Read and listen to the book A. L. O. E.'s picture story book. by A. L. O. E..

Audiobook: A. L. O. E.'s picture story book. by A. L. O. E.

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A. L. O. E.'S PICTURE STORY BOOK. ***

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

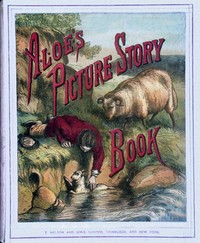

[Illustration]

A. L. O. E.'s

PICTURE STORY BOOK.

LONDON:

T. NELSON AND SONS, PATERNOSTER ROW; EDINBURGH; AND NEW YORK.

1871.

PREFACE.

A PORTION of the Stories in this Volume have appeared in the "Children's Paper," but the greater number have never before been published. A. L. O. E., in sending forth this little Work, feels something like a labourer who, when wearied by heavier work, finds that he can yet tell stories on a winter's evening to the little ones gathering around his chair, or seated on his knee. There is something refreshing to the spirit in the atmosphere of childhood, and an Authoress may feel its influence even in writing for children. Especially is this the case if her aim, in entering nursery or playroom, be to try to make their young inmates more happy, because more loving and good.

A. L. O. E.

CONTENTS.

I. "THE HYMN MY MOTHER TAUGHT ME"

II. THE BEAR

III. THE TIGER-CUB

IV. NOT ONE TOO MANY

V. THE IRON RING

VI. THE ILL WIND

VII. THE TWO PETS

VIII. THE BOY AND THE BIRD'S NEST

IX. THE ENGLISH GIRL AND HER AYAH

X. I'LL NOT LET YOU GO

PART I.

PART II.

PART III.

XI. THE WHITE DOVE

A. L. O. E.'s PICTURE STORY BOOK.

I. "THE HYMN MY MOTHER TAUGHT ME."

"GET away with ye, will ye, Ben Madden! I don't want you a-sneaking about my stall to see what you can be laying your fingers on!" exclaimed Betty Wiggins, the cross old dame who sold biscuits and cakes at the corner of High Street.

The poor orphan boy thus rudely addressed slunk back a pace or two from the tempting stall. His young heart was burning with anger, and indignant tears rose into his eyes.

"I never in my life took what did not belong to me," muttered Ben; "my poor mother taught me something better than that."

Betty Wiggins might have given a kind word to the lonely child, if she had given no more. Ben Madden had lately lost his mother, a poor industrious widow, who had worked as long as her fingers could work to support herself and her orphan boy. Alice Madden had died in peace and faith, commending her child to the care of Him who hath said, "I will never leave thee, nor forsake thee."

Poor Ben seemed to have a hard life struggle before him. He had no relative living but a sailor uncle, who might, for aught that he knew, be now on the other side of the world. There was none to care whether the orphan slept under a roof or an archway, whether he fed or whether he starved. Betty, who had known his mother for years, might have spared him one of those biscuits, and never have missed it amongst so many; so thought Ben, who, since rising at daybreak, had not tasted a morsel of food.

As Ben stood leaning against an area railing, looking wistfully at the piles of cakes and gingerbread nuts, a light cart, in which was seated a reckless young driver urging on an excited horse, was whisked round the corner of High Street with such careless speed, that it knocked over the stall and threw its contents on the pavement. What a scatter was there of tartlets and cakes, bits of toffee and rock, biscuits, bull's eyes, almonds and buns, and sticks of bright barley sugar! Had the stall-woman been any other than cross Betty Wiggins, Ben would have run forward to help her to pick up her goods, which were rolling about in every direction. But a feeling of resentment filled the soul of the boy; he was not sorry for Betty's disaster.

"She bade me keep off," thought the child, "and I will; she would not trust me to pick up her biscuits."

Ben would not go to the cakes, but one of the cakes came to him. A beautiful pink one, studded with almonds, and frosted with sugar, rolled close up to his feet. Betty did not mark this, for with clenched hand and flashing eyes she was pouring a torrent of abuse after the careless driver whose cart had done the mischief, which the youth would not stop to repair. Ben saw the cake—the delicious pink cake—what a temptation to a half famished boy! Forgetful of his own words so lately uttered, in a moment the child caught it up, and hurried away down the street; leaving Betty to abuse the driver, set up the stall, and recover such of her dainties as had not been smashed on the pavement.

Before Ben had walked many steps, he had eagerly swallowed the cake; having once tasted its sweetness, he felt as if nothing could stop him from eating the whole. Ben had committed his first theft, he had forgotten the words of his mother, he had broken the law of his God. Let none of my readers deem his fault a small one, or think that little harm could come from a hungry boy's eating a single cake that had rolled to his feet. Ben's enjoyment was quickly over; what had pleased his taste had but whetted his hunger, and it seemed as if with that stolen morsel evil had entered into the boy.

Every time that we yield to temptation, we have less power to resist it in future. Many sinful thoughts came into the mind of Ben as he lounged through the streets. Never before had he so envied the rich, those who could feast every day upon dainties. With a careless eye, he gazed into shops filled with good things which he could not buy. With a repining, discontented spirit, he thought of his own hard lot. Why had his mother been taken from him? Why had he been left to sorrow and want?

Then, in this dangerous state of mind, Ben began to consider how he could find means of supplying his need. He did not think now of prayer; he did not think of asking his heavenly Father to open some course before him by which he might honestly earn his bread. Ben remembered how that sharp lad, Dennis O'Wiley, had told him that he knew ways and means by which a lad could push himself on in the world. When Ben had repeated these words to his mother, she had warned him against Dennis O'Wiley; she had said that he feared neither God nor man, and would end his days in a prison. Ben had resolved, in obedience to his parent, never to keep company with the lad; but, since stealing that pink sugared cake, Ben found his resolution beginning to waver. He could see no great harm in Dennis, as good-natured a fellow as ever was born; why should he not ask a bit of advice from a chap who seemed always to find out some way of getting whatever he wanted?

Alas, poor Ben! He had been like one standing at a spot where two roads branch off: the strait one leading to life, the broad one leading to destruction—his first theft was like his first step in the fatal downward road. But for a little incident which I am going to relate, the widow's son might have gone from evil to evil, from sinful thoughts to wicked deeds, till his heart had grown hard, and his conscience dead, and he had led a life of guilt and of shame, to close in misery and ruin.

As Ben was sauntering down a street, half resolved to seek Dennis O'Wiley, his ear caught the sound of music. It came from an open door, leading into an infant school. Ben, who dearly loved music, drew near and listened to the childish voices singing a well-known hymn. Very heavy grew the heart of the boy, and his eyes were dimmed with tears, for he heard the familiar words—

"Oh, that will be joyful When we meet to part no more!"

Ben's lips quivered as he murmured to himself, "That is the hymn my mother taught me."

What seeming trifles will sometimes change the whole current of our thoughts! The sound of that music brought vividly before the mind of poor Ben his mother's face as she lay on her sick-bed: the touch of her hand, her fond look of love, her dying words of advice to her son. It was as if she had come back to earth to stop her poor boy on his downward way. His thoughts were recalled to God and heaven, to that bright home to which he felt that his mother had gone, and where he hoped one day to join her—the blessed mansions prepared by the Saviour for those who love and obey Him.

"Holy children will be there Who have sought the Lord by prayer."

Ben turned away with almost a bursting heart. Heaven is not for the unholy, the disobedient, the covetous, for those who take what is not their own! If he went on in the fatal course on which he had entered that day, he would never again meet his mother, he would never be "joyful" in heaven! Was it too late to turn back? Might he not ask God's forgiveness, and pray for grace to lead a new life?

"Yes," thought the penitent child, "I will never forget my mother's wishes, I will follow my mother's ways! With the very first money that I get, I will pay for the cake that I stole."

The strength of Ben's resolution was very soon put to the test. Scarcely had he made this silent promise, when a carriage with a lady inside it was driven up to the school, and as there was no footman with it, and the coachman could not leave the box, Ben ran forward to open the door, and guard the lady's dress from the wheel. The lady smiled kindly on the child, and taking a penny from her bag, dropped it into his hand.

Here was a penny honestly earned; a penny that would buy two stale rolls to satisfy the hunger of Ben. Could it be wrong thus to spend it! Had he received it one hour before, Ben would have run to a baker's shop, and laid out the money in bread; but conscience now whispered to Ben that he had a debt to discharge, that that penny by right was Betty's, and that his first duty was to pay for the cake which he had wrongfully taken.

