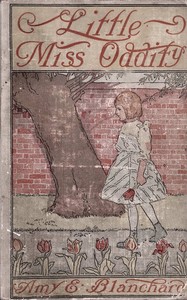

Read and listen to the book Little Miss Oddity by Blanchard, Amy Ella.

Audiobook: Little Miss Oddity by Blanchard, Amy Ella

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LITTLE MISS ODDITY ***

Transcriber’s Note Italic text displayed as: italic

LITTLE MISS ODDITY

[Illustration: “‘TAIN’T NOTHIN’ BUT AN OLD WEED!”]

Little Miss Oddity

By AMY E. BLANCHARD

Author of “A Dear Little Girl,” “Mistress May,” etc.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY IDA WAUGH

[Illustration: Decoration]

PHILADELPHIA GEORGE W. JACOBS & CO. PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1902, By GEORGE W. JACOBS & CO. Published July, 1902.

Contents

CHAPTER. PAGE.

I. THE BACK YARD 9

II. IN THE GARDEN 29

III. WHERE IS JERRY? 47

IV. A NEW ACQUAINTANCE 67

V. THE VISIT 85

VI. PLEASANT DREAMS 105

VII. HOW CASSY TRIED TO MAKE A FIRE 119

VIII. THE SUMMER LONG 141

IX. NEWS 157

X. PLANS 175

XI. THE SURPRISE 191

XII. UNCLE JOHN ARRIVES 209

Illustrations

“’Tain’t nothin’ but an old weed” Frontispiece

Every now and then Flora was carried over and shown the geranium Page 53

They played all sorts of games ” 99

Cassy’s eyes opened wider and wider ” 133

“What do you think! News! News!” ” 163

THE BACK YARD

CHAPTER I

It was a queer jumbled up place, that back yard of the house where Cassy and Jerry Law lived; old barrels tumbled to pieces in one corner, empty tomato cans rolled against cast-off shoes in another; here bits of broken crockery wedged themselves in between a lot of shingles, and there a pile of iron scraps crowded against a bottomless chair; on a clothes-line flapped several pairs of overalls and a stunted little tree bore upon its branches sundry stockings of various sizes and conditions.

It was a discouraging looking place, but Cassy, intently bending over a pile of dirt near the bottomless chair, did not heed anything but the fact that two tiny green shoots were poking themselves up from the unpromising soil. She was a thin-faced, bright-eyed child, not pretty, but with an eager, wistful expression, and as her face lit up with a sudden smile she looked unusually intelligent.

“Jerry, come here,” she cried; “I’ve got a garden.”

“Sho!” returned Jerry, “I don’t believe it.”

“I have so; just you come and look at it.” Cassy tossed back the locks of brown hair that hung over her eyes and softly patted with her two small hands the dry earth around the springing blades of green. Jerry came nearer. “It’s truly growing,” Cassy went on. “I didn’t stick it in the ground myself to make believe; just see.”

Jerry bent his sandy-colored head nearer to the object of his sister’s admiration.

“’Tain’t nothin’ but a old weed,” he decided at last.

“How do you know?”

“I just believe it.”

“Well, you don’t know, and I think it is just as good to believe it will grow to be a beautiful flower.”

“I wouldn’t count on that,” Jerry said.

“Why not?”

“’Cause.”

“But just maybe,” Cassy insisted pleadingly. “Why couldn’t it? I don’t see why not.”

“’Cause,” repeated Jerry, “I never saw no flowers growing in this back yard.”

“But Mrs. Boyle has some right next door, and oh, Jerry, Mrs. Schaff across the street has some great big lovely red ones. Please let’s hope this will be a flower.”

“Well,” replied Jerry, doubtfully, “I’ll pretend, but if it isn’t, you mustn’t say: Now, Jerry, what made you let me believe in it?”

“I won’t; I truly won’t.”

“All the same,” said Jerry, “I don’t see how you can keep it from being trampled on.”

Cassy looked alarmed.

“You see it’s right out here where anybody can pull it up or do anything. Billy Miles would rather tear it to pieces than not if he thought you wanted to keep it.”

Cassy’s distress increased. “Couldn’t we hide it or something?”

“We might for a little while, but if it should grow and grow why then anybody could find it out.”

“Oh, dear,” sighed Cassy, “it’s like Moses when they had to put him in the bulrushes. Maybe it will be a little wee bit of a flower and after a while we could come and dig it up and set it in the window. I know what I’ll do; I’ll set that old chair over it and then maybe nobody will notice it.”

“There’s a piece of chicken wire off over there,” said Jerry, good-naturedly. “I’ll get that and sort of twist it around the chair, then it will make a fence for it. Sh! There’s Billy, and if he sees us he will play the mischief with any fun of ours.”

Cassy arose hastily to her feet and faced the back door from which Billy’s form was just issuing. There was no love lost between Billy and the Law children.

“What yer doin’?” questioned Billy, looking suspiciously at Cassy’s defiant attitude.

“Nothin’.”

“Humph! I don’t believe ye.”

Cassy spread out her hands.

“Well, see, am I doing anything? Did you think I was eating strawberries or swinging in a hammock?”

“You’re too smart,” returned Billy. He came over and peered around. “You’ve got somethin’ in among those cans.”

Cassy tossed up her chin.

“You’re welcome to all you find in them.”

Billy turned one over with his foot, looked among the scraps of iron and then said:

“You’re just bluffin’, but I’ll find out.” And he climbed the fence into the next yard.

As soon as his stout legs had disappeared Cassy whirled the old chair around till it stood over her treasured plant. Jerry disengaged the strip of chicken wire from its surroundings and contrived a sort of coop-like structure which did not attract the eye, yet kept the small green shoots safely hidden without excluding the light and air.

“Now let’s go tell mother,” said Cassy, and took to her heels, Jerry following.

Up the shabby dark stairway they ran, Cassy stepping lightly, Jerry, boy-like, with clattering tread. Mrs. Law glanced up from her sewing as they entered. “We’ve got a garden,” said Cassy in a loud whisper.

“What do you mean?” inquired her mother, breaking off her thread with a snap.

“We have truly,” Cassy insisted. “It’s under an old chair in the back yard.”

“That’s a queer place for a garden,” responded her mother, rethreading her needle and taking swift stitches.

“Yes, but it happened itself, you know, and so we have to have it there. We’re so afraid Billy Miles will pull it up. Jerry thinks maybe it’s a weed, but we’re going to hope it’s a flower, a real flower. What would you like it to be, mother, a rose?”

“I’m afraid that would be setting my hopes too high. Let me see, perhaps it might be a morning-glory.”

“Are they pretty, morning-glories?”

“Yes, very.”

“What color?”

“All colors, but the common ones are generally purple or blue.”

“I’d like them to be blue. What do they look like?”

“They grow on a vine, and the flowers are little vase-like cups that open first thing in the morning and close when the sun shines on them.”

“But they open the next day?”

“No, not the same flower, but others do. They bloom very freely, although each one lasts only a little while.”

“Do they smell sweet?”

“I never noticed that they did.”

Cassy was not entirely satisfied with this description and sat very still thinking about it. After awhile she broke out with: “You don’t think it could be any other kind of a flower?”

“Oh, I didn’t say so. Of course it might be. We can tell very soon. I know the leaves of a morning-glory, and when I get time I will go down and look at your plant. Yes, I know morning-glories well enough. There used to be a great mass of them over the back fence where we used to live; all colors, blue and pink and lovely white ones striped. I used to think they were very beautiful.” She sighed and worked faster. “Don’t go out, Jerry,” she said presently. “This work must go home this evening.”

“May I go with Jerry?” asked Cassy.

Her mother hesitated and then replied, “Yes, but don’t stay.”

Spring was well on its way as open windows and doorsteps swarming with children showed, but in this narrow street there were no perfume-laden airs; it seemed instead that all the foul odors were made more evident by the warmer weather, and as the brother and sister made their way through the slovenly groups of loungers, there was little to make them realize the beauty of a world where green trees and sweetly smelling orchards made the heart glad.

They took their way along soberly enough, Jerry lugging the big bundle and his sister trotting along by his side. From the narrow street they turned into a broader one where shops of all kinds were arrayed along the way. Into one of these the children turned, delivered their bundle and hurried out. They never tarried long at the place, for they did not feel comfortable under the old Jew’s sharp eyes, and did not enjoy being stared at by the two big boys who were always there, too.

“We did hurry,” said Cassy when they reached the corner. “And see, Jerry, there are trees with tiny green leaves on them behind that wall. I have always wanted so much to see what was behind that wall. Do you believe you could climb it?”

“Yes, ’course I could, but the cops wouldn’t let me.”

