Read and listen to the book A Book for the Hammock by Russell, William Clark.

Audiobook: A Book for the Hammock by Russell, William Clark

Project Gutenberg's A Book for the Hammock, by William Clark Russell

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

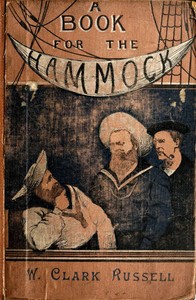

Title: A Book for the Hammock

Author: William Clark Russell

Release Date: January 20, 2020 [EBook #61207]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A BOOK FOR THE HAMMOCK ***

Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

A BOOK FOR THE HAMMOCK

------------------------------------------------------------------------

WORKS BY W. CLARK RUSSELL. Crown 8vo, cloth extra, 6s. each; post 8vo, illustrated boards, 2s. each.

ROUND THE GALLEY FIRE.

ON THE FO’K’SLE HEAD: A Collection of Yarns and Sea Descriptions.

IN THE MIDDLE WATCH.

Crown 8vo, cloth extra, 6s. each.

A VOYAGE TO THE CAPE.

A BOOK FOR THE HAMMOCK.

--------------

THE FROZEN PIRATE, the New Serial Novel by W. CLARK RUSSELL, Author of “The Wreck of the Grosvenor,” began in “Belgravia” for July, 1887, and will be continued till January, 1888. One Shilling, Monthly. Illustrated by P. Macnab.

LONDON: CHATTO AND WINDUS, PICCADILLY.

BY

W. CLARK RUSSELL

AUTHOR OF “A VOYAGE TO THE CAPE,” “ROUND THE GALLEY FIRE,” “IN THE MIDDLE WATCH,” ETC.

[Illustration]

London CHATTO AND WINDUS, PICCADILLY 1887

[The right of translation is reserved]

PREFACE.

The reader will please regard these papers as the mere whiskings of a petrel’s pinions skimming the blue surge of deep waters. The utmost hope of the author goes no further than that here and there something may be found to pleasantly lighten the tedium of a sleepless half-hour in the bunk or hammock, or relieve the dulness of a spell of quarter-deck lounging. The articles are reprinted from The Daily Telegraph, The Gentleman’s Magazine, The Contemporary Review, and Longman’s Magazine. It would have been troublesome to disturb the original text, and some new matter, therefore, has been included in the form of notes.

CONTENTS.

PAGE

A NAUTICAL LAMENT 1 SUPERSTITIONS OF THE SEA 24 OLD SEA ORDNANCE 53 THE HONOUR OF THE FLAG 63 THE NAVAL OFFICER’S SPIRIT 79 WOMEN AS SAILORS 91 FIGHTING SMUGGLERS 104 SEA PHRASES 115 THEN AND NOW 135 COSTLY SHIPWRECKS 146 CURIOSITIES OF DISASTERS AT SEA 157 INFERNAL MACHINES 168 QUEER FISH 179 STRANGE CRAFT 190 MYSTERIOUS DISAPPEARANCES 200 RICH CAPTURES 219 PECULIARITIES OF RIG 230 HOW THE OLD NAVIGATORS MANAGED 243 PLATES AND RIVETS 254 FRENCH SMACKSMEN 273 OLD SEA CUSTOMS 284 WHO IS VANDERDECKEN? 294

A NAUTICAL LAMENT.

I asked myself the question one day whilst standing on the bridge of one of the handsomest and stoutest of the Union Company’s steamboats, outward bound to the Cape of Good Hope, What has become of the old romance of the sea?

“Whither is fled the visionary gleam? Where is it now, the glory and the dream?”

It was a brilliant afternoon. The sunshine in the water seemed to hover there like some flashful veil of silver, paling the azure so that it showed through it in a most delicate dye of cerulean faintness. The light breeze was abeam; yet the ship made a gale of her own that stormed past my ears in a continuous shrill hooting, and the wake roared away astern like the huddle of foaming waters at the foot of a high cataract. On the confines of the airy cincture that marked the junction of sea and sky gleamed the white pinions of a little barque. The fabric, made fairy-like by distance, shone with a most exquisite dainty distinctness in the lenses of the telescope I levelled at it. The vessel showed every cloth she had spars and booms for, and leaned very lightly from the wind, and hung like a star in the sky. But our tempestuous passage of thirteen knots an hour speedily slided that effulgent elfin structure on to our quarter, where she glanced a minute or two like a wreath of mist, a shred of light vapour, and then dissolved. What has become, thought I, of the old romance of the sea? The vanished barque and the resistless power underneath my feet, shaking to the heart the vast metal mass that it was impelling, symbolized one of the most startling realities of modern progress. In sober truth, the propeller has sent the poetry of the deep swirling astern. It is out of sight. Nay, the demon of steam has possessed with its spirit the iron interior of the sailing ship, and from the eyes of the nautical occupants of that combination of ore and wire “the glory and the dream,” that ocean visionary life which was the substance and the soul of the sea-calling of other days, has faded as utterly as it has from the confined gaze of the sudorific fiends of the engine-room.

To know the sea you must lie long upon its bosom; your ear must be at its heart; you must catch and interpret its inarticulate speech; you must make its moods your own, rise to the majesty of its wrath, taste to the very inmost reaches of your vitality the sweetness of its reposeful humour, bring to its astonishments the wonder of a child, and to its power and might the love and reverence of a man. “Enough!” cries Rasselas to Imlac, “thou hast convinced me that no human being can ever be a poet.” And I have convinced myself that the conditions of the sea-life in these times prohibit the most ardent of imaginative sailors from the exercise of that sort of divination which is to be found in perfection in the old narratives. The vocation is too tedious, the stress of it too harassing, the despatch insisted upon too exacting, to furnish opportunity for more than the most mechanical motions of the mind. A man is hurried from port to port with railway punctuality. He is swept headlong through calms and storms, and if there come a pause it will be found perilous; and consternation takes the place of observation. Nothing new is left. The monsters of the deep have sunk into the ooze and blackness of time and lie foundered, waiting for the resurrection that will not come until civilization has run its course and man begins afresh. All seaboards are known; nothing less than an earthquake can submit the unfamiliar in island or coast scenery. The mermaid hugging her merman has shrunk, affrighted by the wild, fierce light of science, and by the pitiless dredging of the deep-water inquirer, into the dark vaults beneath her coral pavilions. Her songs are heard no more, and her comb lies broken upon the sands. Old ocean itself, soured by man’s triumphant domination of its forces, by his more than Duke of Marlborough-like capacity of riding the whirlwind and directing the storm, has silenced its teachings, sleeps or roars blindly, an eyeless lion, and avenges its neglect and submission by forcing the nautical mind to associate with the noblest, the most romantic vocation in the world no higher ideas than tonnage, freeboard, scantlings, well-decks, length of stroke, number of revolutions, the managing owner, and the Board of Trade!

The early mariner was like the growing Boy whom Wordsworth sings of in that divine ode from which I have already quoted—

“But he beholds the light, and whence it flows, He sees it in his joy; The Youth, who daily farther from the East Must travel, still is Nature’s Priest, And by the vision splendid Is on his way attended.”