"But I'm so hungry!" thought Ben, as he looked on the copper in his hand. "I will buy what I need with this penny, and pay my debt with the next. But yet—" Thus went on the struggle between self-will and conscience—"my mother taught me that to put off doing what is right, is actually doing what is wrong. Often have I heard her say, 'When conscience points out a difficult duty, don't wait in hopes that it will grow easy.'"

Ben turned in the direction of High Street, but before two steps on his way, pride offered another temptation. "I can't bear to go up to Betty," thought Ben, "and tell her that I stole her cake!" He stopped short, as the thought crossed his mind. "But can't I walk by her stall, and just drop the penny on it as I pass, and say nothing to bring myself shame!"

A little reflection showed Ben that this could not be done. "She'd be crying out again, 'Get away with ye;' she'd think I was fingering her cakes. Besides—" here conscience spoke strongly once more—"does not the Bible tell us to confess our faults one to another? Is it not the brave, the right way to go straight to the persons we've wronged and tell them we're sorry for the past?"

It was a hard struggle for Ben, and when with a short, silent prayer for help, he walked on again towards High Street, the child was more of a true hero than many who have earned medals and fame. He was conquering Satan, he was conquering self, he was bearing hunger and daring shame, that he might be honest and truthful.

Ben soon came in sight of Betty and her stall; it seemed to the boy that the wrinkled old face looked more cross and peevish than ever. A sailor was standing beside the woman, buying some gingerbread nuts.

"Now or never," thought Ben, who did not trust himself to delay, now that his mind was made up. His face flushed to the roots of his hair with the effort that he was making, the child walked straight up to the stall, laid his penny upon it, and said, "I took one of your cakes to-day—I'm sorry—there is the money for it!"

"Well, Ben Madden!" exclaimed the old woman in surprise, "you're an honester lad than I took you for—you mind what your mother taught you."

"Ben Madden!" cried the sailor, looking hard at the orphan boy. "That's a name I know well. Can this be the son of the sister whom I've not set eyes on these seven long years!"

"His mother was the widow of big Ben the glazier," said Betty, "who died by a fall from a window."

"The very same!" cried the sailor, grasping the hand of his nephew, and giving it a hearty shake. "What a lucky chance that we met! And where's your mother, my boy?"

Tears gushed into poor Ben's eyes, as in a low voice, he answered, "In heaven."

The seaman's rough hearty manner instantly changed; he turned away his head, and was silent for several minutes, as if struggling with feelings to which he was ashamed to give way. Then, laying his brown hand on the shoulder of his nephew, he said in a kindly tone, "So you've neither father nor mother, poor child; you're all alone in the world! I'll be a father to you, for the sake of poor dear Alice."

Fervently did poor little Ben thank God who had thus provided for him a friend when he most needed one, and least expected to find one! With wonder, the orphan silently traced the steps by which his heavenly Father had led him. What a mercy it was that he had passed near the school,—that he had heard the hymn,—that he had resolved to be honest,—and that his resolution had brought him to the cake-woman's stall when the sailor was standing beside it! Had Ben delayed but for ten minutes, he would never have met his uncle! Yes, in future life, the orphan frequently owned that all his earthly comforts had sprung from the decision which he had been strengthened to make when, at the turning-point of his course, he had stood at the door of the infant school, listening with a penitent heart to the hymn which his mother had taught him!

II. THE BEAR.

"HE is just like a bear!" That is a very common expression when we talk of some ill-tempered man or boy, who takes a pleasure in saying rude things, and who seems bent upon making every one near him as uncomfortable as he can.

But we may be unjust even to bears. Could you have gone to wintry Greenland, and seen Mrs. Bruin amidst her family of little white cubs, each scarcely bigger than a rabbit, you would have agreed that a bear can be a kind and tender mother, and provide for her four-footed babies a snug and comfortable home.

You would, indeed, have had some difficulty in finding Bear Hall, or Bear Hole, as we rather should call it. Perhaps in wandering over the dreary snow-covered plains of Greenland, you might have come upon a little hole in the snow, edged with hoar-frost, without ever guessing that the hole was formed by the warm breath of an Arctic bear, or that Mrs. Bruin and her promising family were living in a burrow beneath you. *

* See "Homes without Hands."

How wonderfully does Instinct teach this rough, strange-looking creature to provide for her cubs! The mother bear scrapes and burrows under the snow, till she has formed a small but snug home, where she dwells with her baby-bears during the sharpest cold of an Arctic winter. So wonderfully has Providence cared for the comfort even of wild beasts, that the mother needs no food for three months! She is so fat when she settles down in her under-snow home, that her own plumpness serves her instead of breakfast, dinner, and supper; so that when at last she comes out to break her long fast, she is not starved, but has merely grown thin. I need hardly remind my reader that the Arctic bear is provided by Nature with a thick, warm, close-fitting coat of white fur; and the snow itself, strange as it seems to say so, serves as a blanket to keep the piercing air from her narrow den.

Yes, Mrs. Bruin was a happy mother, though her cell was small to hold her and her children, and the cold above was so terrible that water froze in the dwellings of men even in a room with a fire. Mrs. Bruin found enough of amusement in licking her cubs, which was her fashion of washing, combing, and dressing, and making them look like respectable bears. She let them know that she loved them dearly in that kind of language which little ones, whether they be babies or bear-cubs, so soon understand.

But when March came, Mrs. Bruin began to grow hungry, and think that it was full time to scramble out of her under-snow den, and look out for some fish, or a fat young seal, to eat for her breakfast. The weather was still most fearfully cold, and the red sun seemed to have no power at all, save to light up an endless waste of snow, in which not a tree was to be seen save here and there a stunted fir, half crusted over with ice.

Safe, however, and pretty warm in their shaggy furs, over the dreary wilds walked Mrs. Bruin, and the young bears trotting at her heels. They went along for some time, when they came to a round swelling in the snow; at least so a little hut appeared to the eyes of a bear. Indeed, had our own eyes looked on that snow-covered hillock, we should scarcely at first have guessed that it was a human dwelling.

Perhaps some scent of food came up from the chimney-hole, which made Mrs. Bruin think about breakfast, for she went close up to the hut, then trotted around it—her rough white nose in the air. She then uttered a low short growl, which made her cubs amble up to her side.

Oh, with what terror the sound of that growl filled the heart of poor Anneetah, the Esquimaux woman, who was with her little children crouching together for warmth in that hut!

"Did you hear that noise?" exclaimed Aleekan, the eldest boy, stopping suddenly in the midst of a tale which he had been telling.

"There's a bear outside!" cried all the younger children at once.

Anneetah rose, and hastily strengthened the fastenings of her rude door with a thick piece of rope, while her children breathlessly listened to catch again the sound which had filled them with fear.

"The bear is climbing up outside!" cried little Vraga, clinging in terror to her mother. "I can hear the scraping of its claws!"

There was an anxious pause for several minutes, all listening too intently to break the silence by even a word. Then, to the great alarm of the Esquimaux, the white head of an Arctic bear could be plainly seen, looking down upon them from above. The animal had, after clambering up to the top of the hut, enlarged the hole which had been left in the roof to let out the smoke.

"We're lost!" exclaimed Aneekah.

"O mother, let us pray! Will not God help us?" cried one of the children. *

The prayer could have been but a very short one, but the presence of mind which the mother showed may have been given as the instant answer to it. Aneekah caught up a piece of moss, stuck it on a stick, set it on fire, and held the blazing mass as close as she could to the nose of the bear.

* This incident of the intrusion of the bear, and the exclamation of the child, has been given as a fact.

Now fire was a new thing to Mrs. Bruin, and so was smoke, and if the bear had frightened the Esquimaux, the Esquimaux now frightened the bear. With a snort and a shake of her shaggy fur, the animal drew back her head, and, to the surprise and delight of the trembling family, they soon heard their unwelcome visitor scrambling down faster than she had clambered up. Mrs. Bruin trotted off to seek her breakfast elsewhere; let us hope that she and her cubs found a fine supply of fish frozen in a cleft in some iceberg floating away in the sea. At any rate, they never again were seen near the Esquimaux home.