“I do want to know so much,” repeated Cassy wistfully. “There is a gate, you know, but it’s boards, and it’s always shut tight. Can’t we walk around that way now? It won’t take us long and it’s so much nicer than the other way.”

“I don’t know why,” said Jerry. “Brick walls ain’t so awful pretty.”

“No, but the trees are getting green; little bits of baby leaves are coming out on them and we can see them above the wall. Let us go that way.”

“All right,” agreed Jerry.

They trotted along till the brick wall was reached and then Cassy exclaimed excitedly: “Oh, Jerry, I believe the gate is open; there is a man there with a wheelbarrow. Oh, do hurry.”

She ran forward as fast as her legs would carry her and sure enough the gate was open and beyond it smiled such a garden as Cassy had never before seen. Tulips, red and yellow, flaunted themselves in their little round beds, daffodils nodded sunnily from the borders, primroses and pansies, flowering bush and early shrub were all in bloom. Cassy drew a long breath of delight. Was ever anything ever so beautiful? Her eager little face was bent forward and her big eyes were taking in the whole scene when the gardener came out trundling his wheelbarrow.

“Take care, sis,” he warned, “don’t stand in the way.”

“Oh!” Cassy exclaimed, scarcely noticing what he said. “Oh, isn’t it beautiful?”

The gardener smiled.

“’Tain’t so bad. You can step inside the gate out of the way, if you want to.”

“And Jerry, too?” Cassy asked as her brother came up.

The gardener looked suspiciously at Jerry. He had reasons for not thinking well of small boys.

“He’d better stay outside,” he said; but seeing Cassy’s disappointed face he yielded. “If you’ll keep right there by the gate I guess you’ll do no harm,” he told Jerry, and the two children stepped inside.

Such a waft of sweet odors as met them, and such a glory of color. The gardener glanced at Cassy’s rapt face as he trundled in his last load of sand, and he looked pleased.

“You like it pretty well, don’t you?” he said. “If I had time I’d show you about, but I’ve got to get some plants potted before night, and I’ve got to shut the gate now,” he added regretfully.

Cassy turned slowly, her eyes still lingering upon the borders.

“She’s wanted to see the inside of this place more’n anything,” Jerry confided to the gardener as Cassy’s steps lagged, “but the gate ain’t ever been open before.”

“Then I’m glad it happened to be this time when you were by,” said the gardener heartily. “Some day if you happen to see me when I’ve got time I’ll take you all over the garden.”

“Oh, thank you, sir, thank you. I’d love that. Have you any morning-glories?”

The man laughed.

“No, pesky things; they grow so fast that they’d get the best of me in no time; though, now I think of it, there were some by the kitchen door last year. The cook planted them, and I guess they’ll come up again this summer too plentiful for my use. Do you like ’em, sis?”

“I never saw any,” Cassy told him. “But I want to.”

She turned away as the gardener made ready to shut the gate, and all the way home she had scarcely a word to say. “It was like the garden of Eden,” she said under her breath once.

“I think he might have given us some flowers,” said Jerry.

“Maybe he couldn’t,” returned Cassy. “They aren’t his. I think he was very good to let us go in. Oh, Jerry, how happy, how happy people must be who have a garden like that.”

There was excuse enough for their having tarried when they reached home at dusk to find their simple little supper of mush and molasses ready for them. Cassy could talk of nothing but the garden, and all night long she dreamed of nodding flowers and green trees.

In the morning her first thought was of the two green shoots under the old chair in the back yard. Perhaps the plant needed water; she would go down and see before any one was up. Carefully carrying a cupful of water she went down the rickety steps which led to the back yard.

The little green shoots had stretched further up out of the dry earth, to the child’s delight. Lifting the chair with a cautious look around she poured the water upon the earth and watched it sink into the ground. She crouched there for some time as if she would discover the plant’s manner of growing.

At last she arose with a sigh. Such a poor little garden compared to the one she had seen yesterday, but what possibilities did it not hold? This tiny plant might yet show gorgeous blooms of red and yellow, or send forth big bunches of pink. Her thoughts went rioting along when they were interrupted by a hoarse laugh, and looking up startled, she saw the grinning face of Billy Miles peering over the fence.

“I caught ye,” he jeered. “I seen ye. What yer got buried there?”

“Nothing,” returned Cassy stoutly.

“Yer another,” retorted Billy, clambering over the fence. “What yer got in that cup?”

Cassy turned the cup upside down, but Billy was not satisfied. He came threateningly towards her, taking no heed of where he was stepping.

“Oh, take care,” cried Cassy, forgetting caution in her alarm lest his heavy tread should crush her precious plant.

Billy looked down.

“Ye tried to fool me,” he cried, seeing the moist circle out of which stretched the green shoots.

“I didn’t, either.”

Billy for answer gave a savage kick and snap went the little stalk. Cassy burst into tears, picked up her treasured plant and went flying up-stairs. She laid the tiny stalk before her mother, and hiding her face in her hands sobbed bitterly.

Jerry, still frowsy and unkempt, issued from his bit of a room.

“What’s the matter?” he asked, looking at Cassy in concern. For answer Mrs. Law held up the broken stalk, and Jerry looked his sympathy.

“Never mind, don’t cry so, dear,” Mrs. Law said at last. “Very likely it wouldn’t have lived anyhow.”

“How did it happen?” whispered Jerry.

“Billy Miles,” Cassy whispered back, choking down her sobs. “He saw me watering it and he got mad and kicked it to death. Oh, my poor little flower that was going to be a morning-glory. It was, wasn’t it, mother?”

Mrs. Law examined the broken leaves.

“I think perhaps it was,” she replied.

“Won’t it live if I plant it in a box?” asked Cassy, this new hope causing her tears to cease.

“I’m afraid not.”

“I’ll get even with Billy Miles,” muttered Jerry; then louder he said, “Cheer up, Cass; I’ll get you a real, righty flower, see if I don’t.” He looked at his mother for encouragement.

“How will you do it?” asked Cassy, interested.

“Never you mind. I will, honest, I will. I’ll tell mother.” And drawing Mrs. Law to one side he confided to her his plan.

All day long Jerry was absent, and when Cassy asked where he was, her mother only smiled, though if the truth were known he was not very far away, for he was keeping watch by the gate in the garden wall. If that gardener should but once appear Jerry knew well what he meant to do. He did not come home even to dinner, but munched a crust he had stuffed in his pocket, and kept his eye on the gate.

“He might just be coming out to dinner now,” the boy murmured to himself, “and I’d be sure to miss him if I left.” But no gardener appeared till late. The clock had struck six and the streets were full of workmen returning to their homes when the gate did open and out stepped the gardener, dinner bucket in hand. He had no sooner appeared than Jerry met him, outwardly as bold as a lion, but inwardly anxious.

“Mr. Gardener,” he began.

The man scowled down at him.

“What’s wrong?” he asked. “Out with it.”

“Nothing much,” returned Jerry, “at least, you see—you know me and my sister were here looking at your garden yesterday.”

“Yes, I remember now. Well?”

“And you know—” Jerry went on to tell his story of the broken plant, concluding with: “so I thought some time, you know, you might have an extra plant, just a little bit of a one, that you wouldn’t miss, and if you’d sell it cheap, I’d work it out, the pay, I mean. I could help to wheel that sand, you know.”

The man’s face broke into a smile.

“All right, sonny; it’s a bargain. I must go home now, but you come around Monday, and sister shall get a plant.”

“Shall I come to this gate?” asked Jerry eagerly. “When?”

“No, not here; round at the other side. We don’t often open this gate, only to take in loads of dirt and such, and when I am late I go out this way. You go all the way around to the other side and you’ll see an iron railing; there’s another gate there; go in and knock at the back door and say you want to see John McClure. Come about twelve o’clock and bring sissy.” He nodded and passed on, leaving Jerry in a state of extreme satisfaction, and ready to make for home with scurrying legs and a large appetite.

IN THE GARDEN

CHAPTER II

“Where have you been all day?” Cassy asked as Jerry came blundering in.

“You can’t guess,” he returned.

“Down by the wharf?”

Jerry shook his head. “Somewhere you like. I stayed outside ’most all day, but I got in at last; you know where.”

“Not the garden.”

“Yes, sir, the garden, and what’s more we’re going to see it on Monday. I had a talk with the gardener; his name is John McClure.”

“Really?” Cassy clapped her hands.

“Yes, really.” Jerry winked at his mother. That was not all there was to tell, but he meant to keep the rest a secret.

“I’m glad it’s Saturday night,” said Cassy after a silence, “for now I’ll have all the time I want for thinking about it, for I’ll have no lessons to study and to bother me. Besides, mother won’t have to work to-morrow and she can tell us all about the house where we were born. How long has it been since we left it, mother?”