Were I asked to deliver my sense of the highest poetical interpretation of the deep, I should point into distant times, to some new and silent ocean on whose surface, furrowed for the first time by a fabric of man’s handiwork, floats some little bark with a deck-load of pensive, wondering, reverential men. Yes! you would find the noblest and most glorious divination of the true spirit of the deep in the thoughts which fill the breasts of that company of quaintly apparelled souls. The very ship herself fits the revelation of the sea to those simple hearts who have hardily sailed down the gleaming slope behind the familiar horizon, and penetrated the liquid fastnesses of the marine gods and demons. Mark the singular structure swinging pendulum-like to the respirations of the blue and foamless swell. Her yellow sides throw a golden lustre under her. Little ordnance of brass and black iron sparkle on her bulwarks and grin along her sides. Her poop and top-lanthorns flash and fade with the swaying of her masts. Her pennons enrich the white sails with their dyes, and how long those banners may be let us conceive from that ancient account of the Armada in which it is written: “For the memory of this exploit, the foresayd Captain Banderdness caused the banner of one of these shippes to be set up in the great Church of Leiden in Holland, which is of so great a length, that being fastened to the very roofe, it reached down to the grounde.” Her men are children, albeit bearded, and not yet upon them have the shades of the prison-house begun to close. Are we not to be pitied that all the glories which enraptured them, the wonders which held them marvelling, the terrors which sent them to their devotions, should have disappeared for ever from our sight? We have still indeed the magnificence of the sunset, the splendour of the heavens by night, the Andean seas of the tempest, the tenderness of the moonlighted calm; but these things are not to us as they were to them; for a magic was in them that is gone; the mystery and fear and awe begotten of intrusion into the obscure and unknown principalities of the sea-king have vanished; our interpretation gathers nothing of those qualities which rendered theirs as romantic and lovely as a Shakesperean dream; and though we have the sunset and the stars and the towering surge—what have we not? what is our loss? what our perceptions (staled and pointed to commonplace issues by familiarity) compared with their costly endowment of marine disclosure? You see, the world of old ocean was before them; they had everything to enjoy. It was a virgin realm, also, for them to furnish with the creations of their imagination. The flying-fish! what object so familiar now? The house-sparrow wins as much attention, to the full, in the street as does this fish from the sailor or the passenger as it sparks out from the seething yeast of the blue wave and vanishes like a little shaft of mother-o’-pearl. But in those old times they found a wonder here; and prettily declared that they quitted the sea in summer and became birds. Hear how an old voyager discourses of these be-scaled fowls:

“There is another kind of fish as bigge almost as a herring, which hath wings and flieth, and they are together in great number. These have two enemies, the one in the sea, the other in the aire. In the sea the fish which is called Albocore, as big as a salmon, followeth them with great swiftnesse to take them. This poore fish not being able to swimme fast, for he hath no finnes, but swimmeth with mooving of his taile, shutting his wings, lifteth himselfe above the water, and flieth not very hie; the Albocore seeing that, although he have no wings, yet he giveth a great leape out of the water and sometimes catcheth the fish being weary of the aire.”

It is wonderland to this man. He writes as of a thing never before beheld and with a curious ambition of accuracy, clearly making little doubt that in any case his story will not be credited, and that therefore since the truth is astonishing enough, he may as well carefully stick to it. And the barnacle? Does the barnacle hold any poetry to us? One would as soon seek for the seed of romance in the periwinkle or the crab. Taking up the first dictionary at hand, I find barnacle described as a “shell-fish, commonly found on the bottom of ships, rocks, and timber.” But those wonderful ancient mariners made a goose of it; as may be observed in Mr. John Lok’s account of his ship which arrived home “marvellously overgrowne with certaine shells” in which he solemnly affirms “there groweth a certain slimie substance, which at the length slipping out of the shell and falling in the sea, becometh those foules which we call Barnacles.” Were not those high times for Jack? A barnacle, whether by the sea-side brim or anywhere else, is to us, alas! in this exhaustive age, a barnacle, and nothing more. Or take the maelstrom—a gyration not quite so formidable as the imagination of Edgar Allan Poe would have us believe, but by report exactly one of those features of the ocean to alarm the primitive fancy with frightful ideas: “Note,” says Mr. Anthonie Jenkinson in his voyage to Russia, 1557, “that there is between the said Rost islands and Lofoot a whirlepoole called Malestrand which ... maketh such a terrible noise, that it shaketh the rings in the doores of the inhabitants’ houses of the sayd islands tenne miles off. Also if there cometh any whale within the current of the same, they make a pitiful crie.” And so on. How fine as an artistic touch should we deem this introduction of the whale by the hand of an imaginative writer! The detail to the contemporary readers of Mr. Jenkinson’s yarn would make an enormous horror of that “whirlepoole,” for what should be able to swallow leviathan short of some such stupendous commotion as would be caused by the breaking up of the fountains of the waters of the earth? Let it be remembered that whales were fine specimens in that age of poetry. They were then big enough to gorge a squadron of men-of-war, ay, and to digest the vessels. We have had nothing like them since—the nearest approach to such monsters being the shark in which, on its being ripped open, there was found one full-rigged ship only, with the captain and the mate quarrelling in the cabin over the reckoning.

The age of marine romance supplied the mariner with many extraordinary privileges. We cannot control the winds as those old people did. There are no longer gale-makers from whom Jack can buy a favourable blast. The very saints have deserted us, since it is certain that—at sea—we now pray to them in vain. Observe that in fifty directions, despite our propellers, donkey-engines, steam-windlasses, and the like, the ancient mariner was out and away better off than we are. Did he want wind? Then he had nothing to do but apply to a Finn, who, for a few shillings, would sell to him in the shape of a knotted handkerchief three sorts of gale, all prosperous, but one harder than another, by which he could be blown to his port without anxiety or delay. Did a whirlwind threaten him? Then read in the Voyage of Pirard in Harris’ Collection how he managed: “We frequently saw great Whirl-winds rising at a Distance, called by the Seamen Dragons, which shatter and overturn any Ship that falls in their way. When these appear the Sailors have a Custom of repairing to the Prow or the Side that lies next the storm, and beating naked swords against one another crosswise.” Purchas, in his “Pilgrims,” repeats this, and adds that this easy remedy of the sword hinders the storm from coming over their ship, “and turneth it aside.” Did human skill and judgment fail him? There were the Saints. “Before the days of insurance offices and political economy,” writes the author of “Lusitanian Sketches,” “merchants frequently insured their ships at the highly esteemed shrine of Mantozimbo, by presenting a sum equal to the pay of captain or mate, and that, too, without stipulating for any equivalent should the vessel be wrecked.” Was it not his custom to carry the image of his patron saint to sea with him, to pray to it, to make it responsible for the winds, and, if it proved obstinate, to force it into an obliging posture of mind by flogging it? Consider what a powerful marine battery of these saints he could bring to bear upon the vexed, refractory ocean and the capricious storming of winds. St. Anthony, St. Nicholas, whose consecrated loaves of bread quelled many a furious gale, St. Roland, St. Cyric, St. Mark, St. George, St. Michael, St. Benedict, St. Clement—the list is as long as my arm, the number great enough to swell out a big ship’s company. Did pirates threaten him? There was no occasion to see all clear for action. He had but to invoke St. Hilarion—who once on a time by prayer arrested the progress of a picaroon whilst chasing—and away would scuttle the black flag. Was smooth water required for safely making a port? Then no matter how high the sea ran, all that was needful was first to find a pious man on board, light tapers (where they would burn), bring up the incense, erect a crucifix, read prayers (this being done by the pious man), sprinkle the decks with holy water, and straightway the sea under the vessel’s forefoot would flatten into a level lane, smooth as oil, albeit the surges on either hand continued to leap to the height of the maintop. Who now regards, save with mild curiosity, the corposant—the St. Elmo’s fire—the dimly burning meteoric exhalation at the yard-arm? It is no more to modern and current imagination than the phosphoric flashes in black intertropic waters. But the ancient mariner made an omen of it—a saint—a joy to be blessed; he wrought it into a beneficent symbol, and endowed it with such powers of salvation as comforted him exceedingly whilst he kneeled on quivering knees in the pale illumination of that mystic marine corpse-candle. Who now scratches the mast for a breeze? Who fears the dead body as a storm-maker? What has become of the damnatory qualities of the cat, and who now hears the dimmest echo of comminatory power in her loudest mew? And most galling of all reflections, into what ocean unknown to man has sailed the Flying Dutchman?

Let it not be supposed, however, that the elimination of poetry from the sea-life by the pounding steam engine and the swift voyage is deplorable on no further grounds than these which I have named. The utilitarian aspect is not the only one. There was romance and lustre outside those mere conditions of poetic seamanship which enabled the mariner to direct the wind by a knot, to control the tempest by a candle, to put the pirate to flight by an invocation. Emerge with me from the darkness of remote times into the light of the last—yes, and of the beginning of the present—century. Ladies were then going to sea, as they had in remoter times, dressed as men. They do so no longer. Who ever hears now of some youthful mariner with blooming cheeks and long eyelashes exciting the suspicions of his mahogany-cheeked mates by the shortness of his steps, or the smallness of his hands and feet, or a certain unboyish luxuriance of cropped hair? No, the blushing Pollies and Susans of the East End, resolved by love, by betrayal, or by the press-gang, into the shipping of breeks have had their day. No longer do we read of pretty ship-boys standing confessed as girls. I mourn this departed romantic forecastle feature. Even in fiction how the imagination is captivated by the clever insinuations of the author in his treatment of the youth whose sex he springs upon us presently to our glad surprise! The Edwins whom the Angelinas followed were not indeed very engaging people; but even attentive consideration of their rascalities will not neutralize the pleasant poetic bouquet that haunts the old tales of fine-eyed women going to sea for love or vengeance, living among the sailors, eating the bitter bad provisions of the forecastle, fighting the guns, doing the seamen’s work, and remaining for months undetected.