Do you wonder how the poor Esquimaux child had learned the value of prayer? Would any one go to the dreary wilds of Greenland to carry the blessed gospel to the natives of that desolate shore?

Yes, even to "Greenland's icy mountains" have missionaries gone from brighter, happier lands. There are pastors now labouring amongst the poor Esquimaux, for they know that the soul of each savage is precious. The light of the gospel is shining now in Esquimaux homes, and, amidst all their hardships, sufferings, and dangers, Esquimaux have learned to show pious trust when in peril, and thankfulness after deliverance. It is from the pen of a missionary that we have learned the story which I have just related of the Esquimaux woman and the white bear.

III. THE TIGER-CUB.

"REALLY, Captain Guise, you need trouble yourself no more in the matter; I am quite able to take care of myself!" cried young Cornet Stanley, with a little impatience in his tone.

The speaker was a blue-eyed lad, whose fresh complexion showed that he had not been long in the burning climate of India. Cornet Stanley had indeed but lately left an English home, for he was little more than sixteen years of age. With very anxious feelings, and many tears, had Mrs. Stanley parted with her rosy-checked Norman. "He is so very young," as she said, "to meet all the trials and temptations of an officer's life in India!"

Mrs. Stanley's great comfort was that her Norman would have a tried and steady friend in her cousin, Captain Guise, who would, she felt sure, act a father's part to her light-hearted boy. Young Stanley was appointed to the same regiment as that of the captain; and almost as soon as the cornet had landed in India, he proceeded up country to join it. The season of the year was that which is in India called the cold weather, when many Europeans live in tents, moving from place to place, that they may amuse themselves with hunting and shooting.

Norman Stanley, who had never before chased anything larger than a rabbit, was delighted to make one of a party with two of his brother officers, and enjoy with them for a while a wild, free life in the jungle. There would have been no harm at all in this, had Norman's new companions been sober and steady young men; but Dugsley and Danes were noted as the two wildest officers in the regiment.

Captain Guise was also out in camp, and his tent was pitched not very far from that of his young friend Norman. The captain took a warm interest in young Stanley, not only for the sake of his parents, but also for his own; for the bright rosy face and frank manner of the lad inclined all who met him to feel kindly towards him.

It was with no small regret that Captain Guise, on the very first evening when the officers all dined together, saw that young face flushed not with health, but with wine, and that frank manner become more boisterous than it had been earlier in the day. Not that Norman Stanley could have been called drunk, but he had taken a little more wine than was good for him to take; and his friend knew but too well in what such a beginning of life in India was likely to end.

The captain was a good and sensible man, and he could not see his young relative led into folly and sin without warning him of the danger into which he was heedlessly running. Captain Guise, on the following day, therefore, visited Norman in his tent, and tried to put him on his guard against too close friendship with Dugsley and Danes, and to show him the peril of being drawn by little and little into intemperate habits.

Norman Stanley, who thought himself quite a man because he could wear a uniform and give commands to gray-bearded soldiers, was a little hurt at any one's thinking of troubling him with advice. Captain Guise had, however, spoken so kindly that the lad could not take real offence at his words, but only tried to show his friend that his warning was not at all needed.

"I shall never disgrace myself by becoming a drunkard, you may be certain of that," said the youth; "no one despises a sot more than I do, and I shall never be one. As for taking an extra glass of champagne after a long day's shooting, that is quite a different thing, and nobody can object to it."

"But the extra glass, Norman, is often like the thin point of the wedge," said the captain; "it is followed by another and another, till a ruinous habit may be formed."

"I tell you that I shall never get into habits of drinking," interrupted young Stanley. Then, as he took up his gun to go out shooting, the cornet uttered the words with which this little story commences.

Captain Guise did not feel satisfied. He saw that his young friend was relying on the strength of his own resolutions, and in so doing was leaning on a reed. He could not, however, say anything more just then, and Norman Stanley started a new subject to give a turn to the conversation.

"By the by, Captain Guise, I've not shown you the prize which I captured yesterday. As Dugsley and I were beating about in the jungle, what should we light upon but a tiger-cub—a real little beauty, pretty and playful as a young kitten."

"What did you make of it?" asked the captain.

"Oh, I've tethered it to the tree yonder," said Norman, pointing to one not a hundred yards distant. "By good luck, I had a dog's chain and collar which fitted the little creature exactly. I mean to try if I can't rear it, and keep a tiger-cub as a pet."

"A tiger-cub is rather a dangerous pet, I should say," observed Captain Guise, with a smile.

"Oh, not a bit of it!" cried Norman lightly. "The little brute has no fangs to bite with, and if it had, the chain is quite strong enough to—"

The sentence was never finished, for while the last word was yet on the smiling lips of the youth, the sudden sound of a savage roar from a neighbouring thicket made him start, turn pale, and grasp his gun more firmly. Forth from the shade of the bushes sprang a large tigress. In a minute, with a few bounds, she had cleared the space between herself and her cub! Snap went the chain, as the strong wild beast caught up her little one in her mouth; and before either Norman or the captain (who had snatched up a second gun) had time to take aim, the tigress was off again, bearing away her rescued cub to the jungle!

"That was a sight worth seeing!" exclaimed Captain Guise. "I never beheld a more splendid creature in all my life!"

Norman, who was very young, and quite unaccustomed to having a tiger so near him with no iron cage between them, looked as though he had not enjoyed the sight at all. "I should not care to meet that splendid creature alone in the jungle," he observed. "Did you not notice how the iron chain snapped like a thread at the jerk which she gave it?"

"Yes," replied Captain Guise, as he turned back into the tent; "what will hold in the cub, is as a spider's web to the full-grown wild beast. You had, as I told you, a dangerous pet, Norman Stanley. You might play for a while with the young creature, but claws will lengthen and fangs will grow. And," the captain added more gravely, "this is like some other things which are at first but a source of amusement, but which are too likely to become at last a source of destruction."

Norman Stanley's cheek reddened, for he felt that it was not merely of a tiger's cub that his friend was speaking. Evil habits, which at first seem so weak that we believe that we can hold them in by a mere effort of will, grow fearfully strong by indulgence. Many a wretched drunkard has begun by what he called merely a little harmless mirth, but has found at last that he has been fostering something more dangerous still than a tiger's cub. His good resolutions have snapped; he has been carried away by a terrible force with which he has not had the strength to grapple; and so has proved the truth of the captain's words, that what is at first but a source of amusement may be at last a source of destruction.

IV. NOT ONE TOO MANY.

"NO, neighbour, you've not one too many," observed Bridget Macbride, as she stood in the doorway of the cottage of Janet Maclean, knitting coarse gray socks as fast as her fingers could go.

"It's easy enough for you to say so," replied Janet, who was engaged in ironing out a shirt, and who seemed to be too busy even to look up as she spoke—"it's easy enough for you to say so, Bridget Macbride. You've never had but three bairns [children] in your life, and your husband, he gets good wages. You'd sing to a different tune, I take it, if you'd nine bairns, as I ha'e, the oldest not twelve years old—nine to feed, to clothe, and to house, and to toil and moil for, and your goodman getting but seven shillings a-week, though he's after the sheep from morning till night!" Mrs. Maclean had been getting quite red in the face as she spoke, but that might have been from stooping over her ironing work.

"Still, children are blessings,—at least, I always thought mine so," observed Bridget Macbride.

"Blessings; yes, to be sure!" cried Janet. "I thought so too, till there were so many of them that we had to pack in the cottage like herrings in a barrel."

Janet was now ironing out a sleeve, and required to go rather more gently on with her work. "I'm sure nae folk welcomed little ones more than Tam and I did the four first wee bairns, though many a broken night's rest we had wi' poor Jeanie,—and I shall never forget the time when the measles was in our cottage, and every ane o' the four had it! Yes," the mother went on, "four we could manage pretty well, with a wee bit o' pinching and scraping; but then came twins; and then little Davie; and afore he could toddle alane, twins again!" And Janet banged down her iron on its stand, as if two sets of twins were too much for the patience of any parent to endure.

"You must have a struggle to keep them all," observed Bridget Macbride.

"Struggle! I should say so!" cried Janet, looking more flushed and angry than ever. "We never could have got on at all, had I not taken in washing and ironing; and it's no such easy matter, I can tell you, to wash and iron line things for the gentry with twin-babies a-wanting you to look after them every hour in the twenty-four!"