“Six years,” Mrs. Law told her.

“I remember it a little,” said Jerry. “I remember father, too.”

“I wish I did,” said Cassy sorrowfully. “Don’t let’s talk about that now. Tell us what you did to-day.”

“I went to market and did my errands first, but there were not many baskets to take home this morning, and then I went and sat out on the curbstone by the wall and waited. Gee! but that’s a big place; it takes up ’most a square, and it’s awful pretty up there. I saw a shiny carriage stop at the door and a lady and a boy got out. I’d like to be that boy.”

“Was he just your size?” asked Cassy, interested.

“No, lots bigger, but he looked friendly; he kind of smiled when he saw me there.”

“Come, children, it’s cleaning up time,” said Mrs. Law. “We must get ready for Sunday; my last buttonhole is finished. I expect Jerry is as hungry as a bear.”

“I am as hungry as two bears,” Jerry assured her. “What are we going to have for supper? I don’t care much what it is, so there is enough of it.”

“Don’t tell him what it is,” said Cassy.

Jerry approached the little stove where something was simmering and sending out savory odors. He lifted the lid.

“Stew!” he cried.

“Yes, with dumplings in it. You shouldn’t have taken off the lid, Jerry, it will spoil them.”

“Never mind, it is all ready to dish up,” Mrs. Law told him.

“My, but it smells good,” said Jerry with much satisfaction. “Did you make plenty of dumplings, mother? They are jolly good with molasses on them.”

“I hope I made enough,” his mother told him. “Cassy and I did not take a hearty dinner, for you were not here, and so we decided to have a hot supper.”

“We don’t have such good things every day,” Jerry remarked, drawing up his chair. “I wonder if we’ll ever have lots and lots to eat; meat every day and dessert. My! it must be fine. I’ll bet that boy I saw to-day has all that.”

“I don’t believe he has dessert every day; I don’t believe anybody has,” Cassy asserted, eyeing her mother as she dished out a plentiful supply of stew upon Jerry’s plate.

“Ho! I’ll bet some people do. Don’t you, mother?”

“Why, yes, of course.”

“Did you use to?” Cassy asked.

“I believe we did.”

“Were we as rich as that?” Cassy looked her surprise.

“We were not rich at all, but we were very comfortable and very content.” Mrs. Law gave a little sigh.

“Just wait till I grow up, and we will be again,” said Jerry, pausing with a big piece of dumpling on his fork.

“That’s so long,” sighed Cassy.

But to Jerry with a plentiful meal before him to-morrows were pleasant anticipations, and he replied: “Pshaw! no it isn’t.”

Cassy glanced up and caught her mother’s tired look.

“Well, no it isn’t,” she agreed; “it won’t be any time, and I’ll be grown up, too, and mother won’t have a thing to do but——”

“‘Sit on a cushion and sew a fine seam,’” Mrs. Law put in.

“‘And feed upon strawberries, sugar and cream,’” Cassy finished the line. “I saw strawberries in one of the shops yesterday.”

“I’d rather have dumplings any day,” Jerry decided, having finished eating his stew, and being now ready to attack the dumplings and molasses. To tell the truth, the dumplings formed the principal part of the stew and the meat was very scarce, but the children rather rejoiced at that, and completed their meal with much satisfaction. Then there were many little duties to be done, and of all the rooms in the tenement it is safe to say that Mrs. Law’s was in decidedly the best order for Sunday.

Cassy could hardly wait till noon time Monday, and though she was usually a pretty good scholar, she made many mistakes that morning, and was only aroused to a sense of her inattention when it suddenly dawned upon her that she might be kept in and that would be a calamity too dreadful to contemplate.

At last twelve o’clock came, and she found Jerry waiting outside the school door.

“Come along,” he cried. “We don’t want to lose any time.” And catching her by the arm he hurried her along the street till they reached the long wall.

“Aren’t you going to wait at the gate?” Cassy asked as Jerry, without pausing, went on.

“No, we are to go around to the other side. ’Way round where the horses go into the stable.”

They found no difficulty in getting in, and, after walking the length of the garden path, they came upon their friend, the gardener, sitting on a wheelbarrow. He looked up as they came near.

“Well, here you are,” he greeted them cordially. “Didn’t forget the time. Sun’s noon high and a few minutes past. Now then, my little lass, we’ll go find your plant; I’ve got it safe and sound for you.”

Cassy’s eyes opened wide.

“My little plant?”

“Yes, didn’t brother tell you?”

Cassy shook her head.

“You’re a sly little lad,” he said, pinching Jerry’s ear. “I thought that was what you came for.”

“I thought it was just to see the flowers,” said Cassy.

“You can do that, too, but we’ll pick out yours first. I slipped a lot of geraniums a while ago; they’re easy cared for and are good bloomers; no trouble if you give them a sunny window and a little water. Now then.” He stopped before a row of potted geraniums already showing their gay blooms of red and pink. “Take your pick,” he said.

“Oh!” Cassy crouched down and looked lovingly from one to the other. How could she decide among so many? However, finally, after changing her mind frequently, she halted between a crimson and a lovely pink. Then she sought Jerry’s advice, and he spoke for the red one, but Cassy thought her mother would like the pink one; it was such a lovely color, and finally that was selected; Cassy, hugging it to her, fairly kissed the little flower.

“How good you are,” she said. “Oh, Mr. McClure, what a lovely father you must be.”

John McClure threw back his head and laughed.

“I’m no father at all,” he said; “I’m a lone man with neither chick nor child.”

“I think that is a great pity,” said Cassy, gravely. “I have been thinking of you living in a pretty little house with morning-glories climbing over the porch.”

“And all the place I’ve got is a room in a workman’s boarding-house.”

“I wish you did have a cottage.”

“I’ve wished the same more than once, but it doesn’t seem to come my way. Come now, we’ll go see the rest of the flowers.”

“I’m afraid we shall miss our dinner if we do that,” Jerry put in.

“Oh, I’d rather miss my dinner than not see the flowers,” Cassy told him.

“You would?” Mr. McClure looked pleased.

Just then they saw a boy coming down the path. He had a cheery bright face, and Cassy concluded he must be the one of whom Jerry had told her.

“Well, John,” the boy cried, “I see you have company.”

“Yes, Mr. Rock. This young lass here says she’d rather look at the flowers than eat her dinner. What do you think of that?”

“That she’s a girl after your own heart. But why can’t she do both?” The boy smiled down at Cassy as if expecting her to answer.

“Because we couldn’t get home and back to school in time and see the flowers too, and I do so want to see the flowers.” She looked wistfully at Jerry.

“And I suppose your brother would rather eat his dinner,” said Rock. “I think we can manage it. I’ll run in and get you a sandwich or something, so you won’t starve.” He was gone like a flash, his long legs covering the ground with great strides.

“That’s just like Mr. Rock,” said John McClure. “Come along, children, we’ll be looking at the flowers, and Mr. Rock will see that you don’t go hungry.”

“But——” Cassy looked confused. “I—mother——Do you think mother would like it, Jerry?”

“What?” John interrupted. “I’ll venture to say she’ll not object to your taking a bit of a sandwich from Mr. Rock. Just make yourselves easy, and if you think there’ll be any trouble I’ll go and explain it to her myself. By the way, you won’t want to take your geranium to school, sis; you’d better leave it here and call for it on your way home. Come now; these are the tulips.” And he began to guide them around the garden showing them all manner of sweet or showy flowers.

They were not half way around when Rock appeared bearing a tray on which were two glasses of milk, a pile of sandwiches and two generous slices of pie. He set the tray down on a bench under a spreading tree.

“I say, John, it’s a jolly place to eat, out here, this fine day. I’ve a mind to bring something for myself. Don’t begin your lunch, children, till I come back.” And he was off again, returning in a few minutes with more sandwiches, some crackers and half a pie. “Now,” he said, “I call this great. Pitch in, youngsters. Come along, John, bring your dinner-bucket, and we’ll have a lively time.”

Cassy and Jerry were rather shy at first, but Rock soon made them feel at home, and they thought they had never tasted anything so good as those chicken sandwiches and that apple pie.

“There!” exclaimed Rock, as the last crumb disappeared, “I enjoyed that a great deal more than if I had eaten my lunch indoors. I went to the country for over Sunday and when I got back this morning it was too late for school; the train was an hour late. I found mother wasn’t going to be at home to lunch, so, if you hadn’t been here to keep me company, I’d have eaten a solitary meal indoors. By the way, what time do you go back to school?”

Jerry told him, and he pulled out his watch.

“Then you’ll have to scamper,” he cried.

