Read and listen to the book Bomba the jungle boy : $b or, The old naturalist's secret by Rockwood, Roy.

Audiobook: Bomba the jungle boy : $b or, The old naturalist's secret by Rockwood, Roy

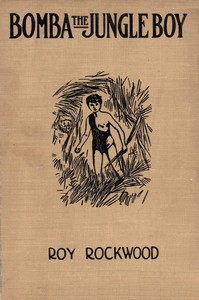

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Bomba the jungle boy, by Roy Rockwood

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: Bomba the jungle boy The old naturalist's secret

Author: Roy Rockwood

Illustrator: W. S. Rogers

Release Date: April 17, 2023 [eBook #70572]

Language: English

Produced by: Bob Taylor, David Edwards and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BOMBA THE JUNGLE BOY ***

Transcriber’s Note Italic text displayed as: italic

[Illustration: BOMBA BROUGHT THE PADDLE DOWN WITH ALL HIS FORCE.

“Bomba the Jungle Boy.” Page 71 ]

BOMBA THE JUNGLE BOY OR The Old Naturalist’s Secret

BY ROY ROCKWOOD

AUTHOR OF “BOMBA THE JUNGLE BOY AT THE MOVING MOUNTAIN,” “LOST ON THE MOON,” “THE CITY BEYOND THE CLOUDS,” ETC.

NEW YORK CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY PUBLISHERS

BOOKS FOR BOYS

By ROY ROCKWOOD

THE BOMBA BOOKS

12mo. Cloth. Illustrated.

BOMBA THE JUNGLE BOY BOMBA THE JUNGLE BOY AT THE MOVING MOUNTAIN BOMBA THE JUNGLE BOY AT THE GIANT CATARACT

GREAT MARVEL SERIES

THROUGH THE AIR TO THE NORTH POLE UNDER THE OCEAN TO THE SOUTH POLE FIVE THOUSAND MILES UNDERGROUND THROUGH SPACE TO MARS LOST ON THE MOON ON A TORN-AWAY WORLD THE CITY BEYOND THE CLOUDS

SPEEDWELL BOYS SERIES

THE SPEEDWELL BOYS ON MOTOR CYCLES THE SPEEDWELL BOYS AND THEIR RACING AUTO THE SPEEDWELL BOYS AND THEIR POWER LAUNCH THE SPEEDWELL BOYS IN A SUBMARINE THE SPEEDWELL BOYS AND THEIR ICE RACER

DAVE DASHAWAY SERIES

DAVE DASHAWAY, THE YOUNG AVIATOR DAVE DASHAWAY AND HIS HYDROPLANE DAVE DASHAWAY AND HIS GIANT AIRSHIP DAVE DASHAWAY AROUND THE WORLD DAVE DASHAWAY, AIR CHAMPION

CUPPLES & LEON CO., Publishers, New York

Copyright, 1926, by CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY

BOMBA THE JUNGLE BOY

Printed in U. S. A.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER PAGE

I A NARROW ESCAPE 1

II THE MEN WITH THE IRON STICK 9

III A STEALTHY FOE 17

IV HOW BOMBA SAVED THE CAMP 27

V BEATEN OFF 36

VI IN THE PUMA’S DEN 50

VII A SIEGE OF TERROR 59

VIII THE JAWS OF DEATH 68

IX FROM OUT THE FLAMES 77

X THE SHOUT OF WARNING 87

XI THE VAMPIRES ATTACK 97

XII KIKI, WOOWOO AND DOTO 105

XIII PLAYING FOR HIS LIFE 114

XIV THE CLOUD OF VULTURES 120

XV THE WRATH OF THE STORM 128

XVI GRIPPED 134

XVII IN THE FOLDS OF A BOA CONSTRICTOR 141

XVIII AT THE WATER HOLE 148

XIX A BATTLE ROYAL 153

XX AN UNEXPECTED RECEPTION 161

XXI BY A HAIR’S BREADTH 166

XXII THE TURN OF THE WHEEL 171

XXIII WORDS OF DOOM 180

XXIV AGAINST FEARFUL ODDS 189

XXV IN THE NICK OF TIME 198

CHAPTER I

A NARROW ESCAPE

Bomba came to a sudden halt in the densest part of the gigantic jungle.

A moment before he had been making his way with surprising suppleness and ease through the tangled brushwood, avoiding with equal dexterity the vines that trailed from the branches of the trees and the roots that reached out to trip him up. Now he stood as though turned to stone.

Far overhead the sun beat down fiercely from a brazen sky, though its rays were caught and held by the heavy foliage, so that beneath the branches of the trees semi-darkness prevailed. But if the brightness of the sun was thus excluded, its heat made itself felt, and masses of steaming vapor rose from the lush vegetation drenched by recent rains.

From a distance came the screams of parrots and the howling of monkeys, but otherwise the jungle was silent.

It had not been silent a moment before. From a point toward which Bomba was facing had come a sound that was new to the jungle and almost new to Bomba—a sound he had heard but twice. And each of those times was indelibly graven on his memory.

Once had been when Casson had brought down the savage jaguar with the iron stick or “rifle,” as Casson had called it. The beast had been crouching on the limb of a tree beneath which Bomba had sat down to rest. He had not seen the creature, whose huge body had been flattened close against the bough.

He had had no intimation of danger until he had seen the startled look in the eyes of Casson and heard his shout of warning. Then he had leaped to his feet. At the same instant the jaguar sprang. But Casson drew the iron stick to his shoulder, and a flame leaped from the end of it, accompanied by a sharp report.

The beast whirled about in mid-air and fell to the ground, one of its outstretched claws grazing Bomba’s leg as the latter sprang aside. The jaguar writhed and twisted about for a moment and then lay still.

When Bomba was sure the creature was dead, he had approached and examined it curiously. He had seen the natives kill game with arrows, and he half expected to see some missile protruding from the body. But there was no sign of this—only a tiny hole through the center of its forehead, from which blood was oozing.

He had questioned Casson curiously, but the latter was in one of his silent moods that day and gave no explanation. But the convulsive way in which he had strained Bomba to his breast told how deeply he had been stirred by the narrow escape.

The other time and the last that Bomba had witnessed the work of the iron stick had been when a giant anaconda had reared its horrid head in front of Bomba and darted forward to enclose him in its folds. Again Casson had fired, but this time instead of a loud crack there had been a thunderous roar, and the stick had exploded into a thousand fragments. Casson had fallen over on his back. The great snake, frightened by the noise and struck by some of the flying bits of iron, had hastily retreated. Bomba, who had escaped with some scratches, had managed to get the unconscious Casson back to the hut in which they dwelt, and there the old man had lain for many days, nursed by Bomba and treated with some of the simple remedies he had learned from the natives.

Casson had finally recovered, but had never again been the same. His head had been injured by the explosion, and his memory, which had been failing for some time, now almost wholly disappeared. At times he had flashes of recollection of his old life, but these were few and transient. Most of the time he was wrapped in moody silence, and Bomba felt more alone than ever.

But this had happened years ago, and the sound of the iron stick had almost passed from Bomba’s memory. Now he heard it again, and his pulses leaped.

It came from a distance perhaps half a mile away. Who had fired the stick? He knew that none of the natives had any weapon of the kind. Could it be some man like Casson, a man with a white skin like Casson’s and his own?

A white skin! Something tugged at Bomba’s heart. He could not have told what it was. It might have been memory, intuition, instinct. But whatever it was, it took instant and entire possession of him.

He must find out who had fired the iron stick!

The primal law of the jungle is to mind one’s own business. Intrusion on the affairs of another is never welcomed and usually resented. Bomba had learned to obey that law.

Ordinarily he would have given a wide berth to the locality from which the sound had come, swerved aside, and plunged deeper into the jungle. Where the iron stick sounded there was probably danger. It was associated in his mind with deadly beasts and reptiles. There was trouble enough in the jungle without looking for it.

Why, then, did he depart from all his usual caution and begin making his way toward the spot from which the sound had come?

He did not know. A confused tumult of thoughts and longings swept through his brain. He was conscious of a desperate urge that impelled him in that direction; and that urge came from the profoundest depths of his soul.

A white man must have fired that iron stick. The stick itself had some appeal to his curiosity. He would like to see it again—that mysterious thing that killed like magic from a distance.