Again, whither has vanished a feature of the old sea-life even yet more romantically interesting than the nautical masquerading of black-eyed Susans and yellow-haired Molls—the flirtation of the long ocean passage? What we call flirtation now at sea is a mere shadow of a shadow as compared with the robust and solid reality of a period when it took a ship four months to sail to Bombay or Calcutta. There is no time allowed in this age for love-making. Before you can fairly consider yourself acquainted with a girl some wretch on the forecastle is singing out “land-ho!” I took particular notice of this matter on board the Union steamer in which I made the passage home from Cape Town. It must certainly have ended in a proposal in the case of one couple had the propeller dropped off or a boiler burst and the ship been delayed. They only wanted another week. But the steamer was impertinently punctual, about eight hours before her time: the people went ashore at Plymouth, and, for all I can tell, the young man, in the excitement of landing and meeting his friends and seeing plenty of pretty women about, may have abandoned his intention and ended for the girl a chance that would have been a certainty in the old romantic poetical sea-days. Why, we all know how the British matron used to ship her darlings off in the East Indiamen for husbands in the country with which those vessels trafficked, and how scores and scores of these unsophisticated young ladies would land engaged, having affianced themselves to gentlemen on board in calms on the Equator or in the tail of the south-east Trades, or in a small swell with a moderate breeze off Agulhas, some possibly hesitating as far as the Madagascar parallels. How many marriages originate at sea in these times of thirteen knots an hour, I wonder? Out of the several millions of passengers who are annually sea-borne, how many pledge their vows on board ship, how many fall in love there, how many become husband and wife in consequence of meeting on ship board? But a few, I’ll warrant. But only think of the old East Indiaman; four months for Captain Thunder and Miss Spooner to be together to start with; four months, and perhaps longer, with possibly Lieutenant Griffin to give a swift maturity to emotion by importing a neat and useful element of jealousy. Oh, if moonlight and music and feeling are one ashore, what are they at sea, on the deck of a sleeping fabric lifting visionary wings to the lovely stars, when the sea-fire flashes like sheet lightning to the soft surge of the ship’s bows or counter upon the light fold of the invisible swell, when the westering moon, crimsoning as she sinks, wastes her heart’s blood in the deep for love of what she is painfully and ruefully leaving, when the dew upon the bulwarks sparkles like some diamond encrustations to the starlight, when the peace of the richly clad night presses like a sensible benediction upon the breathless, enchanted, listening ship, subduing all sounds of gear-creaking in blocks, of chains clanking to the stirring of the rudder, to a tender music in sweetest harmony with the fountain-like murmur at the bows as the vessel quietly lifts to the long-drawn heave there—think of it! was there ever a bower by Bendemeer’s stream comparable as a corner for the delicate whispers of passion, for the coy reception of kisses, with some quiet nook on the white quarter-deck, shadowed from the stars and protected from the dew by the awning? If you thrill now it is because the whole ship shakes with the whirling and thrashing of those mighty beams of steel below. Emotion must be blatant or it cannot be heard. Not yet has a generation that knows I am speaking the truth in all this passed away. Confirm me, ye scores of elderly master-mariners enjoying your well-earned repose in spots hard by that ocean ye loved and sailed for years! Confirm me too, ye many survivors of a sea-going time, when the most blissful hours of your long and respectable lives were passed under the shadow of the cross-jack-yard!

I lament the decay of the old nautical costumes. There was a poetry in the dress of the people who had the handling of the big Indian ships which you will not get out of the brass buttons and twopenny cuff-rings of the contemporary skipper and mate. Nowadays it is almost impossible to tell the difference between the rigs of the mercantile captain, the dock master, the Customs man, and the harbour master. But what do you say to a blue coat, black velvet lappels, cuffs and collar with a bright gold embroidery, waistcoat and breeches of deep buff, the buttons of yellow gilt, cocked hats, side arms, and so forth? What dress has done for romance ashore we know. Pull off the feathered hats and high boots, the magnificent doublets and diamond buckles of many of those gentlemen of olden times, who show very stately in history, and button them up in the plain frock-coat of to-day, and who knows but that you might not be diverted with a procession of rather insignificant objects? In the poetical days of the sea-profession the ships very honestly deserved the dignity they got from the gilded and velveted figures that sparkled on their quarter-decks. Over no nobler fabrics of wood did the red ensign ever fly. They went manned like a line-of-battle ship. Observe this resolution arrived at by the Court of Directors (Hon. E.I.C.) held the 19th of October, 1791:—“That a ship of 900 tons do carry 110 men; 1000 ditto, 120; 1100 ditto, 125; 1200 ditto, 130.”

Were not those fine times for Jack? How many of a crew goes to the manning of a 1200-ton ship nowadays? And it is proper to note that of these 130 men there were only ten servants, i.e. a captain’s steward, ship’s steward, and men to attend to the mate, surgeon, boatswain, gunner, and carpenter. Contrast these with the number of waiters who swell the ship’s company of our 5000-ton mail boats. Those vessels went armed too, as befitted the majesty of the bunting under which old Dance had gloriously licked Johnny Crapeau.[1] The bigger among them carried thirty-eight eighteen pounders; they were all furnished with boarding-nettings half-mast high and close round the quarters. The chaps in the tops were armed with swivels, musquetoons, and pole-axes. In those romantic times the merchantman saw to himself. There were no laminated plates formed of iron one remove only from the ore betwixt him and the bottom of the ocean; he sailed in hearts-of-oak, and the naval page of his day resounds with his thunder. The spirit of that romantic period penetrated the ladies who were passengers. Relations of this kind in the contemporary annals are common enough:

Footnote 1:

It is interesting to know that Sir John Franklin was in that particular fight, and worked the signals for the Commodore.

“Mrs. Macdowall and Miss Mary Harley, who lately distinguished themselves so much in the gallant defence of the ship Planter, of Liverpool, against an enemy of very superior force off Dover, are now at Whitehaven. These ladies were remarkable, not only for their solicitude and tenderness for the wounded, but also for their contempt of personal danger, serving the seamen with ammunition, and encouraging them by their presence.”

Again: “I cannot omit mentioning that a lady (a sister of Captain Skinner), who, with her maid, were the only female passengers, were both employed in the bread-room during the action making up papers for cartridges; for we had not a single four-pound cartridge remaining when the action ceased.”[2]

Footnote 2:

Many similar notices may be found in the Annual Register, the Naval Chronicle, and other publications of the kind.

The glory and the dream are gone. No doubt there are plenty of ladies living who would manufacture cartridges during a sea-fight with pleasure, and animate the crew by their example and presence. But the heroine’s chance in this direction is dead and over. As dead and over as the armed passenger ship, the privateer, the pirate, and the plate-galleon. Would it interest anybody to know that the Acapulco ship was once more on her way from Manila with a full hold? Dampier and Shelvocke are dead, Anson’s tome is rarely looked into, the cutlass is sheathed, the last of the slugs was fired out of yonder crazy old blunderbuss ages ago; how should it concern us then to hear that the castellated galleon, loaded with precious ore minted and in ingots, with silk, tea, and gems of prodigious value, is under weigh again? Candish took her in 1587, Rogers in 1709, Anson in 1742. Supposing her something more substantial than a phantom, where lives the corsair that should take her now? The extinction of that ship dealt a heavy wound to marine romance. She was a vessel of about two thousand tons burden, and was despatched every year from the port of Manila. She sailed in July and the voyage lasted six months—six months of golden opportunity to the gentlemen who styled themselves buccaneers! The long passage, says the Abbé Raynal, “was due to the vessel being overstocked with men and merchandise, and to all those on board being a set of timid navigators, who never make but little way during the night time, and often, though without necessity, make none at all.” Anson took 1,313,843 pieces of eight and 35,682 oz. of virgin silver out of his galleon, raising the value of his cruise to about £400,000 independent of the ships and merchandise. They knew how to fillibuster in those days. How is it now? It has been attempted of late and found a glorious termination in a police court.