“You’re coming back to get your geranium,” John charged Cassy, and she smiled up at him with such a sunny expression that John saw there was little danger of her forgetting.

“Those are nice little things,” said Rock as he watched the two children depart.

“That they are, Mr. Rock,” returned John.

“I wonder where they live,” said Rock.

“In one of the tenements beyond the square, so they tell me.”

“Pshaw! that’s not a very nice place, and those children seem neat and well-behaved, and they speak well, too.”

“They’re fatherless,” said John, “and it’s likely their mother has a hard time to get along, and can afford to live nowhere else, but they’re different from most of the gang down that way; I saw that the first day when they stood by the gate and looked in.” And he told Rock of how he had first met the children.

“I’m going to learn more about them,” Rock declared. “I’ll be here when they come back after school. That little girl’s face is a perfect sunbeam when she smiles, and the boy is a manly, honest little fellow.”

True to his word Rock was there when the children returned.

“Where do you live?” he asked them.

“On Orchard Street,” they told him.

“Have you always lived there?”

“No,” said Cassy, “we used to live in a lovely little house near the city, and there were morning-glories growing over the porch.” She looked at John.

“By the way,” said that worthy, “I told you I’d see about the morning-glories. I believe I’ve some seed in the tool-house. You’re welcome to ’em, and if you plant ’em they’ll be likely to grow, and you can train ’em over your window. Have you a good yard?”

“No,” Cassy said; “we have three rooms on the top floor, one big room and two little ones. Mother likes it up where we are because it is nearer the sky, and there is no one above us.”

“Sensible woman,” said John, nodding approvingly.

“And you’ve no yard? Well, you can plant the seeds in a box on the window-sill, unless you like to have a garden in the common yard.”

“Oh, we can’t. Billy Miles won’t let us.” And Cassy told the story of her treasured morning-glory, and of its destruction. Rock and John listened gravely. “And I was so sorry,” said Cassy, “for I had always wanted to see a morning-glory, because mother tells how they grew over our porch where we used to live. We would be there now if papa had lived.”

“How long since he died?” Rock asked, sympathetically.

“Six years. I wasn’t three years old, and Jerry was about five. Papa got hurt on the railroad, you know, and he never got well.”

“Yes,” spoke up Jerry. “And mother said some people said she ought to have lots of money from the railroad, because it was their fault, but she tried and they put her off, and she couldn’t afford to have a lawyer, so she just had to give up.”

Rock listened attentively. “I wish she’d come and see papa, he’s a railroad man, and maybe he could tell her what to do.”

“Mother hasn’t any time,” said Cassy, shaking her head gravely. “She makes buttonholes all the time; she has to so as to get us something to eat and to pay the rent, but when we are big we shall not let her do it.”

“Of course not,” said John. “Well, youngsters, I’ve got to go to work. You must come around again some day and tell me how the morning-glories are coming on. There is your geranium, my little lass.”

“And here’s a bunch of violets for your mother,” said Rock. “Tell me your mother’s name and just where you live. Some day I might want to call on you.” He smiled at Cassy as he held out the sweet-smelling violets, and the children, as happy as lords, went off, Jerry carrying his own and Cassy’s books and the little girl holding her geranium carefully with one hand, and in the other bearing the violets which she sniffed frequently as she went along.

WHERE IS JERRY?

CHAPTER III

Carrying her plant in triumph, Cassy appeared before her mother.

“See, see,” she cried out, “just see! Isn’t it lovely? And look at these violets. Oh, mother, we’ve had the loveliest time, and Jerry has some morning-glory seeds in his pocket. You don’t know all we’ve been doing. Were you worried that we didn’t come home to dinner? Did you think we were kept in?”

“No, for I thought it probable that the charms of that garden would prove too much for you, yet I thought I should have two half-starved children to come home to supper.”

“But we’re not half-starved. We had—oh, mother, it’s just like a story. Tell her about it, Jerry, while I put my flower in the window, and give the violets a drink of water.” She set the flower-pot carefully on the sill, and then stood off to see the effect. Truly the gay pink blossom did brighten up the bare room, while the scent of the violets filled the air. “I feel so rich,” said Cassy. “I never had such a lovely day.”

“And how about the lessons?” asked Mrs. Law.

Cassy looked a little crestfallen.

“The lessons weren’t quite as good as they are sometimes. You see,” she came close to her mother and fumbled uneasily with the hem of her apron. “You see, mother, I couldn’t help thinking about the garden all the time, and I came near being kept in ’cause I didn’t pay attention. Wouldn’t that have been dreadful?”

“It would have been pretty bad, for it has never happened to you, and I would have been very sorry to have had you come home with such a report.”

“But I remembered just in time, and I did pay attention the rest of the day. Are you tired, you poor mother, sitting here stitching, stitching all day long? If I could only have brought you a piece of that pie.”

“Do you think that would have rested me? I am not so very tired, for this is only Monday, you know.”

“Oh, Jerry,” Cassy turned to her brother, “we forgot to tell her what the nice boy said. Is he a boy or a young gentleman?”

“Oh, he’s just a boy,” said Jerry grandly, with the judgment of his superior years.

“His name is Rock, Rock Hardy, but his mother’s name is Dallas. That is the old Dallas place, you know, where the garden is, and Rock—Mr. Rock?” She looked inquiringly at Jerry who answered, “No, just Rock; he told me to call him that. His real name is Rockwell, but they call him Rock for short.”

“Well then, Rock said that he wished you would come to see his father. He is a railroad man and maybe he could get you that money.”

Mrs. Law shook her head.

“That was very kind, I am sure, but I could not think of troubling a stranger. No doubt the boy might think his father would be interested, but that was only his idea, and I couldn’t think of calling on Mr. Dallas upon such an invitation. I suppose the gentleman is Mr. Dallas, and Rock Hardy is his stepson.”

“Yes, he is, and I think Mr. Dallas must be very nice, for Rock is so fond of him.” Cassy looked disappointed that her mother had not been willing to go right off to see Mr. Dallas. She had dreamed that great things would come of it, and now her hopes were blasted. But it did not take from the memory of the day’s pleasure, and she went about the room, setting the table for supper, and attending to her little duties, singing softly.

There was not much in the room; a few cheap chairs, one a large rocker, a table covered with a red cloth, a kitchen safe and a small cook-stove; the windows were hung with cheap white curtains, but the floor was bare of carpet, though it had been stained. The house was an old one, and was let out in rooms to tenants who could afford only a small rent, consequently the neighborhood was now none of the best. There was an ill smell of cooking in the halls, and the sound of a constant banging of doors, and the shuffle of heavy feet on the bare stairs could always be heard.

The top floor Mrs. Law thought by far the most desirable, although it was the cheapest, and with her children near her, away from the confusion and noise below, she felt that it was as much of a home as she could hope for.

[Illustration: “EVERY NOW AND THEN FLORA WAS CARRIED OVER AND SHOWN THE GERANIUM”]

It was hard to keep sturdy Jerry from mixing with the neighborhood boys, but though he had learned many of their rough ways and much of their speech, he was not without good principles, and was careful not to bring the language of the street into his home. His faults were not such as came from an evil heart, and his love for his mother and sister would cause any one to forgive him many mistakes.

Cassy was such a mother-child that she shrank from the children in the house, and when she was at home from school rarely played with them. She would rather stay with her mother. Her principal playmate was a battered doll, which she had owned since she was a baby. It was the last gift from her father, and she prized it above all her possessions.

The next afternoon she established herself in a corner with her doll, Flora, and carried on a long whispered conversation with her. Every now and then Flora was carried over and shown the geranium, and made to peer into the box which held the morning-glory seeds. At last the daylight waned and Mrs. Law moved nearer the window.

“It’s ’most bedtime, but I’ll tell you a story before you go to bed,” she heard Cassy say to her doll. “Listen, and it will give you something to think about while you are trying to go to sleep. Once there was a little girl ’bout as big as me, and she had a mother and a brother and she hadn’t any money at all, but they all wanted some, so her mother went to see a gentleman who knew where there was lots of railroad money, and he gave a whole lot of it to her mother ’cause her husband had been hurt in a railroad accident, and so the little girl had a whole window full of flowers and violets every day, and chicken sandwiches and apple pie, but she didn’t get a new doll, only a new silk dress for her old one—a blue silk dress just like the sky, and oh yes—they had a nice little house with morning-glories growing all over the porch, and the little girl’s mother didn’t have to make any more buttonholes or sew any more on the sewing-machine; she sat on a velvet chair and ate the chicken sandwiches and apple pie all day.”

At this point Mrs. Law laughed. “Didn’t she get rather tired of that?” she asked.

“Oh, mother, were you listening?”

“I couldn’t very well help hearing.”