But that desire was not compelling. Had he thought a native had fired it, he would not have risked intruding on what might be a hostile hunting party, possibly some of the dreaded head-hunters that occasionally invaded this region.

No, it was the craving to see a man with a white skin like his own, like Casson’s, that drew him on, drew him with a power he could no more resist than a chip could stem the current of Niagara.

To be sure, the white man might prove hostile. The deadly fire stick might be turned on himself. But he did not believe this. Casson had always been kind to him. All white men would be. Were they not his own kind? Was he not their brother? A wild surge of yearning swept over him.

All the longings he had felt so often, that came to him with increasing intensity day and night, that he had never been able to analyze and understand came to a head at the report of the iron stick. He could not resist them. He did not want to resist them.

He must see the man with the white skin!

Bomba was a striking figure as he worked his way through the jungle over sprawling roots and through a network of vines, gradually drawing closer to the spot from which the sound had come.

He was nothing more than a boy, fourteen years at most, of a little above the ordinary height at that age, compact and muscular. He had brown eyes and brown wavy hair and the whitest of teeth. His skin was darkly tanned by exposure to the sun.

On his feet were rude home-made sandals, and around his body was wrapped a bit of native cloth and a small puma-skin—the skin of Geluk, the puma, who had tried to eat the friendly parrots, Kiki and Woowoo. Bomba had caught him in the attempt and killed him with an arrow.

The skin heightened the resemblance of Bomba to a young panther as, light and supple, the muscles of arms and legs rippling under the bronzed skin, he threaded his way deftly through the underbrush.

Bomba lived with an old naturalist, Cody Casson, in the depths of the Amazonian jungle, so remote from civilization that it was rarely if ever visited by white men. Of his past he knew nothing, and so far Casson had told him next to nothing. He had given the boy some rudiments of education, especially in his own line of botany and natural history, but even this teaching had ceased years before when the old naturalist’s mind had been weakened by the exploding rifle.

Bomba knew nothing of the world at large, nothing of the white race to which he belonged, little even of the life of the natives of the region. For the pair did not mingle much with the latter and were themselves shunned by the superstitious natives, who had got the idea from the old naturalist’s queer actions that he was a Man of Evil.

Two eyes of which he was not aware were watching Bomba as he approached a narrow part of the rude native trail he was following, wicked eyes, malignant eyes glowing with lurid fires.

The eyes were set in the swaying head of a cooanaradi, the most terrible serpent on earth.

It lay in its lair just beside the path that Bomba was following, its body, fourteen feet in length, thrown into coils, above which the slender head swayed back and forth. Evilly beautiful, it glowed with all the colors of the rainbow.

Had it been a rattlesnake or any other poisonous denizen of the jungle, it would have glided away into the bushes, glad enough to avoid an encounter with human enemies unless attacked. Even the boa or the anaconda is apathetic and, except when moved by hunger, seldom takes the initiative.

But what makes the cooanaradi so dreaded, apart from its deadly poison, is its ferocity. It does not avoid attack; it seeks to make it. Nor is it satisfied when its enemy flees; it follows in pursuit.

But there was no need yet for that. All unsuspecting, its prey was coming toward it. Soon he would be in reach of the lightning stroke. The evil eyes gloated in anticipation.

Then, when Bomba was barely ten feet away, he saw it!

There was no time to string his arrow. There was no time to draw his machete. Even while he looked, the snake launched its spring.

Like a flash Bomba turned and ran for his life!

CHAPTER II

THE MEN WITH THE IRON STICK

At the moment that Bomba made his first startled leap he heard close behind him the thud of a body as it struck the earth. The reptile had missed its spring.

But this brought Bomba small comfort. He knew that the fight had just begun, that behind him death was coming and traveling fast.

One look was all he cast behind him, but that was sufficient to show the slithering long body of his implacable foe moving swiftly along the trail.

Bomba was agile and fleet of foot, and he tore along at an astounding rate of speed. But he knew too much of his adversary to believe that he could distance it. In the long run, the endurance of the snake would outlast that of the fugitive.

But if Bomba’s feet were fast, so was his brain, and it was working now with lightning rapidity. It was recalling every turn and oddity of the trail along which he was speeding.

There were plenty of trees, but before he could get a grip and begin to climb, the fearful thing would be upon him. And even if he had sufficient start to avoid the first stroke, the snake could climb much more rapidly than Bomba could dream of doing.

Had there been a stream at hand, he would have plunged into it, although he might have become the prey of some lurking cayman or been torn to bits by the fierce piranhas. Either of those fates would have been a possibility. But he would at least have had a chance of not being attacked, while, unless he could escape from the cooanaradi, death was a certainty.

At times, when he came to a little opening, he would dart off to the right or the left, so as to disconcert the enemy. This had the desired effect more than once, and enabled him to get some space ahead before the snake was again at full speed on his trail.

Bomba’s breath was fast failing him, but his courage and mental alertness still remained. Then he caught sight of something that gave him a gleam of hope.

It was a thick, matted mass of whiplike streamers hanging from one of the trees. It spread out like a huge fan with narrow interstices between the tough withes. Behind this screen he darted like a flash and stood there panting, facing the enemy.

The cooanaradi was not twenty feet away, coming at tremendous speed, its eyes red with fury. As it approached, Bomba thrust his face against the screen and shouted.

What he had hoped came to pass. The snake, infuriated at the challenge, reared and struck at the face of his foe. Bomba dodged, and the opened jaws of the snake caught and in turn were held by the matted mass into which the fangs had sunk.

It writhed wildly and tried to extricate itself. But in an instant Bomba had leaped to the other side of the screen. His hands worked like lightning, deftly winding the withes like cords around the twisting body, until it was securely enmeshed in a net from which there was no escape.

Only when he had made sure of his victory did Bomba desist and stand panting a little distance off, watching the unavailing efforts of the captive to free itself.

Craft and cunning had triumphed over the fiend of the jungle. The boy had had a narrow escape from one of the most terrible of deaths, and he owed it solely to his own speedy feet and active brain.

He was drenched with perspiration from head to foot. His lungs were strained almost to bursting. His breath came in great gasping sobs. But he had won, and every nerve tingled with exultation.

His hand slid to the handle of his machete, a formidable double-edged knife ground to almost a razor’s sharpness and fully a foot in length.

But after a moment’s reflection he slipped the partly drawn weapon back in his belt. A slash at the snake might sever some of the withes with which it was bound, only wound the reptile and permit it to get free.

No, the jungle itself could be trusted to finish the work begun by the boy. The peccaries, or wild pigs, would happen along, and to them a snake was the daintiest of foods.

Or there were the vultures. Bomba cast his eyes upward through an opening in the trees and saw one of these rapacious creatures circling about and slowly descending, already attracted by that almost miraculous instinct that tells the carrion eaters where death has come or is imminent.

And even the vulture would have to come soon, or a swarm of ants would be going over the reptile stripping the flesh from the bones.

In the excitement of the flight and pursuit, Bomba had forgotten for the moment the object of his quest. Now it came back to him with the force of a shock.

The white man with the iron stick! Could he find him now? Or was he too late?

He cast one glance at his captive to make sure that it was securely held. Then having satisfied himself on this point, hurriedly resumed his journey.

But he did not follow the same path on which he had found the cooanaradi. He knew that these reptiles usually traveled in pairs, and he had no desire to encounter the mate of the one that had so nearly proved his doom.

So he made a wide detour, although he bitterly resented the necessity of doing so, for now a fear that was almost panic assailed him that he might miss meeting the man with the iron stick. It was already late in the afternoon, and unless he came upon him before darkness set in, he would probably fail altogether in finding him. And this possibility had by this time assumed the proportions of a calamity.

Why he should lay such stress on this was more than Bomba could explain, even to himself. But the fact was there. He must find this man!

There was no trail in the direction he had been forced to choose, and often he had to hack his way through the underbrush with his machete. It was laborious and exhausting work, and it was nearly an hour before he caught a scent of roasting meat that told him he was in the vicinity of some human inhabitant of the wilds.

Now he worked with extreme caution, for he was by no means sure of his reception, and he wanted, from the safe seclusion of the jungle, to form his own ideas of conditions before venturing into the open.