It seemed as if the babies had heard themselves mentioned, for from the rude cradle by the fire came a squall, first from one child, and then from both, and poor Janet was several minutes before she could get either of them quiet again.

"You've a busy life of it indeed," observed Bridget, as soon as the weary mother was able once more to take up her iron.

"'Deed you may say so," replied Janet sharply, plying her iron faster, as if to make up for lost time. "And for all my working, and Tam's, we can scarce get enough of bread or porridge to fill nine hungry mouths; and as for meat, we don't see it for weeks and weeks—not so much as a slice of bacon! Then there's the schooling of the twa eldest bairns to be paid for, as Tam and I won't ha'e them grow up like heathen savages; and we'll hae them gae decent too, not in rags and barefooted, like beggars. And I should like to know—" Janet was ironing fast, but talking faster—"I should like to know how shoon [shoes] and sarks [shirts], and a plaidie for this ane, and a bonnet for anither, and breakfasts o' bannocks, and porridge for supper, are a' to come out of that wash-tub?"

"And yet," observed Bridget Macbride, "hard as you have to work for your children, I don't believe that you would willingly part with one of them, neighbour."

Even as she spoke, there was a distressful cry of "Mither! Mither!" as Janet's two eldest children burst suddenly into the cottage, looking unhappy and frightened.

"What ails the bairns?" asked Janet anxiously, turning round at the cry.

"O mither, we've lost wee Davie; we can't find him nowhere in the wood, and we be afeard as he may have fallen over the cliff."

"Davie! My bairn! My darling!" exclaimed poor Janet, forgetting in a moment all her toils and troubles in one terrible fear. Down went the iron on the table, and without waiting to put on bonnet or shawl, the fond mother rushed out of the cottage, to go and search for her child. Bridget had spoken the truth; Janet might complain of the trouble brought by a large family, but she could not bear to part with one out of her flock. If Davie had been the only child of a rich mother, instead of the seventh child of a poor one, he could not have been sought with more eager anxiety, more tender, self-forgetting love.

Followed by several of her children, but outstripping them all in her haste, Janet was soon at the edge of the wood. "Davie! Davie! My bairn! My bairn!" resounded through the forest. The mother's cry was answered by a distant whoop and halloo;—Janet knew the voice of her husband, and her heart took courage from the sound. But her hope was changed into delight, when she caught a glimpse between the trees of the shepherd coming towards her, with her little yellow-haired laddie Davie perched on his broad shoulders, grasping with one hand his father's rough locks, and with the other a bannock, which he was nibbling at as he rode.

"The Lord be praised!" cried poor Janet, and rushing forward she caught the child from her husband, pressed Davie closely to her heart, and burst into a flood of grateful tears.

"You must look a bit better after your stray lamb, Janet," said Tam with a good-humoured smile. "I was just crossing the wood when Trusty set up a barking which made me go out o' my way just to see if he had found a rabbit, or started a black-cock. There was our wean [child] sitting much at his ease, munching a bannock, as contented and happy as if he'd been a duke eating venison out of a golden dish. But you mustna let the wee bairn wander about by himself, for if he'd gaen over the cliff, we'd never hae heard the voice o' our lammie again."

Very joyful and very thankful was Janet Maclean, as, with her boy in her arms, she returned to her cottage. Bridget had remained there to take care of the twins during the absence of their mother.

Mrs. Macbride received her neighbour with a smile, and the words, "Didna I say, Janet, that ye'd not one too many, nor would willingly part wi' a single bairn out o' your nine?"

"The Lord forgi'e my thankless heart!" said poor Janet, and she fondly kissed her boy. "We ne'er are grateful enough for our blessings until we are like to lose them."

Then putting the little child down on the brick floor, with fresh courage and industry the mother returned to her ironing again.

May we not hope that all Janet's toil and hard work for her children had one day a rich reward? May we not hope that not one out of the nine, when old enough and strong enough to labour for her who had laboured so hard for them, but did his best to repay her care and her love? How large is a parent's heart, that opens wide and wider to take in all the children of her family, however numerous those children may be! Though each new babe adds to poor parents' toils, and takes from their comforts, still the kind father and the fond mother, as they look round their home circle of rosy faces, can not only say but feel, "There is not one too many."

V. THE IRON RING.

CHANG WANG was a Chinaman, and was reputed to be one of the shrewdest dealers in the Flowery Land. If making money fast be the test of cleverness, there was not a merchant in the province of Kwang Tung who had earned a better right to be called clever. Who owned so many fields of the tea-plant, who shipped so many bales of its leaves to the little Island in the west, as did Chang Wang? It was whispered, indeed, that many of the bales contained green tea made by chopping up spoilt black tea-leaves, and colouring them with copper—a process likely to turn them into a mild kind of poison; but if the unwholesome trash found purchasers, Chang Wang never troubled himself with the thought whether any one might suffer in health from drinking his tea. So long as the dealer made money, he was content; and plenty of money he made.

But knowing how to make money is quite a different thing from knowing how to enjoy it. With all his ill-gotten gains, Chang Wang was a miserable man, for he had no heart to spend his silver pieces, even on his own comfort. The rich dealer lived in a hut which one of his own labourers might have despised; he dressed as a poor Tartar shepherd might have dressed when driving his flock. Chang Wang grudged himself even a hat to keep off the rays of the sun. Men laughed, and said that he would have cut off his own pigtail of plaited hair, if he could have sold it for the price of a dinner! Chang Wang was, in fact, a miser, and was rather proud than ashamed of the hateful vice of avarice.

Chang Wang had to make a journey to Macao, down the great river Yang-se-kiang, for purposes of trade. The question with the Chinaman now was in what way he should travel.

"Shall I hire a palanquin?" thought Chang Wang, stroking his thin moustaches. "No, a palanquin would cost too much money. Shall I take my passage in a trading vessel?"

The rich trader shook his head, and the pigtail behind it,—such a passage would have to be paid for.

"I know what I'll do," said the miser to himself; "I'll ask my uncle Fing Fang to take me in his fishing boat down the great river. It is true that it will make my journey a long one, but then I shall make it for nothing. I'll go to the fisherman Fing Fang, and settle the matter at once."

The business was soon arranged, for Fing Fang would not refuse his rich nephew a seat in his boat. But he, like every one else, was disgusted at Chang Wang's meanness; and as soon as the dealer had left his hovel, thus spoke Fing Fang to his sons, Ko and Jung,—

"Here's a fellow who has scraped up money enough to build a second porcelain tower, and he comes here to beg a free passage in a fishing boat from an uncle whom he has never so much as asked to share a dish of his birds' nests soup!"

"Birds' nests soup, indeed!" exclaimed Ko. "Why, Chang Wang never indulges in luxuries such as that. If dogs' flesh * were not so cheap, he'd grudge himself the paw of a roasted puppy!"

"And what will Chang Wang make of all his money at last?" said Fing Fang more gravely. "He cannot carry it away with him when he dies!"

"Oh, he's gathering it up for some one who will know how to spend it," laughed Jung. "Chang Wang is merely fishing for others; what he gathers, they will enjoy!"

It was a bright, pleasant day when Chang Wang stepped into the boat of his uncle, to drop slowly down the great Yang-se-kiang. Many a civil word he said to Fing Fang and his sons, for civil words cost nothing. Chang Wang sat in the boat twisting the ends of his long moustaches, and thinking how much money each row of plants in his tea-fields might bring him. Presently, having finished his calculations, the miser turned to watch his relations, who were pursuing their fishing occupation in the way peculiar to China. Instead of rods, lines, or nets, the Fing Fang family was provided with trained cormorants, which are a kind of bird with a long neck, large appetite, and a particular fancy for fish.

It was curious to watch a bird diving down in the sunny water, and then suddenly come up again with a struggling fish in his bill. The fish was, however, always taken away from the cormorant, and thrown by one of the Fing Fangs into a well at the bottom of the boat.

* Noted Chinese dishes.

"Cousin Ko," said the miser, leaning forward to speak, "how is it that your clever cormorants never devour the fish they catch?"

"Cousin Chang Wang," replied the young man, "dost thou not see that each bird has an iron ring round his neck, so that he cannot swallow? He only fishes for others."

"Methinks the cormorant has a hard life of it," observed the miser, smiling. "He must wish his iron ring at the bottom of the Yang-se-kiang."