“That’s a new story,” said Cassy, gravely undressing her doll. “I’ve never told it to Flora before. It’s not quite a true story, but I wish it was, don’t you?”

“All but the occupation of the little girl’s mother. I think she would get dreadfully tired of sitting on a velvet chair, and of eating sandwiches and pie all day.”

Cassy laughed.

“I don’t believe I’d get tired of them. Come, Flora, you must go to bed. I’ll give you one more sniff of violets before you go.” And after being allowed once more to bury her snub nose in the bunch of violets, Flora was put to bed, her crib being a wooden footstool turned upside down, and her covers being some old bits of cotton cloth.

“Go call Jerry and we’ll have supper,” said Mrs. Law.

Cassy placed the violets carefully in the middle of the table, and leaving her mother to dish up the oat-meal, she went in search of Jerry. Hearing voices in the back yard she first went there, but there was no sign of him, and she went next to the front door, which generally stood wide open. She looked up and down the dingy street, but saw nothing of her brother. She ran down the steps looking to right and left. At the corner she saw Billy Miles with a group of boys.

“Who ye lookin’ fer?” asked Billy.

“I’m looking for Jerry,” Cassy told him. “Have you seen anything of him?”

“I seen him ’bout an hour ago,” he returned, winking at the other boys, who broke out into a loud laugh.

Cassy looked at them sharply.

“You know where he is,” she said positively. “I think you might tell me.”

“I don’t have to,” said Billy teasingly. “Go look for your precious brother if you want him. He’s so stuck up I guess you’ll find him on top of a telegraph pole.”

Another loud laugh followed this witty remark, and Cassy turned away feeling that Jerry was in some place of which the boys knew, and that they had been the means of keeping him there. She well knew that to go home and tell her mother or to get the policeman on the beat to help her would be a sure means of bringing future trouble upon both herself and Jerry, so she determined to hunt for him herself.

She ran down the street calling, “Jerry, Jerry, where are you?” But after making a long search and finding no sign of her brother, she went back home discouraged.

“Jerry isn’t anywhere,” she announced to her mother. “What shall we do?”

“Perhaps he has gone on an errand for some one. He does that sometimes, you know. We will have supper and save his.”

Jerry very often did turn an honest penny by running errands after school hours, and his absence could easily be accounted for on that score, but still Cassy was not satisfied. Somehow the recollection of Billy’s teasing grin remained with her, and she ate her supper very soberly.

“Mother,” she said after she had finished, “do you mind if I go around to the garden and see if Jerry is there? I don’t feel very sure about his going on an errand.”

Her mother smiled.

“Why, my dear, you are not worrying, are you? I think Jerry will be here soon.”

“I know,—but—Billy Miles—I believe he knew where he was—and please, mother——”

“Well dear, if you will hurry right back, you may go. It will soon be dark, and I don’t want my little girl to be out in the streets so late.”

“I’ll come right back,” Cassy promised earnestly; “I will truly, mother.”

“Very well, run along, though I cannot see why you think you will find Jerry there.”

“Maybe Mr. McClure is working late; sometimes he does and Jerry may be helping him.”

“Very well,” her mother repeated, “run along as fast as you can.”

Cassy caught up her hat and hurried off, not stopping to look at or to speak to any one, and was around the corner in a jiffy, reaching the old Dallas place in a very short time. First she stopped a moment before the gate in the wall, thinking she might hear voices, but all was silent.

“I can’t hear even the daffodils ringing their bells,” said the child to herself as she ran around to the other side of the house. Just as she was passing the front door some one called her.

“Miss Morning-Glory, oh, Miss Morning-Glory!” Looking up she saw Rock Hardy standing on the steps. “Where are you going so fast, Cassy?” he asked. “Did you want to see John? He went home an hour ago.”

“Oh, then, Jerry isn’t here,” Cassy exclaimed.

“No, I don’t think so, in fact I know he isn’t, for I have just come from the garden and no one was there.”

Cassy’s face took on a troubled look, and Rock came down the steps looking at her kindly.

“Is Jerry lost?” he asked, smiling. “It seems to me he is rather a big boy to get lost. I reckon he’s man enough to know his way about town.”

“It isn’t that,” said Cassy, “but I’m afraid those boys—Billy Miles, you know, and the rest—I’m afraid they’ve done something to him.”

“What makes you think so?” Rock came nearer. Cassy gave her reasons and Rock listened attentively. “I’ll tell you what we’ll do,” he said; “I’ll go back with you and help you find him. We can stop and tell your mother so she will not mind your being out. I don’t doubt but that the boys only wanted to tease you, and that he really has gone on an errand, but wherever he is we’ll find him.” He took Cassy’s hand in his and she felt great relief of mind. To have such a big boy as champion meant a great deal.

The two traveled along together, Rock looking around him interestedly as they came nearer Cassy’s abode. He wondered why such a very nice little girl should be living in such a dirty street, and he wondered more as they mounted the steps and went from flight to flight.

“It’s at the very top,” Cassy told him, and finally her door was reached and they went in. “This is Rock,” said Cassy to her mother, “and he’s going to find Jerry.” She spoke with confidence.

Rock, seeing the sweet-faced woman who spoke with such a gentle voice, did not wonder that Cassy seemed such a little lady. She looked like her mother and had just such a way of speaking.

“I suppose Jerry hasn’t come yet,” said Rock.

“No,” Mrs. Law replied. “He has been gone a long time for him; he is usually home to supper. I hope nothing has happened; that he——” she looked at Cassy, “that he has not been run over or anything of that kind,” she added, hesitatingly.

“Oh, I don’t believe that,” said Rock in an assured tone. “You know they say ill news flies swiftly, so we’ll think he has gone off some distance and has been detained. Cassy and I will find him. We will inquire around, for some one has seen him go, no doubt.”

“I am very much obliged indeed,” Mrs. Law told him. “I shall feel quite satisfied to have Cassy go if you are with her.” Therefore Rock and Cassy took their departure.

Rock’s first move was to inquire of the big policeman at the corner if he had seen Jerry Law since four o’clock. The policeman looked up and down the street and then at Rock and Cassy.

“Jerry Law, is ut?” he asked. “A small-sized lad ut lives next dhoor to that little haythin Billy Miles? I’ve not seen um. Howld on; I did thin, airly in the afternoon. There was a crowd of bhoys out be Jimmy McGee’s lumber yard, and I belave Jerry was with the lot.”

“Thank you,” said Rock. “You see he hasn’t come home yet, and his sister is worried.”

“He’ll be afther shtayin’ out later whin he’s a bit owlder,” said the policeman with a grin. “He’s not far off, I’m thinkin’. He’ll be playin’ somewhere, you’ll find.”

The children had started off again when the policeman called them back.

“The bhoys were chasin’ a bit of a dog, I moind,” he told them.

“Oh!” exclaimed Cassy, “then Jerry must have tried to get it from them. I know he wouldn’t let any one hurt it if he could help it. Nothing makes him so mad as to see boys hurt poor little cats and dogs; he’ll fight for them when he won’t for anything else.”

Towards the lumber yard they went, and there they stood calling “Jerry, Jerry Law!” They walked along slowly, stopping every little while to listen. At last when they had reached the end of the lumber yard they heard an answer to their call.

“Listen! Listen!” cried Cassy joyfully. “Some one answered.”

“Call again,” said Rock. And Cassy shrilly screamed “Jerry! Jerry!”

“Here I am,” came the reply.

They looked around but could not seem to discover the spot from which the answer came.

“Where are you?” called Rock.

“In the cellar,” was the reply.

“There, there, in that empty house!” Cassy dragged Rock along towards the corner, and crouching down by a little window at the side of the house, she said, “Are you in there, Jerry?”

For answer a face and form appeared at the window, and there was Jerry sure enough.

A NEW ACQUAINTANCE

CHAPTER IV

“Oh, Jerry, Jerry, how did you get in there?” cried Cassy. “Can you get out?”

“They fastened the door. I’ve banged and banged, but I couldn’t budge it. Gee! but I’m glad you came. The door is ’round at the other side.”

Rock was already on his way to it, and after climbing a fence he was able to get it unfastened and to set the prisoner free. Cassy waited impatiently at the gate, till Jerry with a mite of a puppy in his arms, came out. The boy was battered and dirty, and bore the marks of a hard fight.

“Oh, you poor dear,” Cassy exclaimed, “how long have you been in there? Oh, Jerry, you have been fighting.”

“Of course I have,” he said grimly; “I wasn’t going to let a parcel of great big lunks set upon one poor little puppy without trying to take his part.”

“Good for you!” cried Rock, putting his arm across the shoulders of the smaller boy. “Tell us all about it, Jerry.”