A few minutes more of stealthy approach, and he heard the sound of voices. Some of these he recognized at once as those of natives.

But there were other tongues too, and with a thrill he realized that they were speaking the same language that he and Casson used and that he had never yet heard from other lips! Some of the words he could not understand, but the simpler ones were familiar.

He tingled with delight. He was not then too late. The white man was there. He could look upon him, devour him with his avid eyes, perhaps speak with him!

A moment later he reached the fringe of the heavier jungle. Beyond, it widened out into a glade of considerable extent.

He dropped on his knees and wormed his way to a great tree near the edge. Then, lying flat on the ground, he carefully parted the underbrush and peered through.

He saw at once that he had come upon a considerable party. A rude tent had been pitched in the center of the glade, a number of packs littered the ground, and a dozen natives were engaged at various tasks. A fire had been built, and some freshly cut steaks of meat, stuck on spits, were being roasted by native cooks.

Bomba gave these but a cursory glance. His eyes were riveted on two men, one tall and gaunt, the other stocky and muscular, who sat on adjoining stumps conversing with each other. One was cleaning and oiling an iron stick. The other was skinning the body of an animal the size of a calf that Bomba recognized from its coarse hair and blackish brown hide as that of a tapir, whose life had evidently been taken by the shot that Bomba had heard.

The faces of the men were bronzed, but their shirts were open at the throat, and Bomba could see the white skin like his own and Casson’s.

Again that strange thrill shot through him and he had all he could do to repress a shout of delight.

He scanned their faces closely. They were keen faces, alight with intelligence. How different, Bomba thought, from the vacuous faces of the natives who surrounded them. To him they seemed like visitants from another sphere.

And they were kindly faces. The men were laughing and joking with each other, evidently in the best of spirits. There was nothing there that need arouse fear in any but evil-doers. His heart warmed with a sense of kinship.

Impulsively he rose to go out into the clearing. Then he sank down again. Shyness, reticence, caution, the restraint bred of the jungle! He longed to show himself, yet he shrank back.

His problem was solved for him. His sudden movement had caught the keen eye of a native. Instantly the fellow shrilled an alarm.

The white men snatched their iron sticks and sprang to their feet.

The die was cast! Bomba leaped out into the open!

CHAPTER III

A STEALTHY FOE

An exclamation of surprise came from the white men as Bomba advanced toward them with his upraised palms, extended as a sign of amity, and they lowered their rifles.

“Just an Indian kid!” remarked the stockier of the two with a laugh.

“Indian nothing!” retorted the other, as his keen eyes swept the lad. “Look at his hair, his eyes, his features. He’s as white as we are, or my name isn’t Gillis. Look again, Dorn.”

“Guess you’re right, old man,” conceded Jake Dorn, after a close scrutiny. “But what in the mischief is he doing here? I didn’t know there were any other whites within a thousand miles of us.”

“Neither did I,” replied Ralph Gillis. “But we were evidently wrong. Probably he belongs to some other camp of rubber hunters not far away.”

“But look at his clothes, if you can call them clothes,” said Dorn, with a puzzled air. “I never saw a white boy dressed like that. Nothing but a clout and a puma skin.”

“We’ll soon solve the mystery,” said Gillis. “Come here, boy,” he added kindly.

Bomba came shyly toward him.

“What is your name?” asked Gillis.

“Bomba,” was the reply.

“Bomba!” repeated Gillis, with a frown of perplexity. “That’s a queer name for a white boy. For you are white, aren’t you?”

“Yes,” replied Bomba proudly, as he drew aside the puma skin and exhibited his chest.

“And since you understand what I say to you, you must be either American or English,” pursued Gillis. “What is your other name?”

“I haven’t any,” was the reply. “I am Bomba.”

The men exchanged puzzled glances.

“Who are your folks?” put in Dorn.

Bomba pondered for a moment.

“I don’t know what that word means,” he replied simply.

“Well, I’ll be jiggered!” exclaimed Gillis. “I mean your father, your mother.”

“I guess I never had any,” replied Bomba. “I never saw them or heard of them.”

“The poor kid!” murmured Dorn.

“But you must have somebody to live with or take care of you,” said Gillis.

“Yes,” replied Bomba, “I live with Cody Casson.”

“Who is he and where is he?” asked Gillis.

“He is an old man,” answered Bomba. “He lives in a hut a long way off,” and he pointed toward the south.

“Is he a relation of yours?” asked Dorn.

“I don’t know what that means,” was the answer.

Gillis threw up his hands in despair.

“Well, wouldn’t that get your goat?” he ejaculated.

“I haven’t got any goat,” replied Bomba, who thought the question was addressed to him.

The men laughed heartily, and Bomba, though a little puzzled, laughed with them. He was glad that he had said something that pleased them. They were nice men. His heart warmed to them.

Gillis returned to the attack.

“When did you come into this jungle?” he asked.

“I have always been here,” answered Bomba.

“But don’t you remember ever living anywhere else?” persisted Gillis. “Don’t you remember coming over the ocean?”

“What is the ocean?” asked Bomba.

“It is like a river, but a thousand times as big,” explained his questioner.

Bomba shook his head.

“No,” he said. “I never saw any water I could not swim across.”

“Haven’t you ever heard of England or America?” put in Dorn.

“No,” was the reply. “There are no animals here that have those names.”

A glance of pity passed between the two men.

“An untutored child of nature, if there ever was one!” exclaimed Gillis. “How in heaven’s name do you explain it?”

“Search me!” replied Dorn. “Seems to me the only thing to do is to hunt up this fellow Casson and get it out of him. The boy ought to be taken out to civilization and have his chance.”

“He ought,” assented Gillis. “Though I don’t see how we can do anything just now, for our road lies in the opposite direction and we’re behind our schedule now. We’ve got to get to the coast in time to get that steamer. But later on we’ll take the matter up ourselves or have some of the authorities look into it. But those steaks are done now, and I’m as hungry as a wolf. This young visitor of ours shall fill up too, if he cares to stop and eat with us.”

Bomba gladly accepted the invitation, not only because he was hungry but because it gave him a chance to stay in the company of the white men. He would have liked to stay with them forever. The thought of parting filled him with dread.

They brought knives and forks from their kit and offered one of each to Bomba. But he did not know their use, had never seen them, and ate his meat by plucking it apart with his teeth and fingers, as was his custom, the while he watched with wonder the deft way in which the table utensils were used by his new acquaintances.

He felt that it must be a better way than his. The white men did it, and he himself was white and ought to do it too. Before he was half way through the meal, he shyly reached out for the knife and fork and tried to imitate them. The effort was not very successful, but they sensed his feeling, and be it said to their credit they did not laugh.

The meal was interspersed with questionings, in the course of which the men learned much and gained marked respect for Bomba’s courage and self-reliance. They were aghast at his story of the way he had trapped the cooanaradi, and would not have believed it had not the simple way that Bomba told it carried conviction. He did not boast, merely narrated the incident as though it were not of any particular importance and simply a part of the day’s work in the jungle.

“Why not take the boy along with us, if he’s willing?” suggested Gillis, thoughtfully, to his companion. “It would bring him out to civilization, and at the same time he’d be a mighty valuable addition to our party. We’d be killing two birds with one stone.”

“Right enough,” agreed Dorn. “How would you like to go along with us?” he asked, addressing himself to Bomba.

The boy’s heart leaped and delight shone in his eyes. Oh, how he wanted to go! But the next moment the light faded and his heart sank.

“I could not leave Casson,” he said. “He would die if I left him alone.”

“The boy’s true blue,” said Gillis, “and we mustn’t tempt him. But soon or late we’ll see this Casson and perhaps get them both out of the jungle. The whole thing is the queerest affair I ever came across.”

He struck a match to light his pipe, and Bomba jumped at the sudden spurt of flame.

“Never see one of those before?” asked Dorn, in surprise.

“No,” replied Bomba. “I make fire like this.”

He took a stick and a tiny wooden bowl from his belt, twirled the stick dexterously, and in a few moments produced a spark.

“Well done!” cried Dorn admiringly.

Bomba was pleased at the note of approbation, but in his heart he knew that the white men’s way was quicker and better. He looked longingly at the matches, and Gillis, with a smile, handed him a box of them, which Bomba grasped eagerly and thrust into the small pouch at his belt. Now he could make fire as the white men did. He felt that he was growing closer to them.