The buccaneer has made his exit and so has his fierce brother, the pirate. That dreadful flag has long been hauled down and stowed away by Davy Jones in one of his lockers. “The pirates,” says Commodore Roggewein in 1721, “observing this disposition, immediately put themselves in a fighting posture; and began by striking their red, and hoisting a black flag, with a Death’s Head in the centre, a powder-horn over it, and two bones across underneath.” Alas! even the sentiment of Execution Deck has vanished with the disappearance of this romantic flag, and there are no more skeletons of pirates slowly revolving in the midnight breeze and emitting a dismal clanking sound to the stirring of the damp black gusts from which to borrow a highly moving and fascinating sort of marine poetry.

Again, though to be sure it is not a little comforting when in the middle of a thousand leagues of ocean to feel that your ship is navigated by men furnished with the exquisite sextant, the costly chronometer, the wonderful appliances for an exact determination of position, yet there is surely less poetry and romance in the nautical scientific precision of the age, reconciling as it undoubtedly is—particularly when you are afloat—than in the old shrewd half-blind sniffing and smelling out of the right liquid path by those ancient mariners who stumbled into unknown waters, and floundered against unconjecturable continents with nothing better to ogle the sun with than a kind of small gallows called a fore-staff.

“If,” writes Sir Thomas Browne to his sailor son in 1664, “you have a globe, you may easily learne the starres as also by bookes. Waggoner[3] you will not be without, which will teach the particular coasts, depths of roades, and how the land riseth upon several poynts of the compasse.... If they have quadrants, crosse-staffes, and other instruments, learn the practicall use thereof; the names of all parts and roupes about the shippe, what proportion the masts must hold to the length and depth of a shippe, and also the sayles.”

Footnote 3:

Wagenar’s “Speculum Nauticum,” Englished in 1588.

Here we have pretty well the extent of a naval officer’s education in navigation and seamanship in those rosy times. The longitude was as good as an unknown quantity to them. How quaint and picturesque was the old Dutch method of navigating a ship! They steered by the true compass, or endeavoured to do so by means of a small central movable card, which they adjusted to the meridian, and whenever they discovered that the variation had altered to the extent of 22 degrees, they again corrected the central card. In this manner they contrived to steer within a quarter of a point, and were perfectly satisfied with this kind of accuracy. They never used the log, though it was known to them. The officer of the watch corrected the leeway by his own judgment before marking it down. J. S. Stavorinus, writing so late as 1768–78, says, “Their manner of computing their run is by means of a measured distance of forty feet along the ship’s side. They take notice of any remarkable patch of froth when it is abreast of the foremost end of the measured distance, and count half seconds till the mark of froth is abreast of the after end. With the number of half seconds thus obtained they divide the number forty-eight, taking the product for the rate of sailing in geographical miles in one hour, or the number of Dutch miles in four hours. It is not difficult,” he adds, “to conceive the reason why the Dutch are frequently above ten degrees out in their reckoning.” Here we have such a form of Arcadian simplicity, if anything maritime can borrow that pastoral word, as cannot fail to excite the enthusiasm of the romancist. A like delightful and fascinating primitiveness of sea-procedure you find in Mr. Thomas Stevens’ black-letter account of his voyage; wherein he so clearly sets forth the manner of the navigation of the ancient mariner, that I hope this further extract from other people’s writings will be forgiven on the score of its curiousness, and the information it supplies:—

You know that it is hard to saile from East to West or contrary, because there is no fixed point in all the skie, whereby they may direct their course, wherefore I shall tell you what helps God provided for these men.[4] There is not a fowle that appereth, or signe in the aire, or in the sea, which they have not written, which have made the voyages heretofore. Wherefore, partly by their own experience, and pondering withal what space the ship was able to make with such a winde, and such direction, and partly by the experience of others, whose books and navigations they have, they gesse whereabouts they be, touching degrees of longitude, for of latitude they be alwaies sure.

Footnote 4:

That is, for the mariners with whom he sailed.

“Gesse whereabouts they be!” The true signification of this sentence is the revelation of the fairy world of the deep. It was this “gessing,” this groping, this staring, the wondering expectation, that filled the liquid realm with the amazements you read of in the early chronicles. It would not be delightful to have to “gess” now. It could hardly mean much more than an unromantic job of stranding, a bald prosaic shipwreck, with some marine court of inquiry at the end of it, to depress the whole business deeper yet in the quagmire of the commonplace. But attached to the guesswork of old times was the delightful condition of the happening of the unexpected. The fairy island inhabited by faultless shapes of women; fish as terrible as Milton’s Satan; volcanic lands crimsoning a hundred leagues of sky with the glare of the central fires of the earth, against whose hellish effulgent background moved Titanic figures dark as the storm-cloud—of such were the diversions which attended the one-eyed navigation of the romantic days. Who envies not the Jack of that period? Why should the poetic glories of the ocean have died out with those long-bearded, hawk-eyed men? I can go now to the Cape of Good Hope—in a peculiar degree the haunt of the right kind of marvels, and the headland abhorred by Vanderdecken—I can steam there in twenty days, and not find so much as the ghost of a poetical idea in about six thousand miles of ocean. Everything is too comfortable, too safe, too smooth. There is the same difference between my mail-boat and the jolly old carrack as there is between a brand-new hotel making up eight hundred beds and an ancient castle with a moated grange. What fine sights used to be witnessed through the windows of that ancient castle! Ghosts in armour on coal-black steeds, lunatic Scalds bursting into dirges, an ogre who came out of the adjacent wood, dwarfs after the manner of George Cruikshank’s fancies—in short, Enchantment that was substantial enough too. But the brand-new hotel! Why, yes, certainly, I would rather dine there, and most assuredly would rather sleep there, than in the moated-grange arrangement. What I mean is: I wish all the wonders were not gone, so that old ocean should not bare such a very naked breast.

Observe again how elegant and splendid those ancients were in their sea notions. When they built a ship they embellished her with a more than oriental splendour of gold and fancy work. Read old Stowe’s description of the Prince Royal: how she was sumptuously adorned, within and without, with all manner of curious carving, painting, and rich gilding. They had great minds; when they lighted a candle it was a tall one. How nobly they brought home the body of Sir Philip Sydney, “slaine with a musket-shot in his thigh, and deceased at Arnim, beyond seas!” The sails, masts, and yards of his “barke” were black, with black ancient streamers of black silk, and the ship “was hanged all with black bayes, and scorchions thereon on pastboard (with his and his wyfes in pale, helm and crest); in the cabin where he lay was the corpse covered with a pall of black velvet, escochions thereon, his helmet, armes, sword, and gauntlette on the corpse.” In the regality of the names they gave their ships there is a fine aroma of poetry: Henri-Grace-a-Dieu, the Soverayne-of-the-Seas, the Elizabeth-Jonah, the Jesus-of-Lubeck, the Constant-Warwick! The genius of Shakespeare might be thought to have presided over these christenings if it were not for the circumstance of numberless squadrons of sweetly or royally named ships having been launched before the birth of the immortal bard; and a list of them harmonised into blank verse would have the organ-sounds delivered by his own great muse.

The visionary gleam has fled; the glory and the dream are over. Yes, and the prosaics of the sea have entered into the sailor’s nature and made a somewhat dull and steady fellow of him, though he will shovel you on coals as well as another, and pull and haul as heartily as his forefathers. For where be his old caper-cutting qualities? Where be the old high jinks, the Saturday night’s carouse, the pretty forecastle figment of wives and sweethearts, the grinning salts of the theatre-gallery, the sky-larking of liberty days, the masquerading humours, such, for example, as Anson’s men indulged themselves in after the sacking of Paita, when the sailors took the clothes which the Spaniards in their flight had left behind them, and put them on—a motley crew!—wearing the glittering habits, covered with yellow embroidery and silver lace, over their own dirty trousers and jackets, clapping tie and bagwigs and laced hats on their heads; going to the length, indeed, of equipping themselves in women’s gowns and petticoats; so that, we read, when a party of them thus metamorphosed first appeared before their lieutenant, “he was extremely surprised at the grotesque sight, and could not immediately be satisfied they were his own people.” They were a jolly, fearless, humorous, hearty lot, those old mariners, and their like is not amongst us to-day. The sentiment that prevailed amongst them was in the highest degree respectable.