Fing Fang, who had just let loose two young cormorants from the boat, turned round, and from his narrow slits of Chinese eyes looked keenly upon his nephew.

"Didst thou ever hear of a creature," said he, "that puts an iron ring around his own neck?"

"There is no such creature in all the land that the Great Wall borders," replied Chang Wang.

Fing Fang solemnly shook the pigtail which hung down his back. Like many of the Chinese, he had read a great deal, and was a kind of philosopher in his way.

"Nephew Chang Wang," he observed, "I know of a creature (and he is not far off at this moment) who is always fishing for gain—constantly catching, but never enjoying. Avarice—the love of hoarding—is the iron ring round his neck; and so long as it stays there, he is much like one of our trained cormorants—he may be clever, active, successful, but he is only fishing for others."

I leave my readers to guess whether the sharp dealer understood his uncle's meaning, or whether Chuang Wang resolved in future not only to catch, but to enjoy. Fing Fang's moral might be good enough for a Chinese heathen, but it does not go nearly far enough for an English Christian. If a miser is like a cormorant with an iron ring round his neck, the man or the child who lives for his own pleasure only, what is he but a greedy cormorant without the iron ring? Who would wish to resemble a cormorant at all? The bird knows the enjoyment of getting; let us prize the richer enjoyment of giving. Let me close with an English proverb, which I prefer to the Chinaman's parable,—"Charity is the truest epicure; for she eats with many mouths."

VI. THE ILL WIND.

"IT'S an ill wind that blaws naebody good, Master Harry—we maun say that," observed old Ailsie, Mrs. Delmar's Scotch nurse, as she went to close the window, through which rushed in the furious blast; "but I hae a dear laddie at sea, and when I hear the wind howl like that, I think—"

"Oh, shut the window, nurse! Quick, quick! Or we'll have the casement blown in!" cried Nina. "Did you ever hear such a gust!"

Ailsie shut the window, but not in time to prevent some pictures, which the little lady had been sorting, from being scattered in every direction over the room.

"Our fine larch has been blown down on the lawn," cried Harry, who had sauntered up to the window.

"Oh, what a pity!" exclaimed his sister, as she went down on her knees to pick up the pictures. "Our beauty larch, that was planted only this spring, and that looked so lovely with its tassels of green! To think of the dreadful wind rooting up that! I'm sure that this at least is an ill wind, that blows nobody good."

"You should see the mischief it has done in the wood," observed Harry; "snapping off great branches as if they were twigs. The whole path through the wood is strewn with the boughs and the leaves."

"I can't bear the fierce wind," exclaimed Nina. "When I was out half an hour ago, I thought it would have blown me away. I really could scarcely keep my feet."

"I could not keep my cap," laughed Harry. "Off it scudded, whirling round and round right into the river, where I could watch it floating for ever so long. I shall never get it again."

"Mischievous, horrid wind!" cried Nina, who had just picked up the last of her pictures.

"Oh, missie, ye maunna speak against the wind—for ye ken who sends it," observed the old nurse. "It has its work to do, as we hae ours. Depend on't, the proverb is true, 'It's an ill wind that blaws naebody good.'"

"There's no sense in that proverb," said Harry, bluntly. "This wind does nothing but harm. It has snapped off the head of mamma's beautiful favourite flower—"

"And smashed panes in her greenhouse," added Nina.

It was indeed a furious wind that was blowing that evening, and as the night came on it seemed to increase. It rattled the shutters, it shrieked in the chimneys, it tore off some of the slates, and kept the children awake with its howling. The storm lulled, however, before the morning broke; and when the sun had risen, all was bright, calm, and serene.

"What a lovely morning after such a stormy night!" cried Nina, as with her brother Harry she rambled in the green wood, while old Ailsie followed behind them. "I never felt the air more sweet and fresh, and it seemed so heavy yesterday morning."

"Ay, ay, the wind cleared the air," observed Ailsie. "It's an ill wind that blaws naebody good."

"But think of your poor son at sea," observed Harry.

"I was just thinking o' him when I spake, Master Harry. I was thinking that maybe that verra wind was filling the sails o' his ship, and blawing him hame all the faster, to cheer the eyes o' his mither. It is sure to be in the right quarter for some one, let it blaw from north, south, east, or west."

"Why, there's little Ruth Laurie just before us," cried Harry, as he turned a bend in the woodland path. "What a great bundle of fagots she is carrying bravely on her little back!"

"Let's ask her after her sick mother," said Nina, running up to the orphan child, who was well-known to the Delmars.

Ruth dwelt with her mother in a very small cottage near the wood; and the children were allowed to visit the widow in her poor but respectable home.

"Blessings on the wee barefooted lassie!" exclaimed Ailsie. "I'll be bound, she's been up with the lark, to gather up the broken branches which the wind has stripped from the trees."

"That's a heavy bundle for you to carry, Ruth!" said Harry. "It is almost as big as yourself."

"I shouldn't mind carrying it were it twice as heavy and big," cried the peasant child, looking up with a bright, happy smile. "Coals be terrible dear, and we've not a stick of wood left in the shed; and mother, she gets so chilly of an evening. There's nothing she likes so well as a hot cup of tea and a good warm fire; your dear mamma gives us the tea, and you see I've the wood for boiling the water. Won't mother be glad when she sees my big fagots; and wasn't I pleased when I heard the wind blowing last night, for I knew I should find branches strewn about in the morning!"

"Ah," cried Harry, "that reminds me of the proverb: 'Tis an ill wind that blows nobody good."

"Harry," whispered Nina to her brother, "don't you think that you and I might help Ruth to fill her poor mother's little wood-shed?"

"What! Pick up sticks, and carry them in fagots on our backs? How funny that would look!" exclaimed Harry.

"We should be doing some good," replied Nina. "Don't you remember that nurse said that the wind has its work to do, as we have ours? If it's an ill wind that does nobody good, it must be an ill child that does good to no one."

"That's a funny little tail that you tack on to the proverb," laughed Harry; "but I rather like the notion. The good wind blows down the branches, we good children pick up the branches; so the wind and the children between them will soon fill the widow's little shed."

Merrily and heartily Harry and Nina set about their labour of kindness; Ailsie's back was too stiff for stooping, but she helped them to tie up the fagots. And cheerfully, as the children tripped along with their burdens to the poor woman's cottage, Nina repeated her old nurse's proverb, "'Tis an ill wind that blows nobody good."

VII. THE TWO PETS.

A FABLE.

"AH! Poll! Poll!" cried the little spaniel Fidele to the new favourite of the family. "How every one likes you, and pets you!"

"No wonder," replied the parrot, cocking her head on one side with a very conceited air. "Just see how pretty I am! With your rough, hairy coat, and your turned-up nose, who would look at you beside me! Just observe my plumage of crimson and green, and the fine feather head-dress which I wear!"

"I know that you are a beauty," said Fidele, "and that I'm only an ugly little dog."

"Then how clever I am," continued Miss Parrot, after a nibble at her biscuit. "No human beings are likely to care for you, for you can't speak one word of their language."

"I wish that I could learn it," said Fidele.

"You've only to copy me." And then in her harsh grating voice the parrot cried, "What's o'clock?"

"Bow-wow!" barked Fidele.

"Do your duty!" screamed the bird.

"Bow-wow!" barked the dog.

"There's not a chance that any one will ever care for you, ugly, stupid spaniel," cried Miss Poll. "You may just creep off to your kennel, you are not fit company for a learned beauty like me."

Poor Fidele made no complaint, but he felt sad as he trotted off to his corner. Before Poll's arrival at the Hall, the spaniel had been the favourite playmate of all Mrs. Donathorn's children. They had taught him to fetch and carry, to toss up a biscuit placed on his nose and catch it cleverly in his mouth, or to jump into the water and bring a stick that had been flung to ever so great a distance.

But as soon as pretty Polly came, no one seemed to care for Fidele any more. To teach the parrot to speak was the great delight of the children. They shouted and clapped their hands when she screamed out "Pretty Poll," "What's o'clock?" or, "Do your duty." Stupid Fidele! He could not be taught to speak. Ugly Fidele! Who could for a moment compare him to a beautiful parrot. So all the kind words, and soft pats, and sweet biscuits were given to Poll. It is true that she made little Tommy once cry out with pain from a bite from her sharp beak,—and that the least thing that displeased her would make her ruffle up her feathers in a very ill-tempered way; but still she was petted and praised for her cleverness and her beauty; and she quite despised poor Fidele, who was nothing but an ugly hairy dog.