Gillis showed him his rifle. It was a far finer iron stick than Casson’s had been, and Bomba examined it with the greatest curiosity.

He did not in the least understand the principle of it, but he knew its power. The dead tapir was evidence of it, as well as his memory of the way a similar stick had slain the jaguar.

“I’ll show you how it works,” volunteered Gillis, noting the boy’s eager interest in the weapon.

Bomba nodded delightedly. This was what he had been wishing for ever since he had reached the camp, but had been too shy to ask of his own accord.

Ralph Gillis took a card and tacked it up against a tree about fifty feet away, Bomba watching him intently.

Then Gillis took up his position and raised the rifle to his shoulder. Bomba, with a lively recollection of what had happened when Casson had fired at the anaconda, edged some distance away.

There was a sharp crack, and Bomba’s keen eyes noticed a slight quivering of the card.

“Come along,” said Gillis, beckoning to the boy, and Bomba followed him to the tree, where he saw a small hole in the card that had not been there before. But he looked in vain for any sign of scorching.

“Why didn’t the fire burn it?” he asked.

Gillis looked at him perplexedly, and then laughed as he grasped his meaning.

“Bless you,” he said, “it wasn’t the fire you saw coming from the muzzle that struck the card. It was a cartridge just like this,” and he drew one of the pellets from his belt.

Bomba examined it curiously.

“Why didn’t I see this when you fired the iron stick?” he asked.

“It went too fast for you to see,” explained Gillis patiently.

“You could see my arrow if I shot it,” said Bomba.

“That’s different,” said Gillis. “The arrow is bigger, and it doesn’t go as fast. And it doesn’t go as straight, either.”

“It goes straight,” declared Bomba.

“Do you mean to say that you could hit that card?” asked Dorn incredulously.

“Yes,” said Bomba.

“I’m from Missouri,” remarked Gillis.

“Where is that?” asked Bomba.

The men laughed.

“Never mind,” said Gillis. “Let’s see you hit the card.”

Bomba drew an arrow from his belt, fitted it to the string, and, scarcely appearing to take aim, let it go.

A cry of surprise broke from his new acquaintances as they saw the arrow standing out straight from the center of the card.

“The boy’s a wonder!” cried Gillis.

“Robin Hood had nothing on him!” declared Dorn.

“Who was he?” asked Bomba. “And why did he have nothing on him?” as he glanced at the well-clothed forms of the white men.

“I can see that we’ll have to cut out slang,” laughed Dorn. “Robin Hood was a great shot with the bow and arrow, and what I meant to say was that you could shoot as straight as he could.”

Bomba’s heart swelled with pride at the approbation of the white men. It seemed to him the sweetest music he had ever heard.

Dusk was drawing on now, and the forest began to waken. From the lairs in which they had lain during the heat of the day wild beasts rose, yawned, stretched themselves, and then stalked out on their nocturnal search for prey. Death was abroad.

Two or three times, as Bomba sat by the tent of his new-made friends, he raised his head and sniffed the air.

“What is it?” asked Gillis curiously, after the third repetition.

“Jaguars,” answered Bomba.

The men grasped their rifles and peered into the darkening forest surrounding them.

“I don’t see any,” remarked Gillis, after a moment.

“They see you,” replied Bomba.

The calm matter-of-fact statement sent a little chill down their spines.

“How do you know there are any about?” asked Dorn.

“I smell them,” was the reply.

“On what side of the camp are they?” queried Gillis.

“All sides,” said Bomba.

CHAPTER IV

HOW BOMBA SAVED THE CAMP

The men sprang to their feet at this ominous declaration and their eyes swept the forest in every direction.

“And the boy speaks of this as calmly as though it meant nothing to him or us!” exclaimed Jake Dorn.

“I wonder if he really knows what he is talking about,” cried Gillis. “Tell me,” he demanded turning to Bomba, “what makes you think there are jaguars all about us?”

“I smell them and I hear them,” returned Bomba. “First I heard them a long way off. They were screaming. Then they came nearer, and they were snarling. Now they are nearer still, and they are purring. I hear them.”

“More than I do, then,” said Gillis, after a few moments, when he and his comrade had listened with all their ears. “But I’ve heard some wonderful stories of the smell and hearing of those who have lived long in the jungle, and perhaps the boy is right. If he is, we’ve got a fight on our hands all right. When is this little shindig going to take place?” he asked Bomba grimly, as his hand tightened on the stock of his rifle.

“I do not know shindig,” answered Bomba.

“When will the jaguars try to kill us?” asked Dorn.

“Not for a long while,” replied Bomba. “Not till it gets very dark and many more come.”

“That’s cheerful,” muttered Gillis.

“They smell the blood of the tapir,” Bomba went on. “Then they come and see many men here. Much meat for the jaguars.”

“We’ll leave out those pleasant little details,” said Dorn, repressing a shudder. “It seems likely that we’re in for the fight of our lives, and you and I will have to do the most of the fighting, Gillis. These natives aren’t good for anything.”

“I will help,” said Bomba.

“By ginger, I believe the boy will!” exclaimed Gillis. “He’s as plucky as a wildcat. Though I’m afraid that bow and arrow won’t do much against such beasts.”

“I have my machete,” Bomba reminded them, half drawing the gleaming weapon from its leather sheath.

“I’m blest if the little rascal isn’t thinking of fighting them hand to hand!” ejaculated Gillis in admiration.

“I do not want to, but I will if I have to,” said Bomba. “It is better to kill than be killed. But wait, I think of something.”

While he had been talking, his eyes had been roving among the trees that edged the clearing, and they lighted as they fell on a tree with triangular pointed leaves.

He pointed to a pail that was lying near one of the packs.

“Let me have that,” he said, pointing to it.

“What do you want of it?” asked Dorn.

“Don’t bother with questions,” suggested Gillis. “The boy has something in mind, and after what I’ve seen of him I’m willing to give him a free hand. Here it is,” handing the pail to him.

“Now,” said Bomba, “make the fire big. The jaguars will go back from the light. I have to go into the woods. I do not want them so near.”

Gillis gave a few sharp orders to the natives and they heaped brush on the fire, which had been allowed to die down, and soon it was crackling fiercely, sending a broader zone of light through the surrounding forest.

This made the immediate proximity safe for the time, and Bomba took the pail and started out for the tree he had discerned.

“Wouldn’t one or both of us better go with you?” asked Dorn anxiously. “It isn’t right to let you go in there alone.”

“No,” said Bomba. “I must do my work myself. You can keep the iron sticks ready. But you will not need them yet.”

He took the pail and went unhesitatingly into the woods. The heavy underbrush closed behind him and swallowed him up, though the lurid glare of the fire gave those in the camp occasional glimpses of his progress.

Bomba made his way toward the tree he sought, and, reaching it, set down the pail and drew his machete.

He drove the knife through the bark and into the body of the tree as far as his strength permitted. Then he drew the knife down in a long vertical slash.

He pulled the blade out, lifted the pail, held it under the cut and waited.

In a few moments a sticky sap began to exude from the tree, at first slowly, and then more rapidly. Soon it was trickling in a thin stream into the pail.

It was eerie work waiting there, where he knew that greenish-yellow eyes were watching him from the jungle, only deterred for the moment from coming nearer by the light that came from the fire. But Bomba had learned patience in the hard school of the jungle, and he stood like a statue, the pail in one hand, his machete in the other ready for instant use, until the receptacle was nearly full.

Then he took it and, tilting it slightly so that a thin but steady stream fell on the leaves that carpeted the jungle, he made the circuit of the camp.

The white rubber hunters caught sight of him at intervals during his course, and watched his progress with bated breath.

“What on earth do you suppose the boy is doing?” asked Dorn.

“Looks as though he were weaving some magic charm out there,” muttered Gillis. “Something perhaps that he has learned from the witch doctors of the region. It’s making me creepy! It’s uncanny!”

The men were immensely relieved when Bomba at last emerged from the shadows, put down his empty pail, and seated himself on a stump near them.

“What have you been doing?” asked Gillis.

Bomba picked up the pail.

“Feel,” he said, pointing to the interior.