“Yes, seamen, we know, are inured to hard gales; Determined to stand by each other; And the boast of the tar, wheresoever he sails, Is the heart that can feel for another!”

And has not the passenger degenerated too? Is he as fine and enduring a man as his grandfather? is she as stout-hearted as her grandmother? The life of a voyager in the old days of the sailing-ship—I do not include John Company’s Indiamen—was almost as hard as that of the mariner. He had very often to fight, to lend a hand aloft, at the pumps, at the running rigging. His fare was an unpleasant kind of preserved fresh meat—I am speaking of fifty years ago—and such salt pork and beef as the sailors ate. His pudding was a dark and heavy compound of coarse flour and briny fat, and in the diary of a passenger at sea in 1820 it is told how the puddings were cooked: “July 16. As a particular favour obtained a piece of old canvas to make a pudding-bag, for all the nightcaps had disappeared. The pudding being finished, away it went to the coppers, and at two bells came to table smoking-hot. But a small difficulty presented itself; for then, and not till then, did we discover that the bag was smaller at top than at bottom, so that, in spite of our various attempts to dislodge it, there it stuck like a cork in a bottle, till every one in the mess had burnt his fingers, and then we thought of cutting away the canvas and liberating the pudding.” Such experiences as this made a hardy man of the passenger. There was no coddling. Everything was rough and rude; yet read the typical passenger’s writings and you will see he found such poetry and romance in the ocean and the voyage as must be utterly undiscoverable by the spoilt and languid traveller of to-day, sulkily perspiring over nap or whist in the luxurious smoking-room, or reading the magazine—that outruns its currency by a week only in a voyage to New Zealand—propped up by soft cushions in a ladies’ saloon radiant with sunshine and full of flowers. Like the early Jack, the early passenger came comparatively new to the sea and enjoyed its wonders and revelled in its freedom and drank in its inspirations. He was not to be daunted by food, by wet, by delay, by sea-sickness, by coarse rough captains. Why, here before me, in the same passenger’s diary in which the above extract occurs, I find the writer distinctly noting the picturesque in that most hideous of maritime calamities, want of water! “July 2. All hands employed catching rain water, the fresh water having given out. ’Twas interesting and romantic to see them running fore and aft with buckets, pitchers, jars, bottles, pots, pans, and kegs, or anything that would hold water. I was quietly enjoying the scene, when the clew of the mainsail above me gave way from the weight of water that had collected there, and I received the whole contents on my devoted head.” Quietly enjoying the scene! Is not this a very sublimation of the heroic capacity of extracting the Beautiful—not in the Bulwerian sense—out of the Dreadful!

But enough! Just as you seek for the romance and poetry of the ocean in the old books, so must you look there for the jovial tar, the jigging fellow, with his hat on nine hairs and a nose like a carbuncle; for the resolved and manly passenger, for the unaffected heroine, for the pretty masquerading lass, and for a hundred lovely gilded dreams of a delighted imagination roving wild in mid-ocean. The volume is closed; we now carry our helm amidships; it is no longer the captain but the head engineer that we think of and address ourselves to when, disordered by some inward perturbation, we sing:—

“O, pilot, ’tis a fearful night, There’s danger on the deep.”

But Philosophia stemma non inspicit; and we must take it that in these days she knows what she is about.

SUPERSTITIONS OF THE SEA.

There is a story told of some English sailors who, passing by the French Ambassador’s house, that was illuminated in celebration of a treaty of peace between France and Great Britain, observed the word “Concord” flaming in the midst of several devices. The men read it “Conquer’d,” and one of them exclaiming, “They conquer us! they be,” etc., they knocked at the door and demanded to know why such a word was put up. The reason was explained, but to no purpose, and the French Ambassador, in order to get rid of these jolly tars, ordered “Concord” to be taken down and replaced by the word “Amity.”

It is to illiteracy of this kind that we are indebted for much of the romantic superstitions of the sea. In olden days the forecastle was certainly very unlettered, and the wonderful imaginings of the early navigators, whose imperfect gaze and enormous credulity coined marvels and miracles out of things we now deem in the highest degree prosaic and commonplace, descended without obstruction of learning or scepticism through the marine generations. It is easily seen on reading the old sea-chronicles how most of the superstitions had their birth, and it needs but a very superficial acquaintance with the nautical character to understand why they should have been perpetuated into comparatively enlightened times. Two capital instances occur to me, and they are both to be found in the narrative of Cowley’s voyage round the world in the years 1683, ’84, ’85, and ’86. The first relates to the old practice of choosing valentines.

“We came abreast with Cape Horn,” says the author, “on Feb. 14, 1684, where we chusing of valentines, and discoursing of the intrigues of women, there arose a prodigious storm, which did continue to the last day of the month, driving us into the latitude of 60 deg. and 30 min. south, which is further than any ship hath sailed before south; so that we concluded the discoursing of women at sea very unlucky, and occasioned the storm.” That such a superstition as this ever obtained a footing among mariners I will not declare. Yet it is easily seen that the conclusion the author arrived at, that the “discoursing of women at sea” is very unlucky, might engender a superstition strong enough to live through centuries. In the same book is recounted another strange matter, of a true hair-stirring pattern. On June 29, 1686, there had been great feasting on board Cowley’s ship, and when the commanders of the other vessels departed they were saluted with some guns, which, on arriving on board their ships, they returned. “But,” says the author, “it is strangely observable that whilst they were loading their guns they heard a voice in the sea crying out, ‘Come, help! come, help! A man overboard!’ which made them forthwith bring their ships to, thinking to take him up; but heard no more of him.” The captains were so puzzled that they returned to Cowley’s ship to see if he had lost a man; but “we nor the other ship had not a man wanting, for upon strict examination we found that in all the three ships we had our complement of men, which made them all to conjecture that it was the spirit of some man that had been drowned in that latitude by accident.” Thus they resolved their perplexity, braced up their yards, and pursued their course in a composed posture of mind; and in this easy way I think was a large number of the superstitions, which fluttered the forecastle and perturbed the lonely look-out man, generated.

So of the corposant, that ghostly meteoric exhalation, which in gales of wind or in dead calms blazes at the end of yards, or hovers in bulbous shinings upon the mastheads. One readily sympathizes with the old superstitions here. To the ancient mariner it could be nothing else than some spirit hand issuing out of the dusk that kindled those magic lamps. What should they portend to the startled hearts of the Columbian and Magellanic sailors lost in the deepest solitudes of oceans whose wastes their keels were the first to furrow? Happily they were found propitious, and superstition devised a saintly origin for them. “On Saturday,” we read in the second voyage of Columbus, “at night, the body of St. Elmo was seen, with seven lighted candles in the round top, and there followed mighty rain and frightful thunder. I mean the lights were seen which the seamen affirm to be the body of St. Elmo, and they sang litanies and prayers to him, looking upon it as most certain that in these storms, when he appears, there can be no danger.”[5] The sign that admits of an auspicious interpretation is always useful. The most literal-minded of men even in these days of hard facts is pleased when something befalls him which people say is a sign of good luck. There is a famous instance of a ship having been saved by allowing a Lascar to discharge a superstitious obligation by securing a bag of rice and a few rupees in the rigging as a votive offering to some hobgoblin. His black companions, worn out with pumping, had tumbled down into the scuppers, saying that the ship was doomed, and heaven must have its way; but when the Lascar descended the rigging and pointed to the bag swinging up there, they cried out for joy, fell to the pumps till they sucked, and enabled the master to carry his ship home. That stout old buccaneer, Dampier, tells of a tempest in the midst of which a corposant flamed out from the masthead. “The sight rejoiced our men exceedingly,” says he; “for the height of the storm is commonly over when the Corpos Sant is seen aloft, but when they are seen lying on the deck, it is generally accounted a bad sign.” Anything that heartens men in extremity is good; and in olden times there were superstitions aboard ship which did more for the salvation and deliverance of mariners than all the rum punch that was ever swallowed out of capacious jacks.