One fine summer's day, the children carried the stand of their favourite to the bank of the pretty little river which flowed through their mother's grounds. Bessy and Jamie amused themselves by feeding and chatting with the parrot, while little Tommy gathered daisies and buttercups, or rolled about on the grass. No one cared for Fidele; no one noticed what he was doing.

Presently, Bessy and Jamie were startled by a scream, and then a sudden splashing noise in the water. Poor little Tommy, eager to pull some blue forget-me-nots which grew quite close to the brink, had overbalanced himself and tumbled right into the stream. Oh, what was the terror of the children when they heard the splash, and saw the wide circles on the water where their poor little brother was sinking.

"Do your duty!" screamed the parrot, merely talking by rote, and not caring a feather for the danger of the child, or the distress of his brother and sister.

At that moment, there was heard another splash in the water, and then the brown nose and hairy back of Fidele were seen in the stream, as the little dog swam with all his might to save the drowning child. He caught little Tommy by his clothes; he pulled—he tugged—he dragged him towards the shore, just within reach of the eagerly stretched-out hands of Jamie.

"Oh, he is saved! He is saved!" cried Bessy, as Tommy was dragged out of the river, dripping, choking, spluttering, crying, but not seriously hurt. He was instantly carried back to the house, undressed, and put into a warm bed; and the little one was soon none the worse for his terrible ducking and fright.

"Oh, you dear—you darling dog!" cried Bessy, as she caught up Fidele, all wet as he was, and hugged him with grateful affection. "I will always love you, and care for you, for you were a true friend in need."

"Pretty Poll!" screamed the parrot, who did not like any one to be noticed but herself.

"Fidele is better than pretty; he is brave, and useful, and good," cried Bessy.

"Do your duty!" screamed out Miss Poll.

"Ah! Poll, Poll, it is one thing to prate about duty, and another thing to do it," said Bessy. "Fine words are good, to be sure, but fine acts are a great deal better."

MORAL.

Beauty and cleverness may win much notice for a time; but it is he who is faithful, good, and true, who is valued and loved at the end.

VIII. THE BOY AND THE BIRD'S NEST.

"MARY, my love, all is ready; we must not be late for the train," said Mr. Miles, as, in his travelling dress, he entered the room where sat his pale, weeping wife, ready to start on the long, long journey, which would only end in India.

The gentleman looked flushed and excited; it was a painful moment for him, for he had to part from his sister, and the one little boy whom he was leaving under her care. But Mr. Miles' chief anxiety was for his wife; for the trial, which was bitter to him, was almost heart-breaking to her.

The carriage was at the door, all packed, the last bandbox and shawl had been put in; Eddy could hear the sound of the horses pawing the ground in their impatience to start. But the clinging arms of his mother were round him,—she held him close in her embrace, as if she would press him into her heart, and the ruddy cheeks of the boy were wet with her falling tears.

"O Eddy—my child—God bless you!" she could hardly speak through her sobs.

"My love, we must not prolong this," said the husband, gently trying to draw her away. "Good-bye, Lucy,—good-bye, my boy,—you shall hear from us both from Southampton."

The father embraced his sister and his son, and then hurried his wife to the door.

Eddy rushed after them through the hall, on to the steps, and Mrs. Miles, before entering the carriage, turned again to take her only son into her fond arms once more.

Never could Eddy forget that embrace,—the fervent pressure of the lips, the heaving of his mother's bosom, the sound of his mother's sobs. Light-hearted boy as he was, Eddy never had realized what parting was till that time, though he had watched the preparations made for the voyage for weeks,—the packing of these big black boxes that had almost blocked up the hall. Now he felt in a dream as he stood on the steps, and through tear-dimmed eyes saw the carriage driven off which held those who loved him so dearly. He caught a glimpse of his mother bending forward to have a last look of her boy, before a turn in the road hid the carriage from view; and Eddy knew that long, long years must pass before he should see that sweet face again.

"Don't grieve so, dear Eddy," said Aunt Lucy, kindly laying her hand on his shoulder; "you and I must comfort each other."

But at that bitter moment, Eddy was little disposed either to comfort any one or to receive comfort himself. His heart seemed rising into his throat; he could not utter a word. He rushed away into the woods behind the house, with a longing to be quite alone. He could scarcely think of anything but his mother; and the poor boy spent nearly an hour under a tree, recalling her looks, her parting words, and grieving over the recollection of how often his temper and his pride had given her sorrow. He felt, in the words of the touching lament,—

"And now I recollect with pain How many times I grieved her sore; Oh, if she would but come again, I think I would do so no more!"

"How I would watch her gentle eye! 'Twould be my joy to do her will; And she should never have to sigh Again for my behaving ill!"

But boys of eight years of age are seldom long unhappy. Before an hour had passed, Eddy's thoughts were turned from the parting by his chancing to glance upwards into the tree whose long green branches waved above him. Eddy espied there a pretty little nest, almost hidden by the foliage. Up jumped Eddy, eager for the prize; and in another minute, he was climbing the tree like a squirrel. Soon, he grasped and safely brought down the nest, in which, he found to his joy, three beautiful eggs.

"Ah! I'll take them home to—" Eddy stopped short; the word "mother" had been on his lips; it gave a pang to the boy to remember that the presence of his gentle mother no longer brightened that home,—that she already was far, far away. Eddy seated himself on a rough bench, and put down the nest by his side; he had less pleasure in his prize since he could not show it to her whom he loved.

While Eddy sat thinking of his parent, as he had last seen her, with her eyes red and swollen with weeping, his attention was attracted by a loud, pitiful chirping, which sounded quite near. Though the voice was only the voice of a bird, it expressed such anxious distress, that Eddy instantly guessed that it came from the poor little mother whose nest he had carried away. Ah! what pains she had taken to form that delicate nest!—how often must her wing have been wearied as she flew to and fro on her labour of love! All her little home and all her fond hopes had been torn from her at once, to give a little amusement to a careless but not heartless boy.

No; Eddy was not heartless. He was too full of his own mother's sorrow when parting from her loved child to have no pity for the poor little bird, chirping and fluttering over the treasure which she had lost.

"How selfish I have been! How cruel!" cried Eddy, jumping up from his seat. "Never fear, little bird! I will not break up your home; I will not rob you of your young. I never will give any mother the sorrow felt by my darling mamma."

Gently, he took up the nest. It was no easy matter to climb the tree again with it in his hand; but Eddy never stopped until he had replaced the nest in its own snug place, wedged in the fork of a branch. Eddy's heart felt lighter when he clambered down again to his seat, and heard the joyful twitter of the little mother, perched on a branch of a tree.

And from that day, it was Eddy's delight to take a daily ramble to that quiet part of the wood, and have a peep at the nest, half hidden in its bower of leaves. He knew when the small birds were hatched; he watched the happy mother when she fed her little brood; he looked on when she taught her nestlings to take their first airy flight. This gave him more enjoyment than the possession of fifty eggs could have done. Never did Eddy regret that he had showed mercy and kindness, and denied himself a pleasure to save another a pang.

IX. THE ENGLISH GIRL AND HER AYAH.

A LITTLE English girl in India was one day playing outside her father's tent, near the edge of a jungle. Her attention was attracted by a beautiful little fawn, that seemed too young to run about, and which stood timidly gazing at the child with its soft dark eyes. The girl advanced towards it; but the fawn started back with a frightened look and fled. The child gave chase; but the fawn was soon hid among the tall reeds and grass of the jungle.

When the girl's ayah (nurse) missed her charge, she quickly hurried after her. But so eager had the child been in pursuit of the fawn, that she was some distance from the tents before the ayah overtook her. Catching up the girl in her arms, she attempted to return; but the vegetation around grew so high that she could scarcely see two yards before her. She walked some steps with the little girl in her arms, then stopped, and looked round with a frightened air.

"We are lost!" cried the poor Hindoo. "Lost in the dreadful jungle!"

"Do not be so frightened, Motee," said the fair-haired English girl; "God can save us, and show us the way back."