Gillis put his finger on the bottom of the pail, and when he withdrew it, it was covered with a pale, yellow, sticky substance. It felt uncomfortable, and he tried to rub it off with a bit of cloth. But this he found was almost impossible.

“Sticks closer than a brother,” he muttered. “What is it and where did you get it?”

“From the tree,” replied Bomba. “I stuck my knife in the tree and hurt it. The tree wept. These are the tears of the tree.”

“By Jove!” exclaimed Dorn, “the boy’s a poet.”

“Right enough,” agreed Gillis. “What he means, of course, is that he tapped the tree and got this gum-like sap from it. But why did you do it and what have you done with most of the sap?” he asked, addressing himself to Bomba.

“I spilled it on the leaves all around the camp,” said Bomba. “It is good for us and bad for the jaguars.”

The men looked at each other in perplexity.

“Can you make out what he’s getting at?” asked Dorn of his companion.

“Not in the least,” replied Gillis. “It’s all Greek to me. How is it bad for the jaguars?” he asked Bomba.

“The jaguars step on it,” explained Bomba. “The leaves stick to their feet. They try to shake them off. But the leaves stick. Then they try to rub them off with their heads. The leaves stick to their heads. The gum gets in their eyes. It is bitter. It makes them blind. They get frightened. They cannot see where they are going. They forget all about the white man and the meat. They cry. They run. That is all.”

The men looked at each other, struck dumb with amazement.

“That is all!” exclaimed Gillis, when he had recovered his breath. “By ginger, it’s enough!”

“I should say it was,” agreed Dorn. “Boy, I take off my hat to you.”

As he was bareheaded at the moment, Bomba was a little puzzled at this, but he sensed the warm approval of the white men, and his heart rejoiced. He, too, was white, and he had made his brothers happy.

He thought it well, however, to add a word of warning.

“You must keep the iron sticks ready,” he said. “Most of the jaguars will be stopped by the gum. But some of them, maybe one, two, three, will miss the leaves that stick and they will get into the camp.”

“We can probably handle them,” said Gillis. “At any rate we’ll do our best. I only wish we had more brushwood to keep the fire going strong. But we hadn’t counted on this wholesale raid, and now it would be as much as one’s life was worth to go into the forest for more. We’ll have to worry along as best we can.”

Having to husband their resources, they could only maintain a moderate fire, and as the hours wore on they had to be still more economical in feeding it.

As the zone of light narrowed they knew that their enemies were creeping closer, waiting only for the most opportune moment of attack.

They had put the camp into the best position for defense that circumstances permitted. The natives had been warned of the danger and had spears and arrows ready, though the white men knew that they would be far more ready to run than fight when the pinch came.

Toward midnight a sudden spitting and snarling rose on one side of the camp, to be taken up shortly on the other. There came the sound of heavy bodies rolling about in the underbrush and crashing through thickets. All the natural caution of the cat tribe seemed to have been abandoned in a rush of panic terror. The snarls and roars swelled into a hideous din that made the natives quake with fear, but that the white men understood.

Bomba’s spell was working!

But though they exulted, they did not abate one jot of their vigilance.

It was fortunate for them that they did not, for a few minutes later a huge, tawny body came hurtling through the air, landed within twenty feet of Gillis, and crouched for a second spring.

Two rifles spoke simultaneously with the twang of Bomba’s bow. The jaguar quivered, rolled over on its side, and lay still.

While their eyes were still fastened on it there came a roar from another direction, and a second jaguar landed behind Gillis and Dorn. They turned and fired, but so hurriedly that they either missed or only slightly wounded the animal. Before they could fire again it would be upon them! They dodged and clubbed their rifles, horror-stricken, awaiting the attack.

Like a flash Bomba drew his machete.

The beast launched itself in the air.

CHAPTER V

BEATEN OFF

Through the air whizzed a gleaming, long, razor-edged knife that buried itself in the jaguar’s throat!

The stricken jaguar landed on the spot where but a moment before, Gillis and Dorn had stood, and sprawled out in a heap. It made one or two frantic digs at its throat in the attempt to dislodge the machete. But it had gone deep and the beast’s efforts were unavailing. A few convulsive struggles, and it was dead.

Amazed at this sudden end of their foe, the men approached it cautiously and prodded it with the butts of their guns. But there was no movement. The knife had done its work effectively.

Dorn’s eyes caught sight of the handle of the weapon, and he stooped down and drew it out, though he had to tug hard to get it. He held it up before his astonished companion.

“How did this get there?” asked Gillis.

“It is mine,” said Bomba, coming up and reaching out his hand to reclaim it.

“Yours?” demanded Dorn. “Why, you weren’t near enough to stab the beast!”

“I threw it,” said Bomba, wiping the knife on the grass and slipping it back into his belt.

“G—great Scott!” stuttered Dorn. “He—he threw it!”

“And threw it as straight as he shot the arrow!” ejaculated Gillis. “And with so much force that you had all that you could do to draw it out. Boy, you’re a wonder! You saved the life of one or both of us!”

“I was glad to help you,” said Bomba, showing all his white teeth in a happy smile. “But now we must put the jaguars near the edge of the woods where the others will see them.”

“What’s the idea?” queried Gillis. “So that they can’t feast on them and not be so hungry after us?”

“No,” said Bomba. “The others will not eat them. They fight and kill each other when they are angry, but they do not eat one another. But when the live ones see these dead ones, they will know that this place is not good for jaguars, and they will go away.”

“Sounds reasonable,” said Gillis. “But whether the plan works or not, what this boy says goes. I’m frank to confess that he’s got me buffaloed. If he hadn’t been here to-night, you and I would have been dead men, Dorn.”

“He’s saved the camp all right,” assented Dorn, as he directed some of the natives to drag the heavy bodies to the places that Bomba indicated.

That the sight of their dead kindred daunted whatever other jaguars might have intended to make an onslaught on the camp, seemed clear as time went on. The jungle was vocal, as it always is at night, with the strident notes of insects, the howling of monkeys, and now and then the distant bellow of an anaconda.

But the jaguars seemed to have taken themselves off. Bomba’s keen ears could no longer detect the subdued growling and purring of the four-footed raiders, the soft thud of their padding feet. Nor were his nostrils conscious of their presence.

After a full hour had passed, he relaxed his tense attitude, stretched, and yawned.

“They have gone,” he announced.

“Are you sure?” asked Gillis, eagerly.

“They have gone,” repeated Bomba. “And they will tell the others. They will not come back. I will sleep.”

“Go to it, my boy,” said Dorn. “You’ve earned it, if ever anyone did. I don’t know what we’d have done without you.”

“Our name would have been Dennis,” declared Gillis.

“I thought your name was Gillis,” said Bomba wonderingly.

“It is,” was the laughing reply. “I keep forgetting that you don’t know our slang. I mean our name would have been mud—there I go again. What I mean to say is that we would have been killed if you had not been here.”

Bomba made up his mind that he would remember these new words so that he could talk like the white men. He already had a precious collection, “goat,” “mud,” “Dennis,” “shindig.” And there had been others, too, that he would try to recall. He would tell them to Casson and show him how much he had learned. But just now he was very sleepy.

“I’ll get you some blankets to lie on,” said Gillis.

“No,” said Bomba, “I will sleep this way.”

He threw himself down on the ground near the fire, and in a moment was fast asleep.

But there was no sleep just then for Gillis or Dorn. They were too wrought up by the dreadful experiences through which they had gone to close their eyes. So they sat with their rifles on their knees until the first faint tinge of dawn showed in the east. Then they knew that the danger was past, for that night at least, and after summoning a couple of natives and placing them on watch, they threw themselves wearily on their blankets in a sleep of utter exhaustion.

Bomba was the first to awake, and for a moment found it hard to realize where he was. He sat up, looked around, and caught sight of the bodies of the jaguars. Then all the events of the stirring night came back to him.

He had borne himself well in circumstances that might have made grown men quail. He had met death face to face, and it had been a matter of touch and go whether he would escape unscathed. But the fortune that favors the brave had been with him, and he had not a scratch. He had trapped the cooanaradi. He had slain one jaguar and foiled the others. It was natural that he should be filled with a feeling of exultation.

But far above the satisfaction at his own safety was that which came from the thought that he had saved the white men. Without him, they would surely have been doomed! He had established his right to be regarded as a brother. He had vindicated his white skin.