Footnote 5:

Erasmus in his Dialogues, tells of a certain Englishman who, in a storm, promised mountains of gold to our Lady of Walsingham if he touched land again! Another fellow promised St. Christopher a wax candle as big as himself. When he had bawled out this offer, a man standing near said, “Have a care what you promise, though you make an auction of all your goods you’ll not be able to pay.” “Hold your tongue,” whispered the other, “you fool! do you think I speak from my heart? If once I touch land I’ll not give him a tallow candle!” Cardinal de Retz in describing a storm says, “A Sicilian Observantine monk was preaching at the foot of the great mast, that St. Francis had appeared to him and had assured him that we should not perish.”

One might go even further, and commit an apparent indiscretion by declaring that—so far as the sea goes—there may even be a virtue in lies. A vast amount of early marine enthusiasm is due to fibbing. The amazing yarns the old voyagers spun on their return sent others off in hot haste; and they took care not to come back without a plentiful stock of more exciting tales yet. Distinct impulse was given to Arctic exploration by an old Dutchman’s grave, schnapps-smelling twister. The story is told by Mr. Joseph Moxon,[6] who, in the seventeenth century, was member of the Royal Society. “Being about twenty-two years ago in Amsterdam,” says he, “I went into a public house to drink a cup of beer for my thirst, and sitting by the public fire among several people, there happened a seaman to come in, who, seeing a friend of his there who he knew went in the Greenland voyage, wondered to see him, for it was not yet time for the Greenland fleet to come home; and asked him what accident brought him home so soon.” This question the other answered by saying “the ship went not out to fish as usual, but only to take in the lading of the whole fleet,” and that “before the fleet had caught fish enough to lade us, we, by order of the Greenland Company, sailed unto the North Pole and came back again.” This greatly amazed Mr. Joseph Moxon, of the Royal Society, and he earnestly questioned the man, who declared that he had sailed two degrees beyond the pole, and could produce the whole body of sailors belonging to the ship to prove it. “I believe this story,” says the Royal Society man, and he delivers it to the world as a fact, disproving all that has been recorded by the Frobishers, the Willoughbys, the Davises, and the rest of those who had steered north. One Dutchman may give rise to many superstitions—does not the world owe the legend of the Phantom Ship to the Batavian genius?—and who shall tell the extent of the impulse contained in the fable of an old Dutch whaleman yarning over a cup of beer in an Amsterdam ale-house?

Footnote 6:

In Harris’s Collection.

It is not clear, however, that any possible good can result from such marine credulity as that to which that notable prodigy, for instance, called the sea-serpent owes what life it has. It is interesting indeed to find one of the most amazing of the ancient myths vital in forecastles some thousands of years younger than the legend; but it is not evident that the Kraken, the Leviathan, the Titanic worm that dieth not, the monstrous snake of the deep, ever led the way into a wholesome and worthy issue, such as the discovery of lands or of fishermen’s hunting-fields.[7] How often the sea-serpent has been seen it would be hard to say. If there be weight in human testimony there are surely witnesses enough to its existence. Dr. Samuel Johnson could not have pointed to a larger cloud of testifiers in favour of those shadowy beings which he believed in. “All seamen,” says Olaus Magnus in his “History of the Goths,” “say there is a sea-serpent two hundred feet long and twenty feet thick, who comes out at night to devour cattle. It has long black hair hanging down from its head, and flaming eyes, with sharp scales on its body.” Other early writers describe its body as resembling a string of hogsheads, and affirm it to be at least six hundred feet long. Sir Walter Scott, who found the tradition he speaks of among the Shetland and Orkney fishermen, speaks of the sea-snake as a monster that rises out of the depth of the ocean, stretches to the skies his enormous neck covered with a mane like that of a war-horse, and “with his broad glittering eyes raised mast high, looks out as it seems for plunder or for victims.”

Footnote 7:

“The steward relates,” I find in a book of travels, “that in a vessel he once sailed in, a hand aloft asserted that he saw land ahead. The captain knew this to be a mistake; and on nearing it the land turned out to be the carcase of a huge whale left by the fishery, with a number of albatrosses preying on it.”

A writer in the British Merchant Service Journal in 1879 seems to have satisfactorily solved this perplexing ocean enigma. He saw the sea-serpent three times. First in 1851, during a voyage to Tasmania. The terrifying wonder lay right in the ship’s path, but the captain would not shift his helm, with the result that he sailed close past a long log of wood covered with barnacles of great length—“so long that, being attached to the logs, they necessarily took all the undulations of the waves, which gave it the appearance of a sinuous motion.” Again, in 1853, bound for the Cape of Good Hope; the monster lay on the weather bow with his capacious jaws open; but for the second time the creature proved no more than the trunk of an old tree, a branch of which nicely expressed the beast’s jaw. Once again in 1869, this time in seven degrees north of the equator; on this occasion the serpent exhibited long, sleek, variegated sides as the sun shone upon him. “He turned out the veriest old buck of a sea-serpent I have met with in my long career at sea. There he lay alongside from eleven a.m. until nine p.m., unable to leave such good company (we had many passengers from New Zealand); but he left with us, in token of his great regard, 186 fine large rock cod, averaging at least five pounds each. We hoped to meet him again, although he was only an old log of timber.”

Many curious sea superstitions can be traced to noises which, when heard by the old navigators, were found unusual and terrifying. There is a curious passage bearing on this in the voyage of J. S. Stavorinus to the East Indies in 1768. He heard a sound just like the groaning of a man out of the sea, near the ship’s side. It was repeated a dozen times over, but seemed to recede proportionally as the ship advanced until it died away at the stern. An hour afterwards the gunner came to the author and said that on one of his Indian voyages he had met with the same occurrence, and that a dreadful storm had succeeded, which forced them to hand all their sails and drive at the mercy of the wind for twenty-four hours. The author adds that when the gunner told him this there was no sign of bad weather, yet before four o’clock in the afternoon they were scudding under bare poles before a violent tempest. Upon so singular an experience the sufferers might claim a right to base a superstition; and from that time any sound resembling that of a man bawling in the water over a ship’s side must take a barometrical character, and prove an exhortation to the mariner to see all snug.

The nervous system need be suffering from no debilitation of superstition to find in the approaching and bursting of the cyclone much that is too terrific to leave room for the display of the qualities of sublimity, though than these revolving tempests few passionate outbreaks of nature yield more. First there is the alarming indication of the barometer, with the slow and sullen glooming over of the heavens, the wan and beamless aspect of the sun or moon, the light of all the stars—even to the most piercing of the planets—being shrouded, along with the sulky heaving of the sea, whose oppressed breathing, as it comes in clogged and thickish draughts of air from the slope of each sullen fold will often be charged with a weedy, fish-like, and decaying odour. Then there is the noise of the approaching storm, that has been described as a rising and falling sound, of a moaning and complaining nature, as though the nearer deep were something sentient and crying to be hidden from the coming furious tormentor. Some have it that this melancholy and malignant echo may be heard as far off as two hundred miles, that it is caused by the actual raging of the hurricane at that distance, and that it is not directly borne to the ear by the wind, but obliquely reverberated by the clouds. A single sentence written by a sailor taking his notes from nature will have in it a suggestion of the ominousness of storm-imports beyond the reach of the finest imaginative description, as, for instance, when the captain of the ship Ida, quoted by Reid, in his interesting work, says: “Fresh gales and squally weather; at four, handed the foretopsail and foresail; at intervals the wind came in gusts, then suddenly dying away, and continued so for four hours.” Here, in a sentence, is fully described the advent of the cyclone, leaving to the fancy to make out for itself all that is comprised of expectation, watchfulness, and even fear in the dull and sudden dying away of the gusts and the silence of the four hours following. Then enter, very often, other formidable conditions, features of livid magnificence, and oppressive because of the confusion they import into aspects of nature familiar to the eye. Of such are the red skies, not the strong westerly glowings following the sinking of the sun, but spaces of blood red witnessed in the midnight zenith, sheets of purple splendour in the east and the like. One testimony speaks of a crimson sky beheld late at night both east and west, for three days before the gale came down; another of the sky catching a red light at sunset, and continuing to glow all over, as though incandescent till past midnight, the smooth breast of the sea reflecting the frightful and wondrous irradiation, so that the ship seemed to rest upon a floor of fire with a red-hot dome above. When finally the storm bursts, it comes in the manner faithfully described in “Purchas,” in the passage referring to the tempest that wrecked one hundred Spanish ships at Tercera: “This storme continued not onely a day or two with one winde, but seven or eight days continually, the winde turninge round about in all places of the compasse at the least twice or thrice during that time, and all alike with a continuall storme and tempest most terrible to beholde, even to us that were on shore much more then to such as were at sea.” In weather-aspects of the cyclonic kind we may safely seek for the origin of many a wild superstition of the ship and the sailor.