The little child could feel as the poor Hindoo could not, that even in that lonely jungle a great and loving Friend was beside her!

Again, the ayah tried to find her way; again she paused in alarm. What was that dreadful sound like a growl that startled her, and made her sink on her knees in terror, clasping the little girl all the closer in her arms?

Both turned to gaze in the direction from which that dreadful sound had proceeded. What was their horror on beholding the striped head of a Bengal tiger above the waving grass! The ayah uttered a terrified scream, and the little girl a cry to God to save her. It seemed like the instant answer to that cry when the sharp report of a rifle rang through the thicket, quickly succeeded by a second, and the tiger, mortally wounded, lay rolling and struggling on the earth.

Edith—for that was the girl's name—saw nothing of what followed. Senseless with terror, she lay in the arms of her trembling ayah.

It was her father whom Providence had sent to the rescue. Lifting his little girl in his arms, he bore her back to the tent, leaving his servants, who had followed in his steps, to bring in the dead tiger. It was some time before the little girl recovered her senses, and then an attack of fever ensued.

Her mother nursed her with fondest care; and with scarcely less tenderness and love, the faithful ayah tended the child. The poor Hindoo would have given her life to save that of her little charge.

On the third night after that terrible adventure in the woods came the crisis of the fever. The girl's mother, worn out by two sleepless nights, had been persuaded to go to rest and let Motee take her turn of watching beside the child. The tent was nearly dark—but one light burned within it—Edith lay in shadow—the ayah could not see her face—a terror came over the Hindoo—all was so still, she could not hear any breathing—could the child be dead! The ayah, during two anxious days, had prayed to all the false gods that she could think of to make Missee Edith well,—but the fever had not decreased. Now, in the silence of the night, poor Motee Ayah bethought her of the English girl's words in the jungle. Little Edith had said that the Lord could save them—and had He not saved from the jaws of the savage tiger? Could He not help them now? The Hindoo knelt beside the charpoy (pallet) on which lay the fair-haired child, put her brown palms together, bowed her head, and for the first time in her life breathed a prayer to the Christian's God: "Lord Jesus, save Missee Baba!"

"O Motee! Motee!" cried little Edith, starting up front her pillow with a cry of delight, and flinging her white arms round the neck of the astonished Hindoo. "The Lord has made you love Him! And oh, how I love you, Motee!—more than ever I did before!" The curly head nestled on the bosom of the ayah, and her dark skin was wet with the little child's tears of joy.

Edith, a few minutes before, had awaked refreshed from a long sleep, during which her fever had passed away. From that hour, her recovery was speedy; and before many days were over, the child was again sporting about in innocent glee. From that night, the ayah never prayed to an idol again. She was now willing to listen to all that was told her of a great and merciful Lord. Of the skin of the tiger that had been slain, a rug was made, which Edith called her praying-carpet. Upon this, morning and night, the English girl and her ayah knelt side by side, and offered up simple prayers to Him who had saved them from death.

X. I'LL NOT LET YOU GO.

"HE is the naughtiest child in my class. I think that I must give up trying to teach him!" sighed Miss Lee, a very sickly looking lady, as on one cold afternoon in March, she returned from the Sunday-school in which she had been for some years a teacher.

"Yes, little Seth seems as if he could neither be won by kindness, nor moved by reproof. He cares neither for smiles nor for frowns. He disturbs all the rest of the boys in my class; sets them off laughing when I most wish them all to be quiet and attentive; he teases this one, quarrels with that; never by any chance knows his verse; and meets my reproofs with only a saucy look of defiance. And this is not the worst of it," thought the weary, anxious teacher, as she leaned for some moments on a high stile, as if to gather strength before she could make the effort of climbing over it; "I cannot depend on Seth's word! I am certain that it was he who threw the orange-peel under my seat, though he boldly denies that he did so, and tries to cast the blame upon others. And this is not the first time that I have had to doubt the truthfulness of the boy. I really must turn him out of my class!"

Having made this half resolve, Miss Lee set her foot on the lowest step of the stile, but instead of crossing over, she sat down to rest on the top one, though the March wind made her shiver. The lady felt very weary and faint; and a pain in her side, from which she often suffered, was more distressing than it had ever been before.

"I am sure that my pupils would give me less trouble if they knew how tired I always am when I leave them," thought the lady; "but they are all tolerably good, except Seth. And I am unwilling to give up even little Seth, troublesome, naughty boy that he is. He lost his mother when he was a baby; and his father, the farmer, is out all day long in the fields. Seth is allowed to run wild—and this is not the boy's limit. Then Seth is so young, and so small—he is only seven years old, and he scarcely looks five; surely I ought to be able to manage and guide such a child! But my strength and vigour are gone," continued Miss Lee, still speaking to herself, and she pressed her hand to her aching side. "I am scarcely fit for the effort of teaching at all; and one wilful, troublesome, saucy child tires me out more than all the rest of the boys put together. I think that I must tell Seth Rogers to come no more to my class."

With an effort which made her bite her lip with pain, Lee managed to get over the stile, and she then slowly walked along the path over some wide grassy uplands beyond.

It was pleasant to see those green uplands, dotted with sheep, and sweet was the tinkling sound of the sheep-bell. But Miss Lee was not inclined to enjoy either sight or sound. She was tired, chilly, discouraged. She was thinking for how many years she had laboured to teach children the way to Heaven, often going to the Sunday-school when scarcely well enough to walk to it. And after all her labour and pains, the teacher was not at all sure that she had been the means of really leading one little one to the Good Shepherd.

"Is it not—must it not be by some fault of my own?" thought the poor lady, as she slowly went on her way. "I have not worked hard enough, or prayed earnestly enough for my little flock, and yet not a day passes without my remembering every one of them in my prayers. I have tried to do the best that I can; but it seems as if all my efforts had been in vain, at least as regards Seth Rogers, that naughtiest child in my class!"

The path grew steeper, and Miss Lee walked yet more slowly, often stopping to take breath, until she had passed the crest of the hill. Then the loud bleating of a sheep near the bottom of it drew the lady's attention, for it sounded like a call from a creature in distress. Miss Lee turned aside from the pathway, and went down towards the sheep, to see what was the cause of its trouble; for a rough knoll hid it from view. On passing the knoll, Miss Lee came in sight of a fleecy mother who was piteously bleating, as she bent over a rushing torrent which ran at the bottom of the hill.

The lady quickened her steps; she was sure that some poor lamb must be struggling below in the water; and though very doubtful whether she herself would have strength to lift it out, she thought that she could but try. But Miss Lee's feeble help was not needed. The next step that she took brought before her view a young shepherd lad, stretched at full length on the grass, evidently engaged in a violent effort to pull something out of the water.

"I'll not let you go, little one, I'll not let you go!" muttered the lad, whose face was flushed scarlet from stooping so low over the brink of the torrent, for he could just manage to put down his hand far enough to touch the fleece of the drowning lamb.

Miss Lee stood still for several minutes, watching with interest the efforts of the young shepherd, although she had no power to aid them. It was no easy task for the lad to get the little wanderer out of the dangerous position into which it had fallen. Thrice, the strong current seemed to bear the lamb beyond reach of the shepherd lad's grasp, thrice, he had to jump up and change his position for one further down the stream; his hands were torn with brambles; but still muttering "I'll not let you go," he only redoubled his efforts, till at length the struggling creature, trembling and dripping, was lifted out of the torrent, and given back to its bleating mother.

"You are rewarded for your patience and your kindness, my lad," said Miss Lee with a smile to the youth, who was panting after his exertions.

"Ey, ma'am; 'twas a wilful lamb, it was; but I would not let it go," said the youth, as he slowly got up from the ground, and wiped his heated brow. "If I had let it drown, I'd have had to answer for it to my master."

Miss Lee turned, and went again on her homeward way, her mind full of the little incident of the rescue of the lamb, and the words of the shepherd lad seemed to ring in her ears as she walked. "Has not the Heavenly Shepherd given me some of His lambs to tend," thus reflected the Sunday-school teacher; "and shall I forsake one of them because it has wandered farther, fallen lower, and is in more danger than the rest of my little flock? Shall not I have to answer for it to my Master? More earnest, persevering effort may be needed; I may be, as it were, torn by the brambles; my poor Seth may require more constant prayers and pains; but may grace be given me to say of him what the shepherd boy said of his charge, 'I'll not let you go, little one; I'll not let you go!'"

This was the Sunday-school teacher's resolve; but she seemed likely never to be able to carry it out, for she had scarcely reached her home when she fainted.

"No, there's no use, boys, in your coming here this morning; there's no one to hold the class; so you'd better be off till the bells ring for service."

So spake old Ridger, the clerk, on the morning of the Sunday following, as he stood outside the closed door of the room in which Miss Lee was wont to meet her young pupils.

Some of the boys looked surprised, but Sam Wright, the gardener's son, observed, "I was a'most sure as there would be no class to-day, because Miss Lee is so ill."

"Ill!" echoed several voices.

"Ay, she's been ailing this long time," replied Sam. "Father says that she's never so much as taken a turn in the garden for months, and she used to have such pleasure in the flowers."

"But she has never missed her Sunday teaching once," said one of the boys.

"No, she'd come to that, if she were able to crawl," observed Sam; "that wasn't a pleasure, but a duty."

"It might have been a pleasure too, if it had not been for some chaps," said an elder boy, glancing at Seth.

"I thought that teacher looked very pale last Sunday," observed Eli Barnes, who had been one of her most attentive pupils; "but then she had been so worried. I noticed that she twice put her hand to her side."

"It was on Friday night that she was took so bad, so very bad," said Sam. "Father was just turning into bed, when there was a rap at our door; one of the servants had come over to tell him to go off in haste for the doctor. You may guess as father was not long in getting ready, for the servant said as Miss Lee seemed to be dying. The doctor came in an hour, as fast as his horse could gallop, though 'twas raining and blowing like mad. I couldn't get to sleep till I'd heard what he said of our teacher; neither could father, when he got home all wet to the skin; he must go up to the Hall for news of the lady."

"And what did the doctor say?" asked several voices at once.

Sam Wright looked very grave as he answered, "The doctor don't much expect that she'll get over the fever."

Some of the boys uttered exclamations of regret, others sighed and said nothing. All of them turned from the closed door, feeling sorry to think that their teacher might never enter it again.

In the meantime Miss Lee was lying in bed in a darkened room, while the spring sun was shining so brightly, as if to invite all to come out and enjoy his beams. The few persons who entered that room moved about as noiselessly as if they were shadows, for the poor patient was in a burning fever, and the sound of a step, or the rustle of a dress, would have been to her most distressing. No one spoke to Miss Lee, not even to ask her how she felt, for the fever had mounted into her brain, and the sufferer knew nothing of what was passing around her.

The teacher's mind was, however, still working, and even in delirium, she showed what had been the uppermost care on her mind. From the lips so parched and blackened by fever, words continually burst, though she who uttered them knew not what she was saying. The sick-nurse little guess why the patient grasped her own bed-clothes so tightly, and again and again cried out in a tone of distress, "I'll not let you go, little one; I'll not let you go!"

Most of the boys of the Sunday class strolled out on the uplands, to gather wild flowers, or to chat together, until it should be time for them to go into church. There was one little boy, however, who did not go with the rest, but preferred lingering alone amongst the graves in the churchyard. That boy was Seth Rogers, the naughtiest child in the Sunday class.

Old Ridger the clerk watched Seth, as the little fellow went slowly and laid himself down on the turf close to the grave of his mother. Ridger saw the child hide his face in his hands when he thought that he was out of the sight and hearing of all.

"That poor little motherless chap takes the lady's illness much to heart," said the good-natured clerk to himself. "I should not have expected it of Seth Rogers, for he has been—so my grandson tell me—the very plague of his teacher's life; and I myself have had to complain to the vicar a dozen times of his rude behaviour in church. Many a Sunday I've said, 'I'd like to give that young rogue a good thrashing, for there's nothing else as will bring him into order.' But the child seems quiet and sad enough now," added Ridger, and taking up his cane, the old clerk walked slowly up to the spot where Seth Rogers was lying on the turf, and as he did so, he heard from the boy something that sounded much like a sob.

"Come, child, you mustn't take on so," said the clerk, stooping over Seth, and gently touching his shoulder. "Miss Lee may recover, and get about again, if it be the Lord's will; and if not—"

Seth raised himself from the ground; the little fellow's cheeks were wet, and his eyes were glistening with tears.

"O Mr. Ridger, do you think she will die?" he asked in an agitated tone.

"We should all be very sorry were Miss Lee to die," was the old man's rather evasive answer.

"No one would be so sorry as I," cried the child, bursting into tears, "because—because—" Seth could not finish the sentence, his heart was too full for words.

Old Ridger seated himself on a bench, and drew the little boy close to his breast, for the clerk was a kindly man, and always felt for a child in trouble. He gently stroked Seth's shoulder, as he said, "I never thought that you loved your teacher so much more than do the rest of the boys."

"It's not that I loved her more, but that I worried her more," murmured the child, in a scarcely audible tone. "They did not plague her, and make her so tired, and bring the tears into her eyes. They did not tell her untruths." The boy was speaking rather to himself than to the clerk; Seth was thinking aloud in the spirit of those touching lines on the death of a mother,—

The old clerk rose from his seat, for the church-bells were sounding, and it was time for him to go and look out the psalms and the lessons for the day. Ridger had but one word of comfort to give the poor little boy before he left him alone.

"You know that you can pray for the lady," said he.

But could Seth Rogers pray? He never had prayed in his life, no, not even when he had been kneeling close to Miss Lee, while she besought the Lord to bless her and her little pupils. Seth had, alas! been too apt even then to stare around, perhaps trying to make others as careless and inattentive as he was himself. Seth had never once really joined in the prayer of his teacher, he had only been restless and impatient to have the praying-time over.

But when old Ridger had gone away, and the child was left for some minutes alone in the churchyard, then, for the first time, Seth Rogers really did pray. He threw himself again on the ground on which lay the shadow from the grave of his mother, and sobbed forth, "Oh, please—please don't let teacher die, until I've seen her again, and tried to make up for the past."

The little boy's prayer was answered. On the following day, the doctor told the anxious watchers in the sick-room that he hoped that the worst was over. A night of deep, quiet sleep succeeded, and on the Tuesday morning Miss Lee awoke quite free from fever, but so weak and low, that she could not turn in her bed.

From that hour, the lady's recovery was steady, though slow. It was not till the middle of April that the invalid was permitted to leave her room, and any occupation that could tire either body or mind was strictly forbidden. Miss Lee was, however, able to enjoy sitting in an easy-chair by the open window, as the days grew warm and long. Every morning, she found on the sill a few wild flowers; she did not know who had placed them there, but perhaps my readers may guess.

But Miss Lee only looked upon rest as a preparation for work; her life had not been prolonged to be spent in luxurious ease. As soon as the lady felt that a little strength was restored to her, she began thinking how she could best set about doing her heavenly Father's business.

"I have been able to take a little walk in the garden every day this week," said Miss Lee to herself one evening towards the close of May. "I think that I may take up my work again next month,—at all events, I will try." The lady opened her desk, and with her thin, wasted hand wrote a note to her Vicar to say that on Sunday week she hoped to meet her Bible-class in the schoolroom.

"It will be an effort, a very great effort," thought poor Miss Lee, as soon as she had sent off the note. "When I remember all the weariness and the worry that I had to bear through the winter, I can scarcely help hoping that Seth Rogers at least may have been withdrawn from my class. But oh, how this shows my want of faith and of love! Have I not prayed—prayed often both before and during my illness for the soul of that motherless child, and may not my poor stray lamb be given to me at last!"

The appointed Sunday arrived, and the first to meet his teacher at the door of the schoolroom was Seth. Miss Lee's first glance at the face of the boy raised her hopes that he was changed and improved; and her hopes were not to be disappointed. The prayers of teacher and pupil for each other had been abundantly blessed. Seth Rogers became the most steady and obedient boy in the class; it was he who most watched his teacher's eye, and most earnestly heeded her words. Of him, Miss Lee was wont to think as her "joy and crown of rejoicing;" for Seth was the first of her pupils whom she was permitted to look upon as the fruit of her labours of love. Often the sight of the boy recalled to the teacher's mind that day when she had seen the poor lamb saved from perishing; and a silent thanksgiving arose from her heart, "Heaven be praised, I did not let him go!"

XI. THE WHITE DOVE.

A PARABLE.