In twenty-four hours he had gone far. A new world had opened before him. He had crossed a chasm that separated him from his own race. He had realized some of the dreams, answered some of the questions, solved some of the mysteries that for a long time past had been tormenting him.

But he realized that he still had far to go. How much these white men knew! In what a different world they moved! How far superior they seemed to him! How ignorant he was, compared to them!

But he would learn. He would ask Casson. Casson must know all the things the other white men knew. And then his heart sank, as he realized that Casson seemed to have forgotten all or almost all that he had ever known. There was little help to be expected from the man with whom Bomba lived.

He was engrossed in these meditations when Gillis opened his eyes. They fell on Bomba, and recollection came into them.

“How does our hero feel this morning?” asked Gillis, with a genial smile.

“What is a hero?” asked Bomba, with his usual directness.

“Why, you fill the bill as well as anyone I ever saw,” returned Gillis. “A hero is a man or boy who isn’t afraid.”

“But I was afraid last night,” said Bomba.

“I guess we all were,” remarked Gillis. “Well then, a hero is one who, even if he is afraid, doesn’t let fear get the best of him, but fights on and makes up his mind to keep on fighting till he dies. And that’s what you’d have done last night if it had come to that. But it’s getting pretty late, and we’ll have to get a move on.”

He shook Dorn awake, gave some orders to the natives, and soon the camp was alive with preparations for breakfast.

This time Bomba took his knife and fork at the outset, and was gratified to note that he could already handle them much better than he had on the night before.

“Well, now, my boy,” said Gillis, after they had enjoyed a hearty meal, “we’ll have to be packing and getting on our way. As we told you last night, we’d like nothing better than to have you go along with us. Still think you can’t, eh?”

“I should like to go,” replied Bomba, and the look in his eyes was much more eloquent than words. “But Casson is old and sick. He has been good to me. I have to get his food for him. He would die if I should go.”

“That settles it then, of course,” said Gillis regretfully. “But don’t you think, my boy, that we’re going to forget you. We owe you too much for that. Either we’ll come back, or we’ll send someone else to get you and Casson out of this jungle and bring you where you belong. In the meantime, we want to do something to show you how grateful we are. You saved our lives, and we want to do something for you.”

“You do not have to give me anything,” said Bomba, simply. “I was glad to help you.”

“All the same, you’ll have to take something,” put in Dorn. “The question is, what shall it be? The boy can get all the food he wants, and I don’t suppose he has any use for money.”

“What is money?” asked Bomba.

“About the most important thing in the world outside this jungle,” said Gillis. “This is money,” and he took a gold piece from his pouch and spun it on the rude board that served as a table.

“It is pretty,” said Bomba.

“A good many people think so,” remarked Gillis, dryly. “Some would sell their soul for it.”

“What is a soul?” asked Bomba.

“You’re getting in deep, Gillis,” laughed Dorn.

“I sure am with this animated interrogation mark,” returned his comrade. “The soul is the best part of us, the part that makes men good and wise and brave, that makes them different from the animals.”

“Have I got a soul then?” asked Bomba.

“You sure have,” replied Gillis. “And one of the best, if you ask me. But we’re getting off the subject. We want to give you something that you would like to have. I wonder what it would be.”

His eyes roved about and caught sight of a harmonica that lay in one of the packs they had brought along for trading with the natives.

“How would you like this?” he asked of Bomba, as he picked it up and handed it to him.

Bomba examined it curiously. He liked its smoothness and its glitter.

“What is it?” he asked.

“Let me show you,” said Gillis, as he took it from him, put it to his mouth, and played a few bars of a popular air.

Bomba was amazed and delighted.

“It is like a bird!” he exclaimed. “It sings!”

“Try it yourself,” said Gillis, handing it over. “Blow your breath into it and draw your breath back.”

Bomba did so, and although the notes he brought from it were meaningless and discordant, they thrilled him with rapture. He could make music like the white men.

“Keep it,” said Gillis, highly pleased at the lad’s delight. “It’s yours.”

“It is good to give me this,” said Bomba gratefully, as he fondled his treasure. It was the first present he had ever had in his life.

“We’d feel cheap enough if we let it go at that,” said Dorn. “How about giving the boy a revolver? You saw how curious he was about firearms.”

“Right enough,” assented Gillis, as he went into the tent and returned with a shining new five-chambered revolver. “Here, Bomba, you liked the big iron stick. This is a little iron stick, but it does very much the same thing as the big one.”

“Oh, are you going to give me that?” exclaimed Bomba, scarcely able to believe his eyes.

“Sure thing,” said Gillis. “Here, let me show you how it works.”

He broke the revolver, and Bomba gave a gasp of dismay.

“You broke it!” he exclaimed in grief.

“That’s all right,” replied Gillis. “I have to do that to load it. See, this is the way it is done.”

He put cartridges in the five chambers, while Bomba watched him breathlessly. Then he snapped the stock back and looked around for a mark.

One of the dead jaguars caught his eye, and he emptied the revolver into the carcass, firing so rapidly that it seemed almost one continuous explosion.

“Now go take a look at the jaguar,” said Gillis. “You’ll find five holes that weren’t in it before.”

Bomba confirmed this with his eyes. It still seemed to him like magic, and there was awe mingled with delight in his ownership of the weapon.

“Let me put five more holes in the jaguar,” he begged.

Gillis loaded it for him and gave him directions how to hold, aim, and fire the weapon, though he and Dorn took care to take their stand behind him.

In the tyro’s hands only one more perforation marked the jaguar’s hide, the rest missing the mark through Bomba’s unfamiliarity with the weapon and his failure to allow for its kick.

“All right for a beginner,” commented Gillis. “With your natural keenness of eye you’ll be a crack shot as soon as you get used to the gun and have a little more practice. I only wish we had more time to teach you. But Casson will give you lessons, and in a little while you can shoot as straight with this as you can with your bow.”

Many boxes of cartridges accompanied the gift, and Bomba tucked them away carefully in his pouch, feeling as rich as Croesus. It had certainly been a lucky day for him when he had come across the white men!

But his delight in his treasure was dimmed when, a little while later, all preparations were completed and the party got ready to move.

The rubber hunters themselves, steeled adventurers as they were, were deeply stirred as they shook hands with Bomba and bade him good-bye. They had become strongly attached to this lad, who had come upon them so strangely, and to whom, no doubt, they owed their lives. There was tragic pathos in his loneliness in these vast wilds with only a half-demented old man to bear him company.

“You’ll hear from us again, remember that,” promised Gillis. “We’re not going to let this thing drop. We will come back or send back for you.”

“I hope so,” said Bomba. “If you do not come, my name will be mud.”

The men could not help smiling, and Bomba was proud. He was showing them that he could talk like the white men.

They waved a final farewell and took up their journey through the jungle. Bomba watched them until the underbrush hid them from view.

The world suddenly became very empty. His eyes were filled with tears.

He stood there for a long time, trying to still the ache in his heart. Then he turned his face toward the south. He must get back to Casson.

Dear old Casson! Kind old Casson! His heart thrilled with affection. He, at least, was left to him.

It was not the first time that Bomba had been away over night from the hut that sheltered him and the old naturalist. He was the provider of food, and his hunting trips had often carried him far afield. But he was always uneasy when that occurred and anxious to get back as soon as possible, for Casson was in no condition to be left alone any more than was necessary.

Having made sure that the revolver, the harmonica, and the matches were safely bestowed in his pouch, Bomba started on his homeward journey.

Refreshed by his night’s sleep and good breakfast, he made good progress for the first two hours. Then his exertions began to tell and his pace slackened, though he was still making remarkably good time, considering that for part of the way he had to hack a path through the underbrush with his machete.

On his way he passed the place of his encounter with the cooanaradi. Only the skeleton of the snake remained. And from the cleanness with which the frame had been stripped, Bomba conjectured that the ants had been at work.

Some distance further on, he came upon the ashes of a fire. Some of the embers were still smouldering and scraps of meat lay scattered about. Some natives out on a hunt had evidently stopped there for a meal.

This was a common enough occurrence and gave the lad no special concern. The Indians of the vicinity, though not especially friendly, were not hostile. They were uneasy at the presence of the whites, whom they looked upon as intruders, but up to the present they had been content to leave them alone, and Casson and Bomba on their part had held aloof from the natives as much as possible.