Amongst the most enduring of salt superstitions are those connected with the wind. In a dead calm to whistle for a breeze is but one illustration of an ever-abiding faith. “Scratch the foremast with a nail: you will get a good breeze,” is among forecastle saws and instances. You may raise the wind, too, by sticking a knife into the mizzen-mast, taking care that the haft points to the quarter whence you desire the breeze to blow. The cat, as we all know, is a sort of wind-broker. It is believed that pussy carries a gale in her tail. To throw a cat overboard is a storm-prescription never known to fail. In some parts of the north of England it is said it was a custom for sailors’ wives to keep a black cat in the house as a guarantee of their husband’s safety whilst away. At the same time it is a cherished article of Jack’s creed that if you have a cat on board and a heavy storm arises you may appease the wrath of the Fiend of the Weather by throwing the cat into the sea.

Wonderful stories are related of people who sold winds. Baxter, in his “World of Spirits,” gravely tells of an old parson, who, before being hanged, confessed that he had two imps, one of which “was always putting him on doing mischief, and (being near the sea) as he saw a ship under sail it moved him to send him to sink the ship, and he consented and saw the ship sink before him.” This imp would have done better had he advised the parson to sell the winds. The mariner was a credulous creature then, and a prosperous gale to the Spice Islands was surely worth more ducats than a cure of souls was likely to yield. Of all the wind-brokers mentioned in history the Russian Finn has ever been accounted the most famous. In a narrative of a voyage to the north, included in Harris’s voluminous collection, it is excellently told how the master of the ship in which the author of the narrative sailed, finding himself beset with calms and baffling airs on the coast of Finland, agreed to buy a prosperous wind from a wizard. The price was ten Kronen, about one pound sixteen shillings, and a pound of tobacco. The wizard presented the skipper with a woollen rag containing three knots, the rag to be attached to the foremast. Each knot held a gale of wind, the third rising to a tempest “so furious that we thought the heavens would fall down upon us; and that God would justly punish us with destruction for dealing with infernal wizards, and not trusting to his providence.” So recently as 1857 a sailor was tried for the murder of a mulatto, the man’s defence being that he thought the coloured fellow a Finn, and so put him out of the way of doing harm. In “Two Years Before the Mast” Dana has stated the case of the Finn delightfully, by representing a sea-cook and an old ignorant sailor talking of a wizard they knew; how he raised an unfavourable wind until the captain starved him into shifting the breeze by locking him up in the forepeak; how he got drunk every night on a bottle of rum, which, nevertheless, remained full throughout the voyage; and so forth. The capriciousness of the wind renders it a very suitable agency for diabolic influence. The causes which stagnate or fix it in an unfavourable quarter are wonderfully numerous. Holcroft, the comedian, tells us in his memoirs that during a trip to Sunderland the sailors, knowing him to be an actor, concluded that he must therefore be a Jonah. Happening on an Easter Sunday to be walking the deck with a book in his hand, he was approached by some seamen, who advised him to read a prayer-book, instead of a book of plays. “By the Holy Father!” cried one of them; “I know you are the Jonas; and by Jasus the ship will never see land till you are tossed overboard—you and your plays wid ye.” The origin of Jack’s notorious objection to sailing with a parson on board probably lies in the old superstition that the devil, who is the greatest of storm raisers, hates priests, and whenever he can catch one at sea will send a storm to destroy him.

It is not very long ago (1886) that the people on board a ship which was then off the Horn, running before a small westerly gale, noticed an immense albatross following in the vessel’s wake. This bird clung so obstinately to the skirts of the running ship that its identity became, in a day or two, a distinguishable thing amongst the other sea-fowl of a like kind that pursued the vessel. One day, as this huge bird was hovering at a short elevation above the taffrail, it was noticed that an object about the size of a dollar was suspended from its neck. Glasses were brought to bear, but nothing could be made of the great bird’s embellishment. Thereupon everybody grew eager to catch the creature, and a hook was forthwith baited with a piece of pork and towed astern. Some of the other albatrosses were caught, but the desired one was not to be entrapped. It would sail with a sweep to over the bait that hissed through the water, poise itself on a magnificent length of tremulous pinion, whilst its eyes, glowing like Cairngorm stones, inspected the greasy dainty, and then, with a scream that might have passed very well for an expression of scorn, slide away athwart the path of the wind, and fall to its old gyrations, narrowing down at last into steady pursuit.

But on the third day the noble fowl took the hook, and was triumphantly dragged on board, straining and flapping like a huge Chinese kite in a squall. It was then found that the object hanging at its neck was a brass pocket-compass case, secured to the bird by three stout strands of copper wire. Two of these wires had been severed by wear, and the box itself was thickly coated with verdigris. On opening it a piece of paper was discovered on which was written in faded ink, “Caught May 3, 1848, in lat. 38 deg. S. 40 deg. 14 min. W., by Ambrose Cocharn, of American ship Columbus.” A fresh label, with the old and new dates of capture, was fastened round the bird’s neck, and the great seagull was then released. Before the men let the bird fly they measured its wings, and found them to be 12 ft. 2 in. between the tips. It is perfectly reasonable to assume, with the captors, that this albatross, when taken and labelled by the people of the American ship Columbus, was four or five years old, and the story, therefore conclusively proves that the natural life of these birds is at least fifty years, though how much longer they may go on living after that period is attained has yet to be determined. For thirty-eight years this bird had been flying about with a brass pocket-compass case dangling at its throat! A writer once calculated the distance traversed by a little pilot-fish that accompanied the vessel he was in. It joined the ship off the Cape de Verd Islands, and it followed her right away round Cape Horn to as far as Callao; the whole distance accomplished having been about 14,000 miles, the time 122 days, showing a daily average of 115 miles.[8] But what should be thought of the leagues covered by that winged postman of the old Yankee ship Columbus in a flight extending over a period of thirty-eight years?

Footnote 8:

Davis, in the “Nimrod of the Seas,” a finely-told whaling story.

It is somewhat strange that Cornelius Vanderdecken, the well-known if not popular commander of the Flying Dutchman, should never have used the seabird as a messenger to his wife and children in old Amsterdam. It is part and parcel of his unhappy destiny that he shall not be able to persuade sailors to carry a letter home for him, Jack very well knowing that, airy as may be one of these phantom missives, it has weight enough of fatality in it to sink his ship. It was an old custom among seamen on catching an albatross to secure a bundle of letters for wives and sweethearts under his wing and despatch him with a loud hurrah. Not impossibly his usefulness in this direction may have suggested that his presence signified good luck.

“At length did cross an albatross. Through the fog it came, As if it had been a Christian soul We hailed it in God’s name.”

So sings the Ancient Mariner, with this result:

“And a good south wind sprung up behind. The albatross did follow.”

The famous old buccaneering skipper Shelvocke writes, in his voyages, “We had not the sight of one fish of any kind since we were come to the south-west of the Straits of Le Maire, nor one sea-bird, except a disconsolate black albatross who accompanied us several days, hovering about us as if he had lost himself, until Sam Huntley, my second officer, observed in one of his melancholy fits that the bird was always hovering near us, and imagined from its colour that it might be an ill-omen, and, being encouraged in his impression by the continued season of contrary weather which had opposed us ever since we had got into these seas, he, after some fruitless attempts, shot the albatross.”