“Billy Miles and the other fellows were stoning this poor little chap, and I went for ’em. They chased us into this cellar, and I managed to fasten the door on the inside, for I knew if they once got hold of the dog they would kill it to spite me; so then they fastened the door on the outside and left us there.” Jerry told his story in a few words, stroking the mite of a dog meanwhile.

“How long ago was that?” asked Rock.

“Not long after I came home from school.”

“You’ve had a long wait,” Rock remarked. “I’m glad we found out where to look for you. Now we’ll go along, and I’d like to see those boys bother you.” He threw back his head and there was a resolute look in his eyes.

“They’d better not try it,” said Jerry, looking up confidently into the bigger boy’s face.

“Do let me carry the puppy,” begged Cassy. But the puppy, now that it had escaped from its safe retreat, felt itself to be in the land of the Philistines, and had confidence in no one but the sharer of its imprisonment; therefore Jerry carefully hid it under his jacket, and they traveled back to where Mrs. Law was anxiously watching for them. At Rock’s suggestion they stopped to get some milk for the puppy, and then Rock left them safe at their own door.

“You will let us keep the puppy, won’t you, mother?” the children begged.

“If it should get away, and anything should happen to it, you would grieve for it, and you know those spiteful boys would be only too glad to hurt it,” she told them.

Cassy burst into tears; the evening’s excitement and anxiety had been too much for her.

“How can they be so cruel!” she cried. “What harm could a poor little dog do? If they would only kill it outright it wouldn’t be so bad, but to stone it and make it suffer for days is so dreadfully, dreadfully wicked.” She crouched down on the floor where the little dog was hungrily lapping its milk, and her tears fell on the rough gray coat, as she tenderly stroked the little creature.

The picture she drew was too much for Mrs. Law’s tender heart, and she said: “You may keep it for a few days anyhow, and in the meantime perhaps we will be able to find a better home for it.”

Cassy smiled through her tears, but she sat looking very soberly at the small animal.

“I saw some wicked, wicked girls, one day, mother,” she said presently; “girls, not boys,—and they were swinging a poor little kitten around by one paw, and then they would let it go up into the air and fall down on the ground as if it had no feeling, but some lady came along and made them stop, and she carried the kitten away with her. I was so glad she did, and I wanted, oh I did want to take those girls up to some high place and do the same thing to them as they were doing to the kitten; I wonder how they would like it.” There was a vindictive expression on Cassy’s face that her mother did not like to see.

“Why Cassy,” she said gently, “you must not be so spiteful; that would be doing as wickedly as the girls did, and you would know better, whereas they probably did not think they were hurting the kitten; I doubt if any one had ever told them that it would hurt a cat to do that to it, though it would not hurt a doll.”

“I can’t help it,” persisted Cassy; “they were wicked and they ought to be punished, and I would like to be the one to do it.” She now had the puppy in her lap, the comfort of which seemed to appeal to the little thing, for it snuggled down comfortably. “It is so cunning,” Cassy murmured in a soft voice very unlike the one she had just used. “See, Jerry, it is going to sleep.”

If anything, Jerry was the more interested of the two, for had he not snatched him from a dreadful fate? And the two children vied with each other in paying this new member of the family such attentions as they could.

With her flowers and the puppy Cassy was very happy for the next few days. The existence of that garden, too, which she might expect once in a while to visit, was another source of delight, and though she generally had kept more or less aloof from her school-fellows, she now did so more than ever. Very often they would pass her sitting in some corner at recess, and she would hear them say: “There’s Miss Oddity. I wonder what she’s mooning about now.”

“Snakes or spiders, or some old thing like that,” she once heard the answer come, and she smiled to herself. They were never able to get over the fact that she was not afraid of mice, and that once she had spent the whole of her recess watching a colony of ants.

“What do you suppose Cassy Law has been doing?” one of the girls said to the teacher who had come out to watch the class as they returned to the school-room.

“What?” asked Miss Adams sharply, keen to discover some misdemeanor.

“She’s been playing with ants; she won’t play with us.” And the girls around giggled.

“She is an oddity,” Miss Adams had replied, and the girls, catching the name, thereafter applied it to Cassy, so that now she was always Miss Oddity. A girl who preferred to play with ants to romping with her schoolmates was something unusual, so they avoided her, and she, feeling that they had little in common, withdrew more and more. Although she longed for a real playmate, a girl after her own heart, none came her way, and finally she invented one.

It was a great day when her imagination created Miss Morning-Glory. It was the day when her first morning-glory seed popped a tiny green head above the earth, and in her exuberance of joy over the fact, Cassy started to school with a great longing for some girl companion who could understand her love for green growing things and for helpless little creatures. Then came the thought, “I’ll make believe a friend, and I’ll call her Miss Morning-Glory,” and forthwith she started up a conversation with this imaginary comrade, to whom she was talking animatedly when several of the schoolgirls passed her. They stopped, stared, and nudged each other.

“She’s talking to herself,” they whispered. “I believe she’s crazy.” But Cassy’s lessons that day were those of a very intelligent little girl, and the others were puzzled.

After this Cassy was not lonely. What could not this new friend say and do? there were no limits to her possibilities. She was always ready when Cassy wanted her. She never quarreled, never objected to any play that Cassy might suggest, and moreover loved and understood all about animals and growing plants.

On the day of the discovery of this new friend Cassy came home with such a happy face that her mother asked: “What has happened, daughter? You look greatly pleased.”

Cassy went over to the window-sill and peered into the box of brown earth where several new blades of green were springing.

“They are coming! they are coming!” she cried.

Her mother smiled, and then she sighed. “How you do love such things, Cassy,” she said. “I wish you could live in the country.”

Cassy came over and put her arms around her mother’s neck. “I don’t mind so much now that I can go to the beautiful Dallas place, and now that I have Miss Morning-Glory. Oh, mother, it is so lovely to have her.”

“Her? You mean them, don’t you? I think there will be many Miss Morning-Glories in that box before very long.”

“No, I mean her.” She spoke a little shyly. “She is a new friend. I made her up like—like a story, you know, and she likes all the things I do. She is here now; she walked home with me, and she plays with me at recess. She likes to watch the ants, and the flies, and the bees.”

Her mother looked a little startled. She was not quite sure if this imaginary friend was a wise companion for her little girl, yet since she did exist in Cassy’s world of fancy, there was nothing to do but let her stay there.

“I call her Miss Morning-Glory,” Cassy went on. “She wears the same colored dresses the morning-glories do. To-day she has on a pink one.”

“What does she look like?” inquired Mrs. Law, thinking it would be best not to discourage the confidence.

“She isn’t a bit like me,” Cassy replied. “She has lovely blue eyes and pink cheeks and golden hair all in curls, not tight curls, but the kind that angels have.”

“What do you know about angels’ curls?” her mother asked, laughing.

“Why, the pictures tell,” Cassy returned, surprised at such a question. “You know the Christmas card I have with the angel on it; that kind of curls I mean.”

“And what is Miss Morning-Glory doing now?”

Cassy glanced quickly across the room. “She is over there holding the puppy. She says she wishes you would let us keep him and name him——” she paused a minute, “name him Ragged Robin.”

Mrs. Law laughed again. “That’s a funny name for a dog.”

“Well, you know, they are shaggy like he is. Mr. McClure showed me a picture of them, and doggie is a kind of blue.”

“So he is. I think he is what they call a Skye-terrier, but I wouldn’t name him if I were you, for we have found a good home for him in the country.”

“Oh!” The tears sprang to Cassy’s eyes. “Jerry will be so sorry; he loves the dear little fellow.”

“I know he does, and I wish we could keep him, but you know, dear, the little milk he drinks is more than we can afford, and as he gets bigger he will require more.”

“Yes, I know,” said Cassy, faintly.

“Wouldn’t you rather he should go where he can have all he wants to eat and drink, and where he will have plenty of room to run about?”

Cassy gave a long sigh. “Who is going to take him, mother?”

“The milkman. You know he brings his milk direct from his farm, and he is a kind man who has children of his own, and I know they will be good to the little doggie. I think it would be better that he should go before you and Jerry become too fond of him, for you see he has only been with you such a short time that you will not miss him as you would if you waited longer.”

“I know,” Cassy repeated, but the tears still stood in her eyes.

She had hoped that the puppy might be allowed to stay altogether, although from the first her mother had declared that it could not. Jerry was scarcely less distressed than Cassy when he was told that the puppy must go. He did not say much, but he carried the little fellow off to his room and when they came out again Jerry’s eyes were very red, and if any one had taken the trouble to feel the top of the puppy’s head he would have discovered a wet spot upon it, caused by the tears that Jerry had shed.