So Bomba was not alarmed when he caught sight of an Indian a little to one side but moving along on a forest trail that crossed the one that he was pursuing. They reached the junction of the trails at about the same time. The Indian turned and looked at the lad.

Bomba’s heart gave a sudden leap. He saw a symbol painted in ochre on the Indian’s chest. It was the symbol of the head-hunters, the ferocious tribe from the Giant Cataract!

CHAPTER VI

IN THE PUMA’S DEN

Bomba had never before come face to face with a member of the tribe of head-hunters. Only at rare intervals had any of these men of evil omen invaded that section of the jungle where he and Casson lived.

But when they had come they had left behind them a wake of death and destruction. They were cruel and ruthless. They sought for heads as the North American Indians used to seek for scalps with which to adorn their wigwams and testify to their valor.

One of these dreadful trophies hung at the belt of the Indian who now stood regarding Bomba with a scowl that sent a chill to the boy’s heart.

But Bomba let no sign of apprehension show itself on his face, which had been schooled to repression and self-control by his jungle experiences.

On the contrary he smiled amicably and put up his hands, palms outward, as a sign of peace and good will.

“Good hunting, brother?” he asked, in the language that with certain variations was common to all the tribes of the region and with which he was perfectly familiar.

“Ugh!” the Indian grunted noncommittally, as he scanned Bomba with glowering eyes that had in them nothing of friendliness. “You white boy?”

“Yes,” replied Bomba.

“You live with white man that has long hair and walks with a stick?” pursued the Indian.

Bomba nodded.

“The white man bad medicine,” said the Indian, his scowl deepening and his hand tightening on his spear.

“He is good medicine,” declared Bomba.

“He is a Man of Evil,” was the reply. “He bring trouble on my people. Much sickness. Many die. Chief Nascanora very angry. He make talk with big medicine man, and medicine man say there will always be sickness as long as white man stay alive.”

A thrill of apprehension ran through Bomba.

“Old white man is good man,” he protested energetically. “He hurts nobody. He would like to cure people, not make them sick. He has been here many years. He is a brother. He has a good heart.”

“He is a Man of Evil,” repeated the other doggedly. “Medicine man say so. Medicine man know. Tribe will have trouble, much trouble, unless old white man die.”

Bomba tried to collect his thoughts, which had been thrown into a tumult by these ominous words. It came to him that perhaps this man was an emissary of death chosen by the tribe to accomplish its purpose. If this were so, Bomba, boy though he was, would have been ready to do battle with him for the life of Casson.

But if the man were not alone, if companions were near at hand, that would put another aspect on the matter. Then craft and strategy would have to make up for the disparity of numbers.

“My brother has come a long way,” Bomba said, changing the subject. “The home of his people is near the Giant Cataract. Why has my brother come so far from his own people to do his hunting alone?”

“I am not alone,” was the answer. “Many of my people are near me. If I call, they will come.”

Bomba had learned what he wanted to know. This was but a straying member of a large party. The news was not reassuring, but it showed him where he stood. At all costs he must avoid a combat at this moment.

His revolver, fully loaded, was at his belt and, despite his unfamiliarity with the weapon, he could not have missed at such close range. But the report would have summoned the man’s companions, who were probably not far away.

So he restrained his impulse to draw it, and without any betrayal of fear smiled into the man’s face, waved his hand carelessly in farewell, and passed on. In a moment the jungle had swallowed him up.

The Indian had made an instinctive movement with his spear, and then checked himself and stood undecided. The dauntless bearing of the boy disconcerted him.

Bomba, the instant he felt sure that his movements were hidden from the native, dropped his careless attitude and made his way with all the haste of which he was capable through the jungle. He must reach their hut as soon as possible and warn Casson—poor, helpless, old Casson—who would be an easy prey if the enemy came upon him unawares.

He had not gone far before he heard a loud shout behind him. This was followed a moment later by answering shouts from many directions.

He knew at once what they meant. The Indian had summoned those of his companions who happened to be within earshot. There would be a hurried gathering, a hubbub of exclamations, and then, like a pack of wild animals, they would be upon his trail.

Bomba was as lithe and strong as a young panther, and if the going had been reasonably clear, he could probably have distanced the head-hunters. But he had the disadvantage of having to make a path in many places as he went along. He had to hack his way often through tangled thickets, and this took up precious time. His enemies, on the contrary, could follow without stopping the very path that he had made with infinite labor. It was one of the ironies of his situation that he was making the way easier for his pursuers. He was actually helping them to overtake him.

Under such conditions, it was only a matter of time before they would catch up with him. Already he could tell by the crashing of the underbrush that they were nearer.

But he kept on, spurred by desperation. His lungs were laboring, his breath coming in shorter and ever shorter gasps. He was reaching the limit of his endurance. The end could not be long delayed.

As his eyes roved frantically from right to left, he caught sight of an opening in the side of a small knoll a little way off from the direction in which he was headed.

His pursuers were close behind him now. At any moment the foremost of them might appear in sight.

Like a flash, Bomba turned in the direction of the cave and bolted into it headlong, pitching at full length on the ground within.

He lay there in the semi-darkness panting heavily, trying to regain his breath, the little that he had left having been knocked out of him by the fall.

He could hear the rush of the pursuers as they passed by in the direction he had been heading, and he breathed a sigh of heartfelt relief as he heard their steps receding in the distance. For the moment he was saved.

But he knew this was only a reprieve. It would not be long before his enemies would realize that they were on a false trail. They would miss the sound of his steps, the marks of his machete on the bushes. Then they would retrace their steps and search every nook or cranny in which he might be hiding. And they could hardly fail to discover the cave!

As soon as he could breathe again, he rose to his feet and reconnoitered the hiding place that had, temporarily at least, proved his salvation. What his eyes could not see his touch supplied.

There was no apparent exit from the cave except the opening through which he had come. But at the back, partly hidden by a shelf of rock, was a small crevice only a few inches wide. It seemed impossible at first that it could permit the passage of his body. But by placing himself sidewise and drawing in his breath he finally managed to worm his way through and found footing on the other side.

Now he could breathe more freely. He could crouch down in the narrow passage behind the crevice and be concealed from the sight of anyone at the entrance of the cave. To a casual observer the cave would seem empty.

And even if a careful search were made and his hiding place discovered, he would be in a natural fortress. No arrow or spear could reach him. An Indian would be too big to wriggle through that crevice, and if he tried to do so, he would be at the mercy of the lad’s knife or pistol while he was making the attempt.

The first glow of exultation had barely subsided when Bomba could tell by the sounds outside that his enemies were returning. He could hear a babble of voices and grunts of rage and disappointment at the escape of their prey.

He crouched low behind his barricade, scarcely daring to breathe.

The steps came nearer and nearer.

Then suddenly there was a guttural exclamation of surprise mingled with triumph, and he knew that they had discovered the entrance to his hiding place.

The shout was followed by dead silence, which Bomba was at no loss to interpret.

His enemies knew that if he were there he would be desperate, fighting with his back against the wall. None of them was eager to be the first to enter and face him. There was no need for impetuous action. If he were there, he could not escape.

So they were drawing stealthily nearer, probably from the side, so as to escape a possible whizzing arrow, the only weapon with which they thought he would be equipped.

For some minutes the deathlike silence continued. Bomba could feel, though he could not see, that fierce, keen eyes were peering in, trying to pierce the darkness that at the back of the cave was almost absolute.

Then came a hissing sound, and a flaming torch was thrown into the cave, its flaring light illuminating every crevice of the interior.

Apparently it was empty. If the fugitive had entered there, it seemed evident that he must have escaped by some other exit.

To discover that other exit, if there were one, several of the Indians crowded into the cave, and one of them picked up the torch to make a more thorough search.

He had scarcely done so before a terrific hubbub arose from his companions on the outside of the cave. Something had frightened them.

The men within rushed out, and there was a snapping and crashing as the whole party forced its way through the underbrush, evidently in panic flight.

What had happened? Bomba asked himself. Was one terror to be succeeded by another?

He listened with all his ears. There was no sound except that caused by the stampede of the Indians, now steadily growing fainter.