Who will question that in those olden times of marine superstitions the mariners of Shelvocke attributed the failure of their expedition to the shooting of that disconsolate fowl? But these birds do not appear to have inspired maritime fancy to any marked degree. The belief of old sailors that if an albatross be slaughtered it at once becomes necessary to keep one’s “weather eye lifting” for squalls, but that no harm follows if the bird be caught with a piece of fat pork, and is allowed to die a “natural” death on deck, about sums up the traditionary apprehensions in respect of the bird. Yet this meagreness of forecastle imagination is strange, for assuredly the albatross is the pinioned monarch of the deep, the majestic and beautiful eagle of the liquid, foam-capped crags and steeps of the ocean, and will for days so haunt the wakes of ships as to impart just that element of the familiar into the wild and desolate freedom of the cold grey skies and snow-swept billows of dominion which especially fertilizes the fancy of the mariner, who needs something of the prosaic to hold on by just in the same way that he swings by a rope high aloft in the middle air.

Nevertheless it is true that there are scores of comparatively insignificant sea and land birds whose feathers are supposed to cover larger powers for good or evil than even the spacious-winged albatross.

The common house-sparrow: here surely is a strange little fowl of the air to parallel, nay to surpass the wizard powers of the shrieking monarch of the Horn and the Southern Ocean; and yet it is gravely asserted that should sparrows be blown away to sea and alight upon a ship they are not to be taken or even chased, for in proportion as the birds are molested must sail be shortened to provide against the storm that will certainly come. In the interests of humanity nothing could be better than such superstitions. The harmless and beautiful gull, whose lovely sweepings and curvings through the air, whose exquisite self-balancing capacity in the teeth of a living gale, whose bright eyes, salt, shrewd voice, and webbed feet folded in bosom of ermine, it is impossible to sufficiently admire, though there be unhappily no lack of sea-side Nathaniel Winkles who regard this pretty creature as a mark set up by Nature for cockneys to shoot at, has a commercial virtue that sets it high in the long shoreman’s catalogue of things to be approved; for when this bird appears in great numbers then is its presence accepted as an infallible sign of the neighbourhood of herring shoals.

Herman Melville has somewhere said that in his time it was reckoned a bad omen for ravens to perch on the mast of a ship, at the Cape of Good Hope. We know that the raven himself was hoarse that croaked the fatal entrance of Duncan, and there is no reason, no forecastle reason at least, why the Storm-Fiend should not have ravens harnessed to his chariot after the manner of the doves of Venus, though why these plumed steeds are peculiarly obnoxious to mariners at or off the Cape of Good Hope is not certainly known.

It was an old superstition that the rotten timbers of foundered ships generated birds.[9] “When,” says a very Early English naturalist, “this old wrack of ships falls in the sea, it is rotted and corrupted by the sea, and from this decay breeds birds, hanging by the beaks to the wood; and when they are all covered with plumage and are large and fat, then they fall into the sea; and then God, in his grace, restores them to their natural life.” It will thus be seen how intimate is the association between sailors and birds, particularly the kind of bird produced by rotten and sunken timber, and styled by the above very Early English naturalist “crabans,” or “cravans,” though “barnacles,” perhaps, is the term to best fit the prodigy. Even a dead bird may prove a soothsayer, according to Jack, for, says he, if a kingfisher be suspended to the mast by its beak it will swing its breast in the direction of the coming wind. Easier even than whistling for a breeze, and as a weathercock worth the lordliest and more flashing of ecclesiastical vanes, which will only tell how the wind is actually blowing. This is a vulgar error in Sir Thomas Browne’s list, but not exploded by that eloquent worthy. Nay, he rather explains it by remarking “that a kingfisher hanged by the bill showeth what quarter the wind is by an occult and secret property converting the breast to that part of the horizon from whence the wind doth blow. This is a received opinion, and very strange, introducing natural weathercocks and extending magnetical positions as far as animal natures—a conceit supported chiefly by present practice, yet not made out by reason nor experience.” But neither reason nor experience is desirable in superstition—that is to say if superstition is to flourish. It was long believed that gulls were never to be seen bleeding, and that the shooting stars were the half-digested food of these birds.[10] Why fancy should ever trouble itself with the blood of gulls is not clear; as to shooting stars it was reasonable that the method by which they were produced should be accurately stated and settled once for all. Some of the superstitions in connection with birds and their influence over things maritime are very curious and romantic. Anciently, swallows were deemed unlucky at sea, and we read that Cleopatra abandoned a voyage on observing a swallow at the masthead of the ship.

Footnote 9:

I advert to this singular article of marine superstition in another chapter.

“Swallows have built In Cleopatra’s sails their nests; the augurers Say they know not, they cannot tell, look grimly, And dare not speak their knowledge.”

Footnote 10:

Both the Rev. John Ray and Dr. Edward Browne (son of the famous Norwich Knight) speak of this queer belief in their “Travels.”

On the other hand, it was agreed that if a kite perched on a mast the omen was a favourable one. A crow lighting on a ship is accepted by the Chinese as a sure sign of prosperous gales, and they feed the bird with crumbs of bread by way of coaxing it to remain. The magpie is another evil bird. A sailor said to Sir Walter Scott, “All the world agrees that one magpie bodes ill-luck, two are not bad, but three are the very devil itself. I never saw three magpies but twice, and once I nearly lost my vessel, and afterwards I fell off my horse and was hurt.”

It is said that fishermen in the English Channel attribute the east wind to the flight of curlew on dark nights. It is possible that such a superstition may exist, nor could a far wilder fancy be held ill-founded by one who, in midnight darkness upon the sea-shore, has heard the dismal wailings and cryings of invisible birds speeding through the blackness in detachments, and making their weird noises sound as though they were uttered by one set of fowl wheeling round and round again. But, spite of Coleridge’s marvellous poem, the stately albatross, taking all the sea birds round, stands lowest in the catalogue of the feathered tribe, accredited with special necromancy in good or bad directions.[11] The little Mother Carey’s chicken, the stormy petrel, the tiny swallow of the deep, is distinctly ahead of the huge creature with its span of thirteen feet, and a score of superstitions crowd about it, such as its power of evoking storms, its being the soul of a dead sailor, and so forth. The albatross is beaten out of the field, too, by the common seagull, whose familiar presence is no doubt the cause of its rich legendary and traditional endowment. But for all that the albatross remains the sovereign of the seas, and unless the average duration of its life is already positively known, the discovery made in 1886 of the bird with the compass at its neck having been alive so long ago as 1848, will be received with interest by all admirers of the lovely and noble creature.[12]

Footnote 11:

“About this time a beautiful white bird, web-footed, and not unlike a dove in size and plumage, hovered over the masthead of the cutter, and, notwithstanding the pitching of the boat, frequently attempted to perch on it, and continued to flutter there till dark. Trifling as this circumstance may appear, it was considered by us all as a propitious omen.” This passage occurs in the account of the loss of the Lady Hobart in the Mariner’s Chronicle. What sort of bird this was, unless a gull, I cannot imagine.

Footnote 12:

An old legend states these birds to be the disembodied spirits of captains who have been wrecked off the Cape, and who are condemned to wear the feathers for seven years by order of the demon of the deep. An author writes fifty years ago: “Caught a splendid albatross; measured nineteen feet from the tip of each wing. He had been following the ship for many hours; but I was surprised to see what an insignificant figure he cut when dissected. He turned out all feathers.” He was no doubt a captain!

A boatman told me that once whilst fishing off the coast in forty feet of water, the tide a quarter ebb, and the sea a dark clear green, he and his mate were hanging over the boat’s side with lines in their hands when they saw a mermaid floating past under the surface by about the depth a man’s arm would penetrate. I asked him what the mermaid was like, and he replied that she was of a chocolate colour, with short black hair and very large intensely black eyes. Her figure to the waist was that of a woman; the rest of her was fish-shaped. Altogether he reckoned her to have been of the size of a thirty-pound salmon, only that she was longer than a fish of that weight would be. Her face and figure—as much of it as was human—were as small as those of a child two years old. She was an unmistakable mermaid—he’d warrant that. Might he never airn another shilling in this world if he wor telling a lie. She floated by at an oar’s length; had the sight of her left him and his mate their wits they would have secured her; but some minutes passed before they recovered from their amazement, and though they got their anchor and pulled in the direction of the creature they saw no more of her. I was glad to hear that there was, at all events, one mermaid still in existence, for I had been given to understand that the last of these ocean Mohicans had been gorged by the sea-serpent a little before the date on which her Majesty’s ship Bacchante sighted the Flying Dutchman.