir, & ayant appris qu’il ètoit indigné de ce que le Roy ne songeoit point à soulager son extreme indigence, il lui fit distribüer quelque somme. Peu de tems aprés Smicythus rapportant à Philippe que Nicanor publioit par tout ses bontez: Hé bien, lui dit-il, vous voyez que nous sommes Maîtres de nôtre Reputation, & que nous pouvons changer toutes les Calomnies en Loüanges.

77

As one asked Zeno whether wise men ought not to love: If wise men did not love, answered he, nothing in the World could be so wretched as the Fair, since none but Fools should be in Love with them.

Comme on demandoit à Zenon si les Sages ne devoient point aimer: si les Sages n’aimoient point, répondit-il, il n’y auroit rien au monde de plus malheureux que les belles, elles ne seroient aimées que des sots.

78

One of Agesilaus his Friends having found him playing with his Children, and riding on a Hobby-horse, seemed to be surprized at it; but the King told him: Pray tell no Body what thou seest till thou hast Children of thy own.

Agesilaüs pour joüer avec ses enfans marchoit à califourchons sur un bâton; un de ses Amis le trouvant en cét état témoigna de la surprise; mais ce Roi, lui dit: je te prie de ne rien dire à personne de ce que tu vois, jusques à ce que tu ayes des Enfans.

79

Philip King of Macedon, designing to make himself Master of a Cittadel, was told by his Spies that the thing was impossible, by reason that there was no way to come at it. Is the way so difficult, asked the King, that a Mule laden with Gold and Silver cannot go to it? and being answered no, then, replied he, it is not impregnable.

Philippe Roi de Macedoine ayant resolu de prendre une Citadelle, les espions lui rapporterent que cela ne se pouvoit pas, parce qu’elle étoit inaccessible. Le chemin, demanda-t-il, est il si difficile qu’on n’y puisse faire entrer un mulet chargé d’Or & d’Argent? & comme ils lui répondirent que non, elle n’est donc pas imprenable, repliqua-t-il.

80

The Night before Darius dispos’d his Troops to the fight, Alexander was in so profound a sleep, that it lasted still several Hours after Sun-rise; his Men frighted at the approach of the Enemies Army, awaked him; and as they wondered at his Tranquility: Be not surprised, said he, at my sleeping so securely: Darius has rid me of a great many Cares, since by gathering this Day all his Forces into one Body, he has given to Valour an opportunity of deciding in one single Battle the fortune of us both.

La Veille que Darius disposa ses troupes au combat, Alexandre dormoit d’un si profond sommeil, qu’il dura encore plusieurs heures aprés le levé du Soliel; ses gens, effrayez de l’armée Ennemie qui s’approchoit l’éveillerent, & comme ils s’étonnoient de sa tranquillité: ne soyez pas surpris, leur dit-il, si je dors si paisiblement: Darius m’a delivré de beaucoup de soucis, puisqu’en ramassant aujourd-hui toutes ses forces en un corps, il a donnê à la valeur le moyen de decider, en un combat, de toute nôtre fortune.

81

Dionysius Tyrant of Syracuse being told that one of his Subjects had buried a Treasure in the Earth, commanded him to bring it to him. The Syracusan gave him but part of it, and having secretly kept the other, he went into another City, where he liv’d more plentifully then he did before; which being related to Dionysius, he restored him the remainder of his Treasure. Now, said he, that he knows how to use riches, he deserves to enjoy them.