“If we only lived in the country,” said the boy, “we might keep him, but if anything was going to happen to him on account of our keeping him I would rather have him go and be safe. He won’t get any more tin cans tied to his tail, I’ll bet.”

Cassy nodded emphatically.

“Yes, I’m glad, too, for him, but I’m dreadful sorry for us.”

“I declare,” said Mrs. Law, “I have been so taken up with the thought of the puppy that I nearly forgot to tell you something very pleasant. Who do you think was here this morning?”

“I can’t guess. The rag man? Did you sell the rags? Then we will have something good for supper,” for the visit of the rag man always meant an extra treat, a very modest one, to be sure, but still one that the children looked forward to.

“No, it wasn’t the rag man; it was some one much nicer, and he brought an invitation for you.”

“For me?” Cassy’s eyes opened wide.

“Yes, an invitation to spend the day on Saturday.”

“Oh, mother, tell me where. Hurry, hurry and tell me.”

“At Mr. Dallas’s.”

“Oh! oh! a whole day in that lovely place! Was it Mr. McClure?”

“No, it was Rock Hardy. A little girl is to be there for a few days, and Mrs. Dallas thought it would be nice for some one to come and play with her.”

“And they asked me. Oh, how perfectly fine. I hope she is nice and friendly and isn’t stuck up.”

“If she is like Rock Hardy I don’t think you have anything to fear.”

“No, indeed, and did you say I could go mother?”

“Yes.”

“I wish Jerry could go, too.”

“Jerry is going in the afternoon.”

Cassy clapped her hands. “Good! I am so glad. I wish he would come back so we could tell him,” for after his farewell to the puppy, Jerry had not seen fit to remain within sight and hearing of him. “I don’t feel so bad about losing the dear doggie now,” Cassy went on to say. “I must tell Miss Morning-Glory about it!”

She had not told her brother about this new friend, for Jerry was of too practical a turn to appreciate the fancy, and Cassy had asked her mother not to tell him. “You understand, mother,” she said, “’cause mothers always can understand better than boys, and I don’t want Jerry to laugh at me. Do you know,” she told her mother, “that it was Rock Hardy who made me think of that name; he called me by it.”

“Did he? I suppose Miss Morning-Glory will not go with you on Saturday.”

“I don’t believe she will want to,” returned Cassy, easily. “She wouldn’t go without being invited,” which adjusted the matter very satisfactorily.

“Did Rock say what was the name of the little girl?” Cassy asked.

“Her name is Eleanor Dallas,” Mrs. Law told her; “she is Mrs. Dallas’s niece.”

“I hope she is as nice as Rock,” said Cassy, a little uneasily.

THE VISIT

CHAPTER V

“She is such a real little lady,” Rock had told his mother, when speaking of Cassy. “Indeed,” he added, “they are all of them much too good to be living in that dirty, noisy street. I wish there was some way to get them away from there, but I think Mrs. Law is very proud and it wouldn’t do to seem to patronize them. I wish you’d think about it, and see if you can’t get up some nice plan to put them where they belong.”

So Mrs. Dallas had put on her thinking cap, and when little Eleanor Dallas came to spend Easter at her uncle’s house, Mrs. Dallas said to Rock: “How would it do to ask your little friend Cassy Law, to come and play with Eleanor? If she is as well-behaved as you say, I should think we might ask her. You know what a good-hearted child Eleanor is and I am sure she will like to have a little girl to spend the day with her. You see her Cousin Florence is still in Florida with her parents and Eleanor will not have any playmate but you.”

“I think it would be a jolly plan,” Rock agreed, “and do you mind if Jerry comes too? He’s a nice little chap; you remember I told you about that affair with the little dog.”

“I see no objection to his coming, but I think we’ll have him come in the afternoon, but Cassy might spend the day and there will be a good chance to get acquainted with her.” And that was how Cassy came to be asked.

The prospect of this visit did much towards comforting the children after the milkman had borne away the little dog, and they made it their chief subject of conversation. They hoped it would be a pleasant day, that the little girl would be just like Rock, that John McClure would not be too busy, and that they would be allowed to play in the garden.

“Shall I wear my best frock?” Cassy asked her mother one of the first things.

“Yes, you will have to; it is growing too small for you anyhow.” Mrs. Law sighed. “You’d better bring it to me and let me see if there is anything to be done to it.”

Cassy obeyed. Her plaid frock was the best she had; it was not of very good material, but it was simply made, and so did not look as badly as it would have done if it had been fussy and showy. It was rather short in the sleeves and waist as well as in the skirt, and after looking it over Mrs. Law said, “If I had time, I might be able to alter it, but I am afraid you will have to wear it as it is this time, for I have all I can do to get this work done by Saturday.”

“I will help you all I can,” said Cassy wistfully.

“I know you will, dear child, but you cannot sew for me, and there are things beyond your little strength which only I can do, and on Saturday morning Jerry must be at the market, for we can’t afford to let that go. Hang up the dress again.”

Cassy did as she was told, yet she did wish that she had a new frock for this unusual occasion. She wondered if the little girl she was going to see would be very finely dressed, and she found as the time approached that she rather dreaded the visit. But for the fact that she knew and liked Rock and John McClure, she would almost have preferred to stay at home with Flora and Miss Morning-Glory; and when at last she did set out it was with many misgivings.

She was very conscious of the shortness of her sleeves, and the shabbiness of her shoes, though Jerry had blackened up these latter to the best of his ability, and they both agreed that the little cracks in the sides did not show so very much.

The little girl’s heart was beating very fast as she approached the old Dallas place. Was she to go up the front steps and ring the bell, or was she to go around to the side gate and enter that way? She had not thought to ask, and not to do the proper thing would be dreadful.

Finally, after a thoughtful pause, she slowly ascended the steps. If she were going to see a little girl whose uncle’s house this was, she must surely enter as did other visitors, her judgment very wisely told her. She was spared any further confusion, for the door had hardly been opened by the neat maid when Rock appeared, saying: “We’ve been watching for you. Eleanor hoped you’d come early. Come right in. Here she is, Eleanor.” And then Rock led her into a room furnished in rich warm colors, and with bookcases all around the walls.

From the depths of a big chair sprang a little girl who looked, as Cassy afterwards told her mother, exactly like Miss Morning-Glory; blue eyes, pink cheeks, and angel curls were all hers.

“I’m so glad to see you,” said Eleanor sweetly. “Will you go up-stairs and take off your hat, or will you take it off here?”

“Oh, it doesn’t matter,” said Cassy bashfully. Her hat seemed such a very, very insignificant thing beside all this grandeur, but she took it off and held it in her lap.

Eleanor gently took it from her.

“I will hang it up here in the hall,” she said, “and you will know where it is when you want it.”

This done the two little girls sat looking at each other, feeling rather embarrassed. Eleanor was older and taller than Cassy; moreover as hostess she felt it her duty to begin the talking, and she ventured the first remark.

“It is such a pleasant spring day. We were afraid that it might rain and that then you wouldn’t come.”

Cassy felt pleased, but did not know exactly what to say in reply.

“Are you the only girl?” Eleanor asked.

“Yes,” Cassy replied; “there are only Jerry and me.”

“I am the only one,” Eleanor told her. “Don’t you wish you had a sister? I often do.”

“Yes, so do I,” Cassy answered. She would like to have told Eleanor of the new friend of her fancy, Miss Morning-Glory, but she did not feel well enough acquainted yet, and for a little while the two children sat looking at each other wondering what to say next. Then Rock came in.

“How is the puppy?” he asked.

“Oh, didn’t you know? He has gone to live with the milkman,” Cassy told him. “Mother thought he would be so much better off there. He lives in the country, you know, and he said Ragged Robin was a real nice little fellow, and he’d be glad to have him, but we were awfully sorry to let him go.”

“Is that the little dog you were telling me about?” asked Eleanor, turning to Rock.

“Yes, you know, Jerry saved him from that pack of boys,” he made answer. “Why don’t you take Cassy up-stairs to the sitting-room, Eleanor? It is lots more cheerful up there; or maybe she’d rather go into the garden, she’s such a lover of flowers.”

“We might go up-stairs and see Aunt Dora first,” said Eleanor, “and go to the garden after a while. Don’t you think so, Cassy?”

Cassy agreed, although in her secret heart she preferred the garden first, last, and always. Then up-stairs they went to a bright sunny room which Cassy thought the prettiest she had ever seen.

There was a big table, covered with magazines, in the middle of the floor; the window held flowering plants; a number of comfortable chairs and a wide, soft lounge looked as if they were meant for every-day use, while the room had just enough pretty trifles in it to make it look well. The pictures on the walls were a few water-colors, flower pieces and landscapes; while the walls themselves were a soft green with a border of trailing roses. Sitting by the window was a pretty woman, as charming as the room itself.

“Aunt Dora,” said Eleanor, “this is Cassy Law.”

Mrs. Dallas held out her hand.

“I am so glad you could come, Cassy,” she said. “I know Eleanor and you will enjoy playing together. What do you say to having this room to play in this morning? You are going to have luncheon in the garden, or at least Rock has a little scheme that he and John are carrying out, and unless you would specially like to play there, I have my suspicions that they would rather you would keep out of the way this morning, and let them give you a surprise. You can have the whole afternoon there, you know.”

“Oh, do let it be a surprise,” exclaimed Eleanor. “I love surprises. Don’t you, Cassy?”

“Sometimes,” she replied. She felt rather shy as yet, and stood somewhat in awe of this pretty lady in her dainty morning gown.

“I am going to lend Cassy the dolls to play with,” said Mrs. Dallas to Eleanor, “Rock’s and mine, you know; and you will have your precious Rubina, so you will both be provided.” She left the room for a moment and returned bringing a doll dressed in boy’s clothes and another in girl’s clothes; the latter was quite an old-fashioned one.

“These are Marcus Delaplaine and Flora McFlimsey,” said Mrs. Dallas. “They are both Rock’s now, although Flora used to be mine when I was a little girl, so naturally she is much older than Marcus. Rock was always fonder of his own doll when he was a little fellow. He used to say he felt more at home with him. You know where the piece bag is, Eleanor, and if you want to make doll’s clothes you can help yourselves. You don’t have to call the doll Flora if you’d rather name her something else,” she said, smiling down at Cassy, and holding the doll of her childish days affectionately.

“Oh, but I would like to,” Cassy replied. “My doll is named Flora.”

“Is she? then it will seem quite natural to you.” She smiled again and nodding to the two girls, she left them together in the pleasant room. It was not long before they were playing like old friends. Indeed before the morning was over Cassy felt so at home with Eleanor that she told her all about Miss Morning-Glory, and had confessed her discomfort at having to wear a frock she had so nearly outgrown.

Eleanor comforted her upon this last score.

“I am sure it is a real pretty plaid,” she said, “and the warm weather is coming when you won’t have to wear it.” Nevertheless, Cassy knew that she had nothing else so good, and that it would be some time before she could lay this aside. Eleanor was quite taken with the idea of Cassy’s imaginary friend, and suggested that she should make a third in their plays. “It is just as easy to make believe that she is here as to make believe that the dolls can talk,” she declared. “What does she look like?”

“She looks just like you,” Cassy told her a little timidly.

“Oh, then, I’ll be Miss Morning-Glory,” declared Eleanor. “Would you like that?”

Cassy’s eyes showed her pleasure, as she nodded “Yes.”

“Then you won’t feel as if I were a stranger at all, and you can talk to me just as you do to her,” Eleanor went on to say.

This did place Cassy upon easier terms with her new friend, and if Eleanor was sometimes surprised by Cassy’s odd remarks, she was none the less interested in the little girl, though she did not wonder that Cassy’s schoolmates called her Miss Oddity. A little girl who felt entirely at home with spiders, who thought daddy-long-legs fascinating, and who would make such remarks as: “You remember the dear little inching-worm I had last summer, Miss Morning-Glory. I always feel so sorry to think I shall never see it again,” was a queer person surely.

About one o’clock Rock appeared.

“What time will Jerry be here?” he asked Cassy.

“What time is it?”

“One o’clock.”

“Oh, then he can’t be long, for he is generally at home by half-past twelve, at the latest, on Saturdays.”

“Are you all ready for us, Rock?” asked Eleanor. “I am just wild to see what you have been doing.”

Rock smiled. “You will see very soon.”

“Are we going to eat luncheon out of doors?”

“Not exactly.”

“Oh dear! I wish Jerry would come.” Eleanor could not curb her impatience.

“There he is now,” cried Rock. “Come, girls.” And the three rushed down-stairs and into the garden to meet Jerry, who was standing with John McClure waiting for them.

“You want to see what we have been doing, don’t you, Miss Eleanor?” said John, smiling at Eleanor’s eagerness. “Well, come along.” And he led the way down to the foot of the garden where stood a small brick building that was used in winter for the storage of flower-pots, bulbs and such like things.

[Illustration: “THEY PLAYED ALL SORTS OF GAMES”]

As John opened the door the children exclaimed, “Oh, how fine!” for it was like a fairy bower. Along the shelves at each side were ranged flowering plants, and pots of trailing vines. On the floor reaching up to the shelves were boxes of blooming shrubs and palms; two canary birds, in their cages swung in the windows, were singing blithely. In the middle of the floor a table was spread; a centerpiece of ferns and pansies ornamented it, and at each one’s place was a little bunch of sweet violets tied with green and purple ribbons. A pretty basket at each end of the table was tied with the same colors; one basket was filled with sticks of chocolate tied with the lilac and green, and the other held delicate green and purple candies.

“It is just lovely, Rock!” cried Eleanor. “Did you do it all yourself? I think it is lovely, and—oh, yes, I see, to-morrow will be Easter, and that is why you can use all the flowers and plants before they are sent to the church.”

The luncheon that was served, though not a very elaborate one, seemed so to Cassy and Jerry; they felt as if suddenly transported to an Arabian Night’s entertainment, and they looked across the table at each other with smiling eyes.

When the luncheon was over they played all sorts of games, up and down the garden walks and in among the trees and shrubbery. The day would have been one full of content, without a cloud, but for a single accident.

The two girls were hiding in the tool-house, when Eleanor caught sight of a chrysalis swinging from above them.

“Oh,” she cried, “I do believe that is a fine chrysalis of some kind, a rare moth or butterfly. I am going to get it, and see what it will turn out.” She clambered upon some boards to reach the prize, Cassy deeply interested watching her, when suddenly her foot slipped and she knocked from a lower shelf a can of green paint which went down splash upon the floor, spattering Cassy from head to foot.

Cassy was overwhelmed, for poor as the dress was and half ashamed of it as she had been, nevertheless it was the best she had, and her eyes filled with tears. Eleanor, as distressed as her visitor, was at her side in an instant.

“Oh, what have I done? What have I done?” she cried. “Oh, dear, oh, dear! I am afraid it won’t come out. Let us go to Aunt Dora; she will know what to do.” She caught Cassy by the hand and sped with her into the house, calling “Aunt Dora, Aunt Dora, do come and help us! It was all my fault. I have ruined Cassy’s dress.”

Mrs. Dallas appeared at the door of the bathroom where Eleanor had gone with Cassy to try the effect of hot water.

“You didn’t mean to,” put in Cassy hastily.

“No, of course not. My foot slipped, Aunt Dora. I was climbing up for a chrysalis that was in the tool-house, and I knocked the can from the shelf.”

“Cassy had better take her frock off,” said Mrs. Dallas, “and I will see what benzine will do. I am afraid it will not take it out altogether, and that it will leave a stain, but we will try it. Call Martha, Eleanor, and we will do our best with it.”

Much abashed Cassy removed her frock and after some time the paint was taken out as far as possible, but it did leave a stain, and where the spots were rubbed the goods was roughened and unsightly. Cassy’s stockings and shoes, too, were spattered, but the latter were easily cleaned, and Eleanor furnished her with a pair of clean stockings, so this much was readily settled. The frock was another matter, and poor Cassy had visions of staying at home from church, from Sunday-school, and upon all sorts of occasions that required something beside the faded, patched, every-day frock which she wore to school. She could hardly keep back her tears when Mrs. Dallas and Eleanor left her in the latter’s room while they went off to air the unfortunate frock.

PLEASANT DREAMS

CHAPTER VI

After a little while Eleanor returned, went to the closet in her room and hung two or three of her own frocks over her arm; then she went out again and presently Mrs. Dallas came in alone carrying a pretty blue serge suit over her arm.

“Cassy, dear,” she said, “will you try this on?”

Cassy shrank back a little, but Mrs. Dallas smiled and said, coaxingly: “Please, dear,” and Cassy slipped her arms into the sleeves. “It is a little large,” Mrs. Dallas decided, “but not so very much, and it will take no time to alter it; I will have Martha do it at once. Eleanor feels so badly about having spoiled your frock, and I know her mother would wish that she should in some way make good the loss. Please don’t mind taking this; it is one that Eleanor has almost outgrown, and it is only a little long in the sleeves and skirt for you. I will have Martha alter it before you go home, for we would both feel so badly to have your best frock spoiled, and to-morrow being Sunday how could you get another at such short notice?”

She spoke as if Cassy’s were much the better frock and the little girl was grateful, though she said earnestly: “It is much nicer than mine, Mrs. Dallas.”