Minutes passed and still no sound. The strain became unendurable.

Slowly, very slowly, Bomba raised his head and peered over his barricade.

All he saw was a shadow.

But that was enough to chill his blood.

For the shadow that lay on the ground before the cave was that of a giant puma, one of the fiercest inhabitants of the Amazonian wilds!

The owner of the cave had returned!

CHAPTER VII

A SIEGE OF TERROR

For a few moments Bomba’s heart seemed to cease beating.

Down he went again behind his barrier, while he tried to collect his thoughts in the presence of this new peril.

The thought that this might be the den of a wild beast had occurred to him when he first saw the mouth of the cave, but it had been crowded out by his desperate need of escaping from his human enemies.

Now he realized that he was trapped. There was not one chance in a hundred that the beast would stay outside for long. Sooner or later it would enter the cave to rest in readiness for its nocturnal hunting. And when it did come in, discovery would be certain.

In Bomba’s crouching position the animal could not see him. But it would smell him and follow the scent to the crevice in the rock.

To be sure, it could not get at him. Its huge body could not squeeze through the narrow opening. But when it once became convinced of this it would settle down to a long siege that would doom its captive to certain starvation.

Once more Bomba ventured a peep at the shadow. It had changed its shape. At first the beast had been standing. Now the shadow showed that it was stretched out on the ground, but with its head uplifted, watching perhaps for the possible return of the Indians that its coming had frightened off.

That shadow had a dreadful fascination for Bomba. He watched it as though under a spell, waiting for the moment when it would change in shape, when the great tawny beast would rise, shake itself, yawn, and at last enter the cave.

In the position in which Bomba found himself, he could use what weapons he had only with great difficulty. The passage was so narrow that he had no room to draw his bow. That rendered his arrows useless.

And the crevice was so located with reference to his body that he could only use his knife or revolver with his left hand.

As to hurling his knife, as he had in the case of the jaguar, he could not draw his arm back to get sufficient force for the throw. And he was so little used to the revolver, even with his right hand, that the chance of his being able to aim accurately with the left was almost negligible.

His heart sank as he realized his helplessness. He seemed doomed to die like a rat in a trap.

While he was bitterly pondering his situation, the shadow moved. Like a shot Bomba’s face disappeared from the crevice through which he had been peering, and he crouched down low, fearful lest the beast should even hear the sound of his heart thumping against his ribs.

He could hear the padding feet of the puma as it leisurely entered the cave. Then there came a sudden pause, a sniff, an ominous growl.

The beast had scented the proximity of a human being. Bomba knew that its hair was bristling, its eyes glowing, as they roamed about seeking to discover the whereabouts of the intruder.

Then the padding was resumed, and the steps drew nearer his hiding place.

There was a thunderous roar and the beast dashed violently against the wall, as though it would batter it down by the sheer force of its impact.

Three times this was repeated. Then, as though recognizing the futility of this form of attack, the animal desisted. The roars were replaced with snarls, as the puma tried to force its body through the narrow opening.

It struggled viciously to get through, but its huge bulk prevented. Foiled in this, it reached one of its great paws through the opening and swung it about, trying to get a grip with its claws on whatever was in that passage and drag it out within reach of its jaws.

Bomba shrank as far away as possible, being just able to escape the sweep of the powerful claw that would have torn into ribbons whatever it clutched.

Again and again the baffled beast sought to reach its prey, but without success.

At last it desisted and paced the floor of the cave with growls and roars that in that narrow space were almost deafening. Then it settled down to a siege. Its instinct told it that sooner or later the trapped enemy must die of starvation, or come out to meet a fate quicker but more terrible.

Bomba felt sick and weak under the strain. He had escaped that terrible paw only by inches.

His only chance seemed to be that the beast at last might sleep. Then Bomba might creep through the narrow opening and either steal from the cave or at least have elbow room to battle for his life with knife and revolver.

But he dismissed this forlorn hope even as it came to him. If the beast should doze, it would be so lightly that even the slightest sound, the fall of a leaf, would awaken him. He would be on Bomba before the latter had squeezed through the opening. There was no hope from that quarter.

And with dread for his own safety was mingled the agonizing thought of what might happen to Casson, unwarned and helpless before the storm that was brewing. Even at this moment the head-hunters might be on their way to the lonely cabin.

An hour passed by. The snarls had ceased, but Bomba could hear the stertorous breathing that told him the beast was still there, watchful and relentless as fate.

At last he ventured a look. With infinite caution he applied his eye to the crevice in the wall. There lay the beast, a monster of its kind, its unblinking eyes turned in his direction.

But those fierce eyes had no terrors for Bomba!

Astonishment, relief, delight chased themselves over the lad’s features.

His mouth opened and a low crooning sound issued from his lips, rising and falling in a weird jungle melody.

The effect on the puma was magical. It started to its feet. The fierce light faded from its eyes, and was replaced with a look of pleasure and benevolence. Then it commenced to purr.

“Polulu!” murmured Bomba. “Polulu! It is Bomba speaking—Bomba, your friend.”

The purring grew louder, and the great beast came and rubbed itself against the wall.

Bomba hesitated no longer. He forced his body through the crevice without the slightest trepidation, though with some difficulty, for already the puma was rubbing his head against him, fawning upon him like a cat, and trying to lick his hand.

“Polulu. Polulu,” murmured Bomba, as he caressed the great head fondly. “Why did I not know it was you? I would not have hidden from you. You have given Bomba a great fright.”

Polulu purred still more loudly and rubbed his head so hard against Bomba as to almost knock him over. Then the beast lay down and rolled over and over to testify his joy at the meeting.

For the last two years a warm affection had existed between the two. It had taken birth at the time the big puma had been caught by a falling tree that had imprisoned and broken one of its hind legs.

Bomba had come upon the tortured animal at a time when it was suffering terribly and biting savagely at the injured leg. The boy was stirred with compassion. He had a strange power over animals, and the puma had sensed his sympathy.

Bomba had brought the animal food and water. Then he had set to work to free the trapped leg. This accomplished, he had set and bound up the injured member, the puma submitting to the treatment because it knew instinctively the kindness that prompted it.

Many days had passed before it was able to stand and get about, and during all this time Bomba had supplied its needs and nursed it back to health. By the time this was accomplished, the puma had all the affection for Bomba that a pet cat has for its master.

Repeatedly since then the paths of the two had crossed in the jungle, each time to the joy of both. At times, Polulu had been accompanied by its savage mates that would have attacked the boy had not Polulu taken him under his guard and warned the others that the boy must be immune.

For some minutes Bomba fondled and caressed the great beast, which responded with equal affection and manifestations of delight.

Then the pressing need for haste forced itself on the boy, and with a parting pat on the tawny head he rose and issued from the cave.

Polulu was disappointed at the briefness of the lad’s stay, and made as though he would go with him. But Bomba gently waved him back and the puma obeyed meekly. And in the lambent yellow eyes that stared after him Bomba could read regret and desolation.

Immeasurably relieved in mind as the boy was at his unexpected escape at the moment that death had seemed to be closing in on him, he was tormented by the thought of the precious time that had been lost by his enforced stay in the cave. Now he must redouble his speed, at the same time keeping a sharp lookout for the marauding Indians.

He came to the banks of a wide stream that wound in a sweeping curve through the jungle. To swim across it would save him a long detour on land and at least an hour of time.

Ordinarily he would have taken the land route, with whose dangers he was more familiar and better able to cope. He had a deep fear of the caymans, the great South American alligators, that infested many of the streams.

He could swim like a fish. But the alligators could also make amazing speed, considering their clumsiness. And in the water the only weapon the boy could use effectively would be his knife, and that would be but of slender use against such a formidable foe.

He knew, however, that at this time in the day the alligators would be apt to be sunning themselves on some of the islands that studded the stream at intervals. One of these islands he could see at a little distance, with dark forms like so many logs fast asleep on the sands.

His resolve was made on the instant. He would take the chance.

Silently as a shadow he slipped into the water, and, swimming so smoothly that he scarcely left a ripple behind him, he moved toward the point he had in view.

He had traversed more than half the distance and was already beginning to congratulate himself on the successful outcome of his venture when he heard a splash behind him.

Something had broken the surface of the water.

He looked behind him and his heart skipped a